Get your news from a source that’s not owned and controlled by oligarchs.

Sign up for the free Mother Jones Daily.

“We wouldn’t have so much trouble if we weren’t so rich.” This is a common sentiment in the Democratic Republic of Congo, according to author Adam Hochschild, who returned to the war-torn nation to follow up on his 1998 bestseller King Leopold’s Ghost. (The resulting article, “Blood and Treasure,” appears in our March/April issue.) That quote, of course, is 24-carat irony, since Congo’s people are desperately poor—not in spite of, but largely because of the Pandora’s box that accompanies their nation’s fabulous resource wealth.

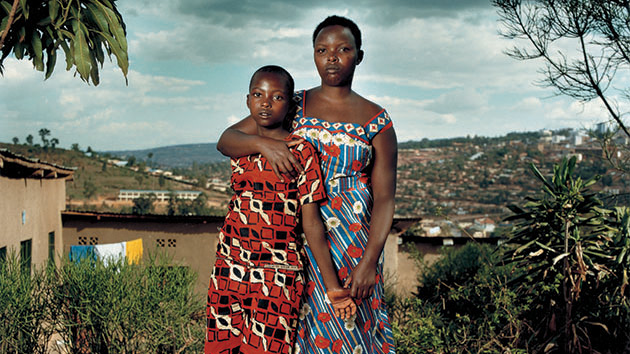

To produce this photoessay, which accompanies Hochschild’s piece in the print magazine, Marcus Bleasdale spent eight years documenting the lives and conflicts of the Congolese. His dedication has resulted in two photo books, One Hundred Years of Darkness and, out in March, Rape of a Nation—the source of the images you see here. It’s easy for Americans to remain oblivious to the troubles of people in faraway lands, but Bleasdale’s photos manage to pierce our cynical gaze. And that’s only fair, since American consumers and investors are among those who profit most from Congo’s misery—be they the Wall Street mogul who owns 12 percent of mining multinational AngloGold Ashanti, or simply everyday folks who like electronic gadgets and sparkly jewelry.

In the foreword to Rape of a Nation, bestselling novelist John le Carré sums up the country’s human hell as:

…fourteen hundred and fifty tragedies every day. It is countless more than that if you include the orphaned, the bereaved, the widowed, and all the ripples of truncated lives that spread from a single death. It is you and me and our children and our parents, if we had had the bad luck to be born into the world this book portrays. But Congo has one secret that is hard to pass on if you haven’t learned it at first hand. Look carefully and you will find a gaiety of spirit and a love of life that, even in the worst of times, leave the pampered Westerner moved and humbled beyond words.

You can also find a multimedia presentation of Bleasdale’s work at MediaStorm.

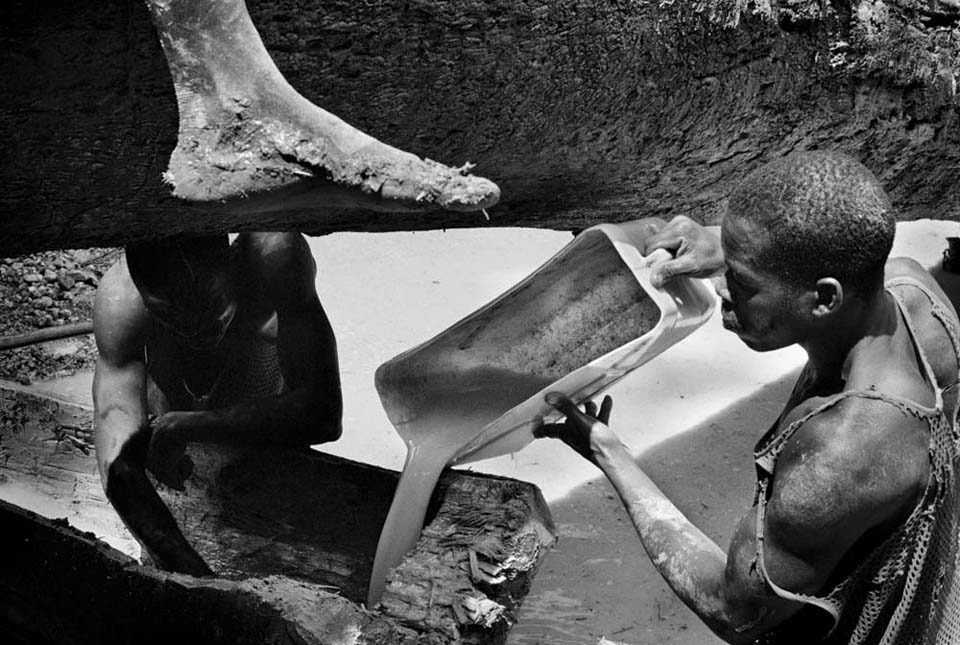

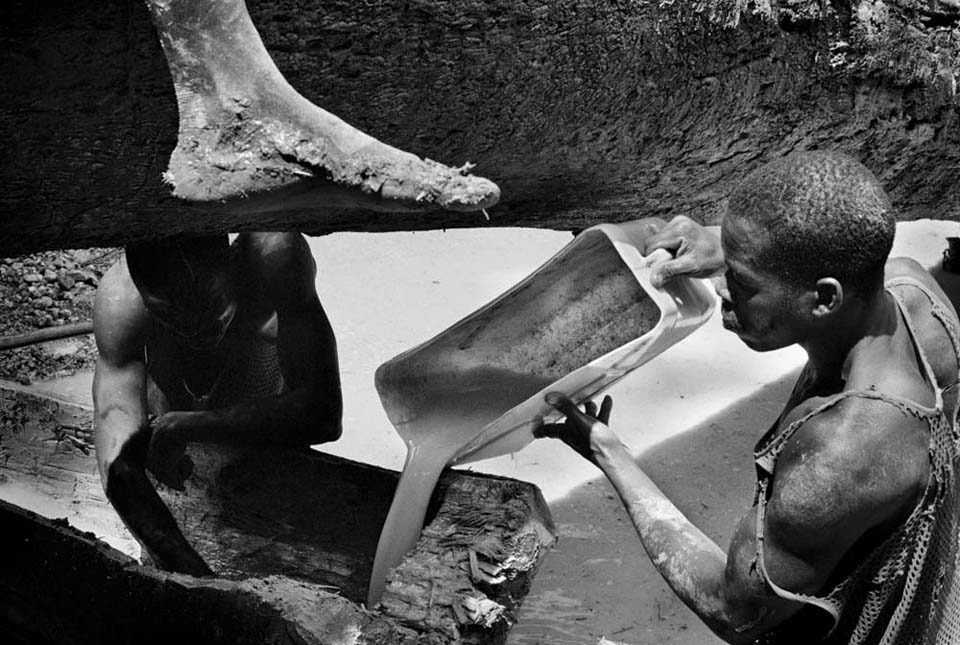

A child digs for gold in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Ituri District, where major mines are now government-run. Army officers, like the rebel officers who preceded them, profit from the operations—sometimes by directly controlling the mines and forcing soldiers or villagers to work in them. In Congo’s northeast, an estimated 70,000 to 100,000 people, including some 10,000 children, mine gold using nothing more than hand tools—and often literally by hand. But their scrappy livelihood may be coming to an end soon. Several foreign concerns, including a subsidiary of AngloGold Ashanti, the world’s third-largest gold-mining firm, recently cut deals with the Congolese government to take over the region’s lucrative mining operations.

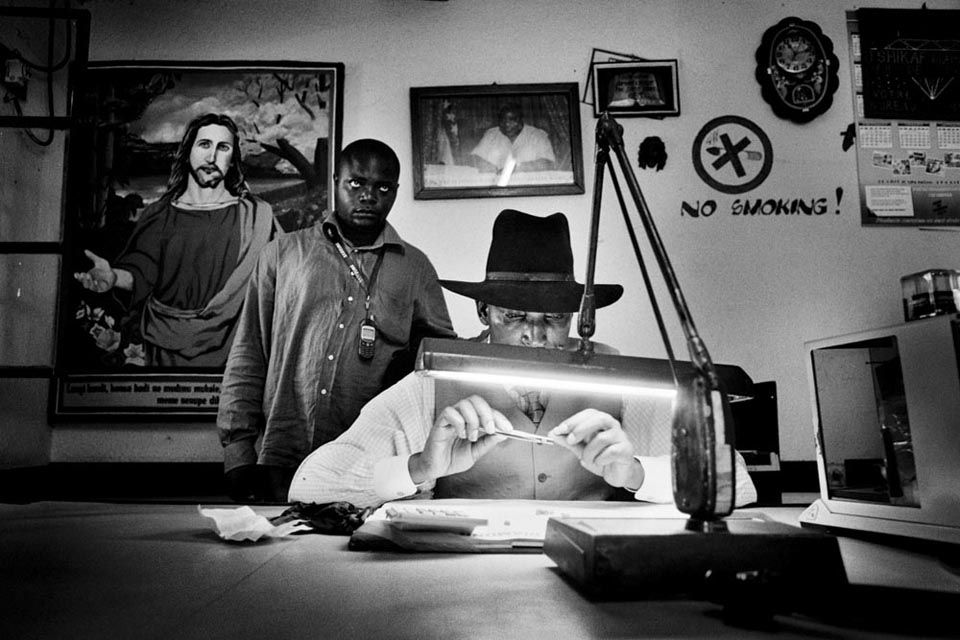

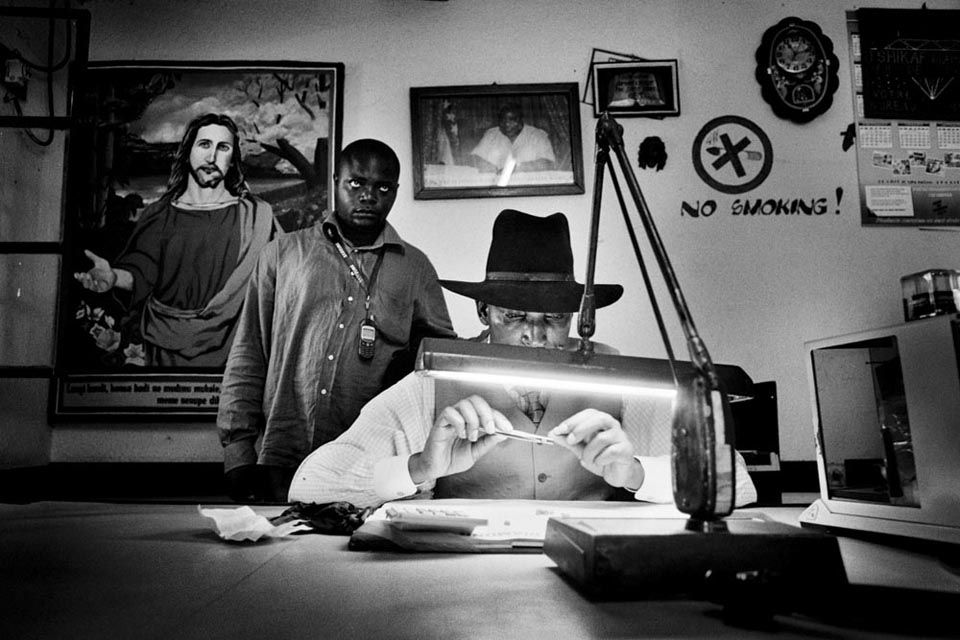

Dealers in the Congo’s mining towns buy diamonds, gold, and whatever else locals manage to wrest from the ground by hand. Above, a dealer scrutinizes gems in Mbuji Maji, the nation’s diamond hub. This city, where farming has been largely swept aside by activities related to the diamond rush, has a boomtown population of 3 million. Some dealers have even become church pastors in the hopes that miner-congregants will sell them diamonds at a discounted rate.

In Mongbwalu, where this freelance miner was photographed, the streets are bordered by open sewage ditches and lined with shops that buy gold and sell mining supplies—a raindrop-sized globule of mercury in a plastic baggie goes for about 75 cents, a shovel blade for $5. (Cut your own handle from the rainforest.) Most of these small-time prospectors are former combatants whose factions controlled the mineral-rich areas and profited from their exploitation.

Men pan for gold in the Ituri District, where the coveted metal, far more than any ideology or ethnicity, has driven more than a decade of brutal conflict. Following the 1997 death of repressive dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, fighting between shifting coalitions of militias led to the gang-rapes of tens of thousands of women and girls by government and rebel soldiers—who used rape as a tactic to terrorize and control local populations.

A man hauls ore from a hand-dug tunnel in Wasta, in the Ituri District. Freelance gold mining is uniquely treacherous, as men hack out new tunnels in abandoned, flooded underground mines with rotten roof supports. Most of the gold retrieved this way leaves the country illegally via Uganda, and only a small fraction of the proceeds will stay in Congo. Foreign mining companies also take the money and run: In neighboring Tanzania, AngloGold Ashanti mined $1.5 billion worth of gold from 2000 to 2007, but only 9 percent of that money stayed behind as taxes and royalties. In the meantime, the firm’s top shareholder—hedge fund billionaire John Paulson—lives on New York’s Upper East Side and summers in the Hamptons.

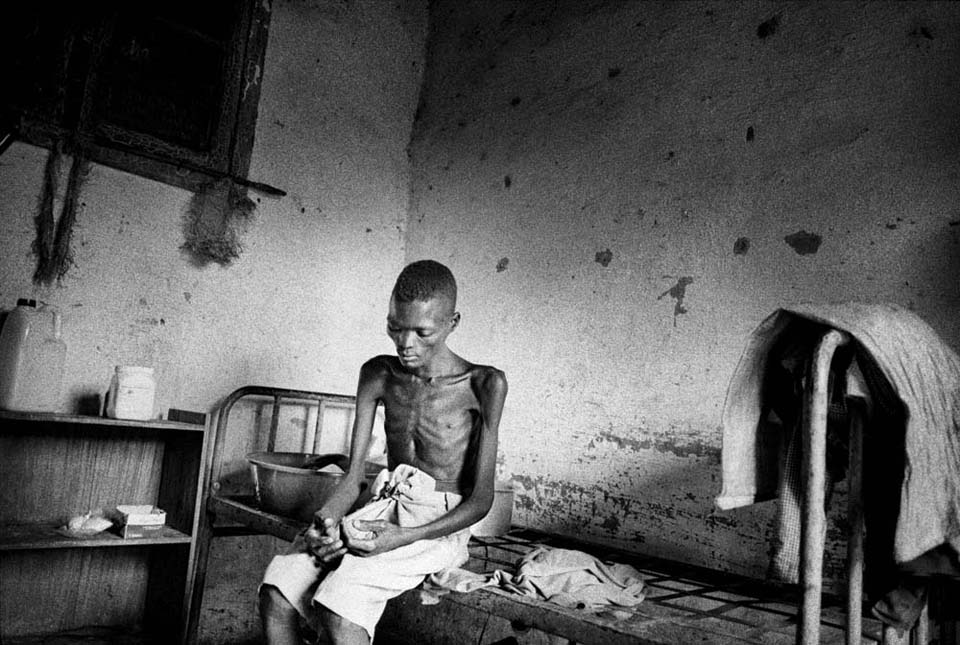

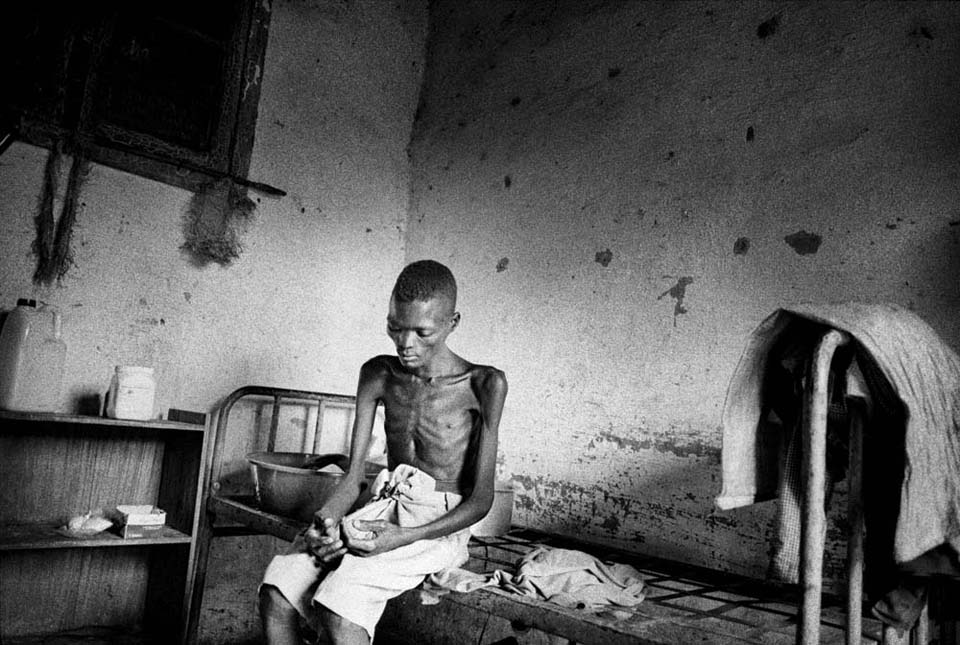

As if the work alone weren’t brutal enough, many Congolese miners find themselves stricken by illness—malaria being the biggest killer. This former miner suffers from tuberculosis and has been left to fend for himself in a sanatorium in Mongbwalu.

Refugees flee a rebel warlord’s attack in Ituri in 2003. Beyond the rapes, the resource wars have displaced more than 500,000 people in this West Virginia-sized district alone, and killed more than 60,000. More broadly, the nation’s conflict, together with lack of access to medical care, has likely claimed the lives of millions since 1998.

In Mongbwalu, family members wash the body of eight-month-old Sakura Lisi, a gold miner’s daughter who died of malaria. Congo has virtually no public health system. AngloGold Ashanti, which has spent millions of dollars prospecting in this desperately poor area—and plans to extract billions in gold—has made only small contributions to a local hospital, schools, and a soccer tournament. “Nothing has been done,” complains a local chief.

Mourners say a final prayer at the burial of Sakura Lisi, infant daughter of an artisan gold miner.

Teams pound rocks into dust in metal buckets to retrieve the flecks of gold they contain. Many miners in the Ituri District are former fighters who struggle to survive on the dollar or two worth of gold dust they scrape together each day. It’s often their only job option. “There is no work in Congo,” one miner laments.