<a href="https://www.flickr.com/photos/ari/5139354384/in/photolist-8Q9x1m-8Q6f5i-8Q6eWK-9hcBks-8Q9wGo-8Q9wf7-8Q9wTf-8Q6qfn-8Q9wWC-8Q6fec-8Q9wbU-fZQJX7-e53Pzu-e53NRG-e53Ptq-e53P8y-e53NxQ-e4Xa6n-e4XawR-e4X9Cx-5TN3-8MamdV-8MdoTS-ac1sZz-jqmrL5-deqxd3-deqxmq-deqypD-deqx13-deqxhh-deqyfT-fk222-9cDAB2-8Q4p5T-7Xggbk-5jc5jh-3X79qR-oYpneb-8Q7vZm-9aTBHr-95y3ws-a6K9iz-7rjjgm-5JKdU-ay85L-8KVf7B-eusRxZ-aJzja6-j7cXP8-5t87Pu">Steve Rhodes</a>/Flickr

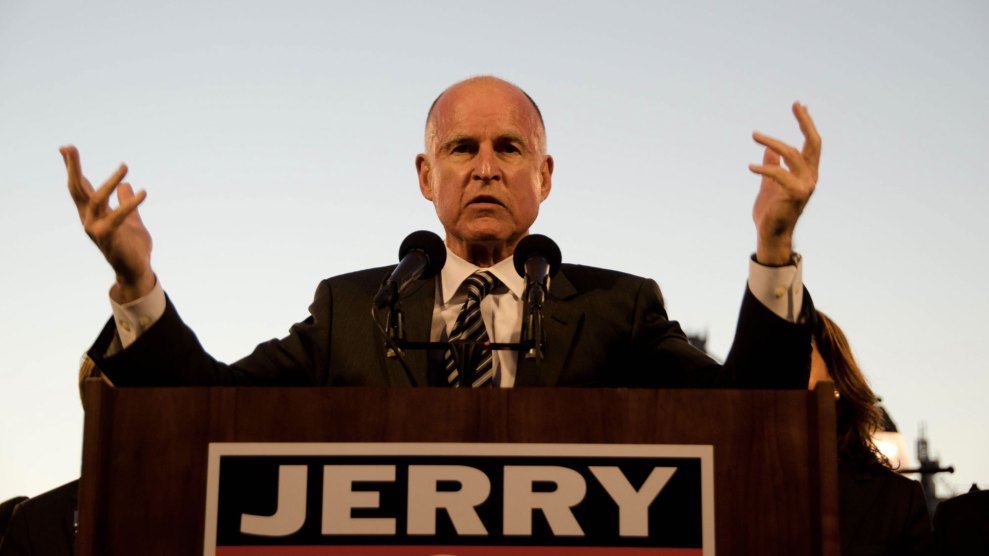

Jerry Brown is in his element. It’s 7:30 a.m., and the burgundy-and-green-carpeted ballroom of the Marriott hotel in downtown Oakland is filling up with bleary-eyed reporters, politicians, and business executives who have come to hear him deliver his first State of the City address. Dressed in a khaki suit and a vaguely clerical, banded-collar shirt, Mayor Brown makes his way down the aisle, trailed by a gaggle of TV cameramen. Everything about him, from his finishing-school posture to the way he surveys the crowd before beginning to speak, suggests he is doing something that’s as natural to him as breathing: being a politician.

Brown hasn’t always been sure that he wanted to be a politician. He has spent his career seesawing between the enthusiastic embrace and ascetic rejection of the political life. The scion of one of California’s most prominent political families, he followed in the footsteps of his father, Edmund G. “Pat” Brown, to serve two terms as governor of California, between 1974 and 1982–but spurned the ornate governor’s mansion and chauffeur-driven limousine in favor of a modest Sacramento apartment and a Plymouth sedan. He made an unsuccessful run for U.S. Senate in 1984–then left politics altogether to work with Mother Teresa in India. In 1989 he took over as chairman of the state Democratic Party–then resigned the post two years later, disgusted by the burgeoning influence of political contributions.

By 1992 he had become the Democratic Party’s Don Quixote, railing against the money-fueled political system he described as “a banquet feast of corruption” during a high-profile run for president. Two years later Brown repackaged himself as the left’s answer to Rush Limbaugh. He launched a talk-radio show that featured such guests as Noam Chomsky, Jonathan Kozol, and Helena Norberg-Hodge, with whom he discussed the “private tyrannies” of major corporations, the hidden misery of America’s permanent underclass, and the “McDonald’s-ization” of the planet.

But now, as he takes the podium to deliver his State of the City address (sponsored by the Oakland Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce), such themes seem to be the farthest thing from his mind. Instead he launches into a conventional bout of civic cheerleading, promising to make Oakland “a place that’s exciting, that’s humming” and warning against the transitory comforts of the status quo. Aware that he is addressing the leadership of the city’s business community, he promises to stand firm against those who oppose development, criticizing residents who protested the construction of a large loft-style apartment complex, and berating preservationists who have sued to save a 1920s-era building whose demolition would have made way for a new Gap store. “I’m going to tell potential supporters of these projects,” he thunders, “‘You have a friend in the mayor’s office.'”

The Chamber of Commerce has heard speeches like this before: rah-rah exhortations for a business-friendly city, rousing declarations about the progress that can be made if commerce is freed from the impediments of bureaucratic red tape and citizen skepticism. But it’s a bit startling coming from Brown, who a writer for The Nation predicted, just before last year’s election, would be “the most radical mayor in America.”

Brown certainly can claim credit for having promoted some of the most progressive policies of any contemporary politician during his terms as governor. He appointed an unprecedented number of women and minorities to high-ranking positions, halted the development of nuclear power, and enacted the nation’s first agricultural labor law. But he has always shown a deep-seated resistance to anything that smacks of ideology, and his approach to city government has turned out to be far more conservative–and pragmatic–than his radio-show colloquies and radical reputation would indicate.

“We have to stop thinking that Jerry Brown ever was a leftist–he’s a populist,” says Eugene “Gus” Newport, a former mayor of neighboring Berkeley. “I didn’t think of him as a leftist when I supported him: I thought of him as a change agent, compassionate and ethical, and I’ll take that any day.”

When Brown first announced his candidacy for Oakland mayor, political pundits wondered whether this mercurial figure could sustain an interest in the quotidian questions of municipal governance. Here was a man whose visionary impulses once earned him the nickname “Governor Moonbeam” asking to be put in charge of a city plagued by the all-too-concrete problems of late-20th-century urban disinvestment: unemployment, crime, failing schools, a declining retail base, and an expensive and perennially dissatisfied football team.

But as Brown roved the campaign trail, moving from linoleum-floored church basements to the crowded common rooms of low-income apartment complexes, he articulated a platform that could as easily have come from Los Angeles’ Richard Riordan or Chicago’s Richard Daley: Improve the schools, encourage economic development, and above all, fight crime. He may have been preaching against the government’s “phony war on drugs” at the start of the campaign, but by his inauguration he was pledging to “support every lawful action and utilize the criminal justice system to the maximum to rid our neighborhoods of criminals.”

“He talked with folks, and he listened,” explains Oakland City Councilmember John Russo. “Jerry’s actually a very good listener. He analyzes, he synthesizes, and he holds the mirror

up. And what he heard the public say is, There’s too much crime, and something has to be done about the schools. If folks were expecting that after Jerry came in we would all be eating organic vegetables and singing old folk songs, they were not reading his campaign literature.”

Brown has lived in Oakland only since 1994, but he intuitively grasps the pent-up civic pride that dwells, largely untapped, within its residents’ collective psyche. Located across the bay from Brown’s hometown of San Francisco, the 56-square-mile city of 387,000 souls encompasses tony, forested enclaves in the hills several miles east of the bayshore, and an assortment of well-integrated middle- and working-class neighborhoods in the flatlands. A fast-growing airport and a world-class shipping port are among the city’s economic engines, while several shopping districts studded with bookstores, juice bars, and upscale restaurants help belie the popular notion of Oakland as “Newark West.”

Oaklanders have long wondered why this eclectic collection of assets has never translated into a favorable national image and meaningful economic growth, and Brown’s gift for garnering media attention has convinced many of them that their time has come at last. “The euphoria and the optimism are really at an interesting stage right now,” says David Glover, a longtime observer of Oakland politics. “It’s almost like a lump in the throat.”

In the year since his election, Brown has shown skill at harnessing that euphoria and using it to power his own agenda. The day after he won every precinct in the city save two, he unleashed an army of volunteers to collect signatures for a “strong mayor” initiative that would give him a vastly broader set of powers, including the right to hire and fire city department heads. If people really wanted change, he argued, they had to allow him to exert more control over the bureaucracy.

The strong-mayor form of government had appeared on the ballot twice before, and been defeated both times. It had always been popular among working-class voters in the flatlands, but the wealthier, more conservative voters in the hills preferred to keep municipal power in the hands of the city’s professional staff. This time around, however, hills voters decided they were willing to take the risk. The measure passed by a 3-1 margin, and within a few months of taking office Brown had engineered the resignations or demotions of four department heads–including the city’s African American chief of police, who had been criticized for spending too much of the budget on officer overtime and not enough on new technology.

The purging of city staff was one of the more controversial events of Brown’s first hundred days in office, and the mayor spent several weeks besieged and berated by black ministers and politicians who wanted to see the police chief remain on the job. There was talk of a recall, or of trying to reverse the strong-mayor proposal in the next election, but Brown remained firm, accusing those who decried the change of being “tranquilized” by “the drug of gradualism.” In the end, the opposition retreated.

Brown displayed a similar implacability when he invited the Navy and the U.S. Marines to come to Oakland for 3 days of exercises designed to prepare several hundred troops for urban combat. Local peace activists saw the war games as either a hideously expensive recruitment technique or a thinly disguised dress rehearsal for the quelling of urban insurrections, and the ensuing protests included a picket of Brown’s home and a noisy takeover of his office in City Hall. Brown declared himself puzzled by all the fuss, pointing out that the military exercise would net the city several million dollars and likening the entire event to a Chinese New Year’s parade. “There seems to be serious problems on the left with finding ways to express themselves,” he remarked after the office sit-in. “I have to say, it’s more pathetic than serious.”

These kinds of remarks don’t sit well with Brown’s erstwhile supporters on the left, many of whom thought they were electing the man who used his radio show to fulminate against the “powerful propaganda and distortion” of the military-industrial complex and the “perversity” of an economy that failed to address the sufferings of the poor.

“I thought I knew who Jerry was,” sighs former Oakland City Councilmember Wilson Riles Jr., who backed Brown during his campaign. “I thought I could look at his history.”

In fact, Brown’s history is a mosaic of progressive and conservative positions, a blend that will likely persist. Though he has spoken in the past about the “absolute oppression [and] disconnection” resulting from America’s “experiment in incarceration,” Mayor Brown has shown himself a strict law-and-order man. One of his first acts as mayor was to appear at the sentencing of a notorious cocaine kingpin in order to send “a real message to drug dealers in Oakland that their time is over.” Since then he has been single-minded in his attention to the crime issue, embracing a federal program that establishes a five-year prison sentence for illegal gun possession, and backing several policies that seem modeled in part on measures that Mayor Rudolph Giuliani adopted to clean up New York City. (Among the latter: a geographically based accountability system making commanders in 15 “police service areas” responsible for reducing crime on their turf.)

While Brown is quick to say that Giuliani’s “zero tolerance” philosophy should apply to police misconduct as well as to crime, he has little interest in wading into a philosophical discussion about the underlying causes of social unrest. “During the campaign, one of my opponents said, ‘We don’t have a crime problem, we have a poverty problem,'” Brown recalled recently. “That’s not true. We have a poverty problem, and we have a crime problem, and we have to deal with both. While you wait for great social change, you have to make sure our streets are safe.”

Having discussed the topic on the airwaves with people like Jonathan Kozol and Sister Helen Prejean, Brown understands the link between crime and poverty quite well. But he also knows that political success is measured in four-year increments. If Brown still has his eye on the national stage–and, reports the San Francisco Chronicle, he recently hinted that he might make one more run for president–he doesn’t have time to dabble in utopian visions, or to invest in long-term solutions to the intractable problems of urban poverty. His experiment in municipal governance will be judged according to the criteria used by the compilers of the “Most Livable City” rankings promulgated by street-map publishers and lifestyle magazines: safe streets, clean parks, attractive schools, high property values, and a decent selection of boutiques and restaurants.

The canvas on which Brown’s vision of a new Oakland will be drawn is the city’s sprawling downtown, a medley of skyscrapers, residential hotels, Victorian and beaux arts office buildings, and boarded-up storefronts. Once a thriving commercial and business district, the downtown lost both customers and businesses to the suburban migration of the 1950s and ’60s. Since then it has been further depleted by wrecking-ball redevelopment strategies, expensive construction scandals, and the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake, all of which have conspired to give it the haggard, has-been appearance of a former beauty queen fallen on hard times.

Brown believes the downtown can be reanimated by attracting 10,000 new residents to the central city, and city planners have been working long hours mapping out the parcels where new market-rate apartment complexes could be built. In Brown’s vision, most of the people who move into these units will be suburban commuters ready to return to Oakland, or San Francisco-based professionals attracted by the lower price of real estate on the eastern side of the bay. Either way, the new residents will be relatively well-to-do: The city planning agency, after commissioning an independent market study, estimated they will need a minimum annual household income of $75,000 to afford the new housing without some kind of additional financial aid.

Brown sees the future influx of these middle- to upper-income residents as a way of returning wealth to the urban core–“a repatriation of dollars,” as one of his supporters in the business community puts it. Others see it as good old-fashioned gentrification. “It’s kind of a trickle-down economic development model,” says skeptical Oakland housing advocate Sean Heron. “His take seems to be: ÔIf we get a lot of rich people here, that’ll make this a healthy city.’ That’s a little simple.”

Will those rich people share a common skin tone too? Oakland now ranks as one of the most integrated cities in the country, with a population that’s 43 percent black, 14 percent Asian, and 14 percent Latino. But as housing prices swell, buoyed by the booming economy in nearby Silicon Valley and the inflated real estate market in San Francisco, many wonder how long that diversity will last. Brown is the city’s first white mayor in two decades, and as a relatively recent emigrant to Oakland from San Francisco, he has become a potent symbol of demographic change. “Oakland is losing 1¸ to 2 percent of its African American population annually,” Glover says. “Some feel that the direction of Oakland’s planning is going to be [toward] Cappuccino Row.”

Brown sees such concerns as premature. “Is it 10,000 white people, 10,000 Latinos, 10,000 African Americans?” he asks. “No, it’s people. And yes, we want people with some capital.”

That some are already worried that Jerry Brown’s Oakland will be too white, too rich, or too sterile indicates just how profoundly they believe that Brown has the power to overcome the multitude of forces that have conspired against American cities. Despite the current cavils of disappointed progressives, the man has an uncanny ability to be all things to most people, and whether his Oakland is destined to be a solar-powered Ecopolis, a prosperous suburb, or a revitalized urban center depends largely on whom you ask. All that Oakland’s mayor wants people to keep in mind is that he’s committed to the task of transformation: “I’m not satisfied with the crime reduction that’s going on, I’m not satisfied with what’s being produced in the schools, I’m not satisfied with the way downtown is developed, I’m not satisfied with the way neighborhoods look,” he told the Oakland Tribune in March. “I’m going to change that if it’s the last thing I do.”