Image: AP/Wide World Photos

During its late 1990s heyday, the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum was a boisterous celebration of a global boom that was thought to have no downside. Glitzy CEOs like Steve Case and Bill Gates were accorded rock-star treatment as they expounded on a broadband future while think-tankers forecast spectacular opportunities for the world’s impoverished. The sleepy resort town of Davos, Switzerland, the longtime site of the WEF summit, burst at the seams with a polyglot crew of cell phone-toting executives — a unique species of Digital Era chieftains that The New York Times wryly terms “Davos Man”.

But as the latest WEF confab opened in New York City Thursday morning, the mood was notably gloomier, tempered by two years of stagnant economic growth and the tragedies of Sept. 11. Anti-globalization protests overshadowed last year’s Davos meeting, and the 2002 participants are fretting over a deepening, worldwide recession that cannot be quickly patched over with technological innovations or handshake deals. The latest issue of Worldlink, the WEF’s official magazine, acknowledges that adversity on its cover in big, bold letters: “CHANGED”.

Which is not to say that Davos Man is nearing extinction. Far from it.

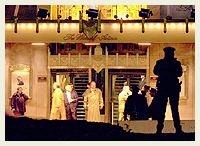

By 9 a.m. this morning, the perfume-scented lobby of Manhattan’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel was teeming with men in crisp wool suits, chattering away on cell phones in a dozen different languages. They weaved around display cases featuring H. Stern diamonds and sullen maids outfitted in traditional black-and-white French ensembles. Observing the bustle were scores of burly undercover cops, who stood solemnly at every available doorway, eyeing the badges of any visitor who seemed slightly out-of-place.

To the WEF’s great relief, the area surrounding the hotel was surprisingly calm. Two years ago, on the first day of the A-16 protests in Washington D.C., the streets around the World Bank meeting were already full of guerrilla theater groups, crudely constructed floats, and plenty of placard wavers. Yet on my walk up Madison Avenue this morning, the only placard waver I saw was hawking cheap electronics for a nearby store. The only protest within a stone’s throw of the hotel consisted of Falun Gong supporters, who cheerfully handed out graphic leaflets and exercised in unison. I espied one ski-cap clad youth trying to educate a bored-looking cop about the horrors of tear gas, but no other teach-ins were to be found. (Rumor has it that the first action will come on Saturday, when several anti-globalization groups are said to be planning a blockade to stop WEF revelers from attending a gala soiree on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.)

Despite the relative quiet in New York, the WEF’s rhetoric and approach have clearly been affected by last year’s confrontations in Davos. Several times during his introductory remarks, WEF president Klaus Schwab used the word “stakeholders” to describe the entire world’s population, a clear attempt to emphasize that the organization believes everyone — from high-tech CEO to subsistence farmer — has something to gain from international cooperation.

“We need to do infinitely better to protect all the stakeholders,” he urged the audience. “Our meeting here is, in a real sense, a vast construction project — [for] the construction of a better world for all.”

That the WEF has learned a lesson from the anti-globalization ferment was most evident in the participation of U2 lead singer Bono in an otherwise sappy panel discussion entitled “For Hope”. Between the gentle platitudes offered by South Africa’s Archbishop Desmond Tutu (“In the end, goodness prevails over evil, right prevails over wrong”) and Elie Wiesel (“Give a minute, just a minute a day, to the children”), Bono pushed the Forum to prove that they’re listening to their critics.

“It’s great to be in the Waldorf, and I’m a spoiled rotten rock star, and I drink champagne and I eat the cake,” he said. “There is a sense that we are just chatting. The protestors who are outside, the vast majority of them are passionate. They may not have a sharpened agenda, and there are a few troublemakers, but they have passion.”

Bono’s two pet causes are debt forgiveness and the AIDS crisis in sub-Saharan Africa, and he pulled few punches in discussing both, going so far as to accuse his listeners of thinly veiled racism when it comes to the latter problem.

“Now we’ve kind of accepted, yes, women and blacks are equal. But if we’re honest [about Africans], we really don’t think that they are, we really don’t think that they care about their children as much as we do.” And when he railed against the West’s habit of keeping Third World nations in virtual “debtors’ prisons,” he drew perhaps the warmest applause of the entire session.

Of course, that does not mean that the WEF is any less committed to the concept of globalization — a point driven home in a sermon by Kaspar Villiger, president of the Swiss Confederation.

“Two-thirds of the worlds’ people are excluded from the opportunities provided by globalization, and terrorists and criminals operate globally,” he said. “This brings up the question, should we reverse globalization, or should we add measures that might mitigate its harms?” A history buff, he noted that the tendency of early 20th century nations toward isolationism was a root cause of World War I, and suggested that a similar retreat from international bonds now could lead to a similar catastrophe. Striking a more ominous note, he suggested that freedom “has its price — it must be used responsibly … or freedom will endanger itself.”

The rest of the day was neither so stirring nor so cryptic. Though protestors may envision the WEF summit as a series of sinister cabals, during which cigar-chomping leaders divvy up the planet’s spoils, the session’s public face is far more boring. Straitlaced corporate vice-presidents, wired on coffee and sated on rubber chicken lunches, are shoehorned into hotel conference rooms, where they listen to professors, consultants and other big-brained types speculate on wonkish dilemmas; it’s akin to a power-mongering version of an anthropologists’ convention.

There is the inescapable sense that the truly important developments are taking place behind closed doors, far from public scrutiny — a suspicion supported by a WEF staffer who said “the real power meetings are ones that you and I will never know about, taking place in suites on the 23rd floor.”

Whatever may be happening in the Waldorf’s posh suites, the public sessions offer few insights of earth-shaping significance. At one early session, for example, provocatively titled “A Safer World: How Do We Get There?”, an array of Western security experts meditated on the future of the War Against Terrorism. The panel’s moderator, Newsweek International editor Fareed Zakaria, caused a few to sweat when he guessed that upwards of 70,000 Al Qaeda members may still be at large; another panelist, Stratfor’s George Friedman, caused only a few guffaws when he matter-of-factly stated: “There is a solution to [weapons] proliferation, and this is bombing them.”

Most of the audience members for these chats are typical corporate high-rollers; during the drabber moments of the day, I played a little game by flipping through the participants guide and marveling at the sheer number of people whose job titles included the words “chief” and “officer”. But a few social-justice advocates tried to make their presence felt, too.

One of the sharpest voices belonged to Sara Horowitz, founder of Working Today, a Brooklyn-based group which defends the rights of temporary workers. An ex-public defender and union organizer, she loudly questioned whether WEF members were masking job cuts by hiring contract labor in lieu of full-time employees — the better to avoid paying for benefits, or dealing with unions.

“I think that question is potentially explosive,” agrees James O’Toole, a business professor at the University of Southern California. “Not only have we put investments off the books, we’ve put workers off the books. We don’t know the long-term implications of that; it could have a larger impact than the accounting practices we have now.”

Dissenters also weighed in on the debate surrounding the West’s duty to ensure that perpetrators of genocide and other crimes against humanity are brought to justice. Ken Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, was critical of what he perceives to be an American hypocrisy when it comes to international due process. Though the US rarely hesitates to use its military might to strike against security threats, he argued, “the US is also the number one opponent of international courts, because they could apply to US citizens. That’s a double standard that’s harming our legitimacy.”

Sadly, echoes of lingering hatreds drowned out these voices of reasonable, intelligent dissent. The WEF may be committed to encouraging dialogue between nations, but a few days spent in a posh hotel is not enough to paper over decades of contempt and suspicion. Yes, there are rumors that Shimon Peres will meet with Palestinian leaders at the Waldorf, which could be a welcome first step towards a rapprochement. But as the events at a panel entitled “The Roots of Conflict” demonstrated, other animosities still simmer. Omar Abdullah, an Indian cabinet minister, went out of his way to mention that, for most of its history, “Kashmir has been one of the most peaceful places on Earth. It’s only when Pakistan has chosen to bring violence across our border that there has been violence.” As one might guess, a Pakistani in the audience was not amused, and a war of words ensued.

The unease of that debate stayed with me through the evening, as I stood in the Waldorf’s grand ballroom and watched a music video entitled “The Darkest Hour is Just Before Dawn.” Produced specially for the meeting, it featured actor Matthew Modine reading stirring quotes from Chief Seattle, Buddha, and Martin Luther King Jr., as the camera swooped over images of peace rallies and smiling orphans. The last shot depicted the last moments of a solar eclipse, as the light started to flood back into the sky as the moon moved onwards. Only the densest of viewers could miss the optimistic, if rather self-congratulatory, point of it all.