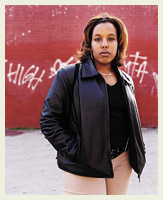

Image: Ashton Worthington

When Selemawit Tewelde helped organize a sit-in at the Philadelphia Board of Education last December, all she could do was give a speech while 11 of her fellow students risked arrest for occupying the building. “I wanted to do it so bad,” she recalls, “but my mother, she wouldn’t let me get arrested.” It’s not easy being an activist when you’re only 16.

Tewelde got involved in the sit-in to protest plans to turn over 45 of the city’s lowest-performing schools to Edison Schools Inc. or another for-profit company. The state took over Philadelphia’s debt-ridden school system last winter, and officials want to see if a private firm can do a better job of repairing buildings, easing violence, and boosting test scores. The plan would be the nation’s largest experiment in school privatization, and Tewelde’s school, John Bartram High, is considered a likely candidate.

But the high school junior is not about to see her school privatized without a fight. Each Saturday morning, Tewelde takes the trolley downtown to the offices of the Philadelphia Student Union, a citywide organization of high schoolers. There she plans a weekly meeting that brings together student organizers from across the city. With Tewelde serving as “facilitator,” the group discusses ways to fight privatization, planning teach-ins, protest marches, and acts of civil disobedience. On December 18, thousands of students walked out of classes to demonstrate their opposition to Edison and marched on City Hall wearing stickers that read, “I am not for sale. Say no to privatization.”

With her confident demeanor, Tewelde shows up frequently on the evening news addressing crowds of protesters. “I’m always the type to speak up when I feel like something’s going wrong,” she says — a quality she believes she inherited from her mother, Ahdega Tezre, an immigrant from Eritrea.

Tewelde cites a host of problems with privatization, especially given the questionable track record of Edison Schools nationwide (see “Reading, Writing and Revenue,” May/June 2001). Her primary concern, however, involves accountability: If schools are privatized, administrators will answer to corporate shareholders instead of to students and parents. “It’s hard to get the mayor to listen to me,” she says. “How would this company listen to me?”

Tewelde says that increased funding, not privatization, is the best way to fix problems at troubled schools. Bartram has the honor of being on the National Register of Historic Places, but it’s also crumbling. “The ceiling shouldn’t be falling apart,” says Tewelde. “We shouldn’t have messed-up floors.” She believes more funding is also needed to provide counseling and other services to address the causes of student violence, rather than relying on the metal detectors and surveillance cameras installed at Bartram.

Tewelde knows that she and other student activists are making a difference. As a consultant to the state during the Philadelphia takeover, Edison Schools was considered the most likely candidate to privatize the city’s schools. But organized opposition has already caused officials to solicit interest from 32 other bidders, and Tewelde is confident that students can force the state to scrap its plans to privatize.

“A lot of students probably think, ‘I don’t care, since nobody’s asking me how I feel about what’s going on with this,'” she says. “That’s how everything gets messed up. Young people start to feel powerless, but they’re not. They’re very powerful — and they need to understand that.”