Image: AP/WideWorld

When Catholic leaders gather in Dallas this June, their deliberations will undoubtedly be followed by millions. The Rev. John R. Hanlon, however, might be expected to watch the events with particular interest.

Convicted in 1994 on two counts of rape and two counts of assault with intent to rape, Hanlon is currently serving three life-sentences at Norfolk Bay State Correction Facility in Massachusetts. But a 1997 Mother Jones investigation found that Hanlon was still recognized by the Catholic Church as a priest in good standing and was still receiving church retirement benefits.

If history is any guide, Hanlon will likely remain on the Church payroll regardless of what Catholic leaders agree to in Dallas.

Following last month’s historic summit at the Vatican, US Catholic leaders struggled to assure their skeptical flock that priests whose actions have made them “notorious” or those shown to have repeatedly abused children would be dismissed.

“We’re also looking … to facilitate the way to dismiss someone who does not qualify as a notorious offender. So they want to be able to dismiss anybody who puts children at risk,” says Sister Mary Ann Walsh, spokesperson for the United State Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Still, any new policies which emerge from the Dallas meeting will probably only apply to new or recent allegations of abuse. Experts on church law say a retroactive approach — which might result in the dismissal of priests who are known to have molested children in the past — would be unlikely. So Hanlon, whose very public conviction would seem to have made him “notorious,” will probably escape any Church proceeding.

In 1997, writing from prison, Hanlon insisted he had never been dismissed from the priesthood.

“I am not suspended; I have not left; I am officially recognized as retired,” Hanlon stated in the 1997 letter. “On the advice of my counsel and the archdiocesan authorities, I am not free to discuss financial matters. But I can honestly say that I have never been forgotten or neglected.”

Five years later, Church officials still refuse to say whether Hanlon remains in order or is receiving financial support. Repeated requests from information from the Archdiocese of Boston went unreturned or were met with a “no comment.” Attempts to contact Hanlon again as well as his lawyer, Marshall E. Johnson, were also unsuccessful.

The gathering of church leaders in Dallas will likely result in changes to or clarifications of Church policy. Advocates for abuse victims, however, say they are more interested in seeing the church better support criminal or civil proceedings against priests accused of abuse.

“First thing’s first; let’s protect kids, lets get these guys locked up and then worry about whether they get to wear a roman collar ever again,” says David Clohessy, the national director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, a Chicago based national support group. “It’s a whole question of priorities. We are focused on prevention. The bishops are focused on after-the-fact questions.”

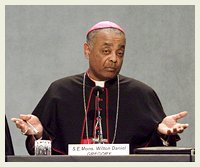

Despite repeated requests, US Conference of Catholic Bishop president Wilton Gregory declined to comment on what might be considered at the June meeting. Bishop William Skylstad, the vice president of the Conference of Catholic Bishops, also declined to comment, as did Bishop Theodore McCarrick, of Washington, D.C.

According to experts in Canon law, the rules created by Catholic authorities to govern the Church, Christian organizations, and its members, there is little question that priests with records like Hanlon’s should be considered “notorious” in the eyes of the Church. But those same experts say it is unlikely that Hanlon would be expelled from the priesthood now, eight years after his conviction.

“My understanding is that ‘notorious’ in canon law means much the same as in any ordinary context: ‘publicly known,” says the Rev. John Renken, a Canon lawyer and Co-Pastor of St. James Parish in Riverton, Illinois. “Something can be notorious even if it is not proven in a civil or canonical court, obviously.”

Father Arthur J. Espelage, Executive Coordinator of the Washington, D.C.-based Canon Law Society of America, says, “the legal tradition in the Catholic Church has not been for the retroactivity of penalties.” Still, Espelage says he understands why such a step might seem appropriate in the case of a priest found guilty of rape.

“I know that people are saying in the public press that if a priest has been guilty of hurting a child in the past, that he should be out from this day on,” Espelage says. “I hear that loud and clear and I have nephews and nieces and I can’t disagree with that.”