On September 20, the Bush administration published a national security manifesto overturning the established order. Not because it commits the United States to global intervention: We’ve been there before. Not because it targets terrorism and rogue states: Nothing new there either. No, what’s new in this document is that it makes a long-building imperial tendency explicit and permanent. The policy paper, titled “The National Security Strategy of the United States of America” — call it the Bush doctrine — is a romantic justification for easy recourse to war whenever and wherever an American president chooses.

This document truly deserves the overused term “revolutionary,” but its release was eclipsed by the Iraq debate. Recall the moment. Bush, having just backed away from unilateralism long enough to deliver a speech to the United Nations, was now telling Congress to give him the power to go to war with Iraq whenever and however he liked. Congress, with selective reluctance, was skating sideways toward a qualified endorsement. The administration had fended off doubts from the likes of George Bush Sr.’s national security adviser Brent Scowcroft, and retreated from its maximal designs (at least on Tuesdays and Thursdays), giving doubters, and politicians preoccupied with their reelection, reasons to overcome their doubts and sign on.

The Bush White House chose this moment to put down in black and white its grand strategy — to doctrinize, as it were, its impulse to act alone with the instruments of war. Hitching a ride on Al Qaeda’s indisputable threat, the doctrine generalizes.

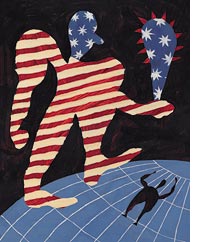

It is limitless in time and space. It not only commits the United States to dominating the world from now into the distant future, but also advocates what it calls the preemptive use of force: “America will act against emerging threats before they are fully formed.”

The United States has many times sent armed forces to take over foreign countries for weeks, years, even decades. But the Bush doctrine is the first to elevate such wars of offense to the status of official policy, and to call “preemptive” (referring to imminent peril) what is actually preventive (referring to longer-term, hypothetical, avoidable peril). This semantic shift is crucial. When prevention of a remote possibility is called preemption, anything goes. CIA caution can be overridden, Al Qaeda connections fabricated, dangers exaggerated — and the United States will have a doctrine to substitute for international law.

The Bush manifesto displays bluster, romance, and illogic in equal measure. Premise: America is fundamentally righteous. “In keeping with our heritage and principles, we do not use our strength to press for unilateral advantage.” This will be news to much of the world, but never mind. An imperial strategy is justified because there is in the world but “a single sustainable model for national success: freedom, democracy, and free enterprise” — a model that, surprise, the United States embodies. (As for success without freedom or democracy or free enterprise, what about China? As for free enterprise and democracy of a sort without success, what about Argentina?) Conclusion: Whatever America does will be right — pursuing terrorists, preemptive war, free trade, whatever. Nuance be damned. For all the boilerplate about national differences, the doctrine’s key concern is clear: If all the world speaks American values (though sometimes in funny local accents), why shouldn’t everyone dance to our tune?

Look closer, and even the document’s core phrases lose their meaning. Just what is “a balance of power that favors freedom” — a term the authors use no fewer than four times? Perhaps the answer is implicit in the doctrine’s insistence that no rivals shall be permitted to exercise power the likes of America’s: “Our forces will be strong enough to dissuade potential adversaries from pursuing a military buildup in hopes of surpassing, or equaling, the power of the United States.” Balance, indeed.

The doctrine goes beyond the preemption theme sounded by President Bush in a West Point speech last June. Read beneath its kitchen-sink rhetoric and you see, in black and white, Bush codifying the unilateral treaty-busting moves of his first months in office — his rejection of the Kyoto climate-change protocol, his cancellation of the ABM accord, his obstruction of the bioweapons treaty, and his flat withdrawal from participation in the International Criminal Court, to name only the most dramatic. Those go-it-alone exercises were not casual or tactical retreats from global cooperation. They were applications of a new policy that had not yet been spelled out. The September manifesto does spell it out: The United States rules.

The core of the National Security Strategy is unilateralist, but it pays tribute to consultations with allies and “good relations among the great powers.” It is militarist, though it nods in the direction of democracy and development. Make no mistake: There’s no big surge in development aid forthcoming. Nor, from an oil administration, any recognition that global warming inflicts irrevocable damage and that sustainable energy is a security issue — for us as well as the impoverished nations whose well-being the doctrine purports to care about. In Bush Country, there’s no downside to free trade, which it calls “a moral principle,” no corporations ravaging forests or pushing peasants off their land. The document does, however, pause to put in a good word for lower tax rates.

It would be easy to dismiss Bush’s manifesto on the grounds that it is a thumpingly cliché-ridden monstrosity, a heap of Washington pixels expended because Congress in 1986 mandated periodic reports on national security strategy. The document is meant not so much to be read as to be brandished. This is internationalism imperial-style — as in Rome, when Rome ruled. Its scope is breathtaking. There were large parts of the world that Rome couldn’t reach, but the Bush doctrine recognizes no limits.

The government of the United States will ask not so much as a by-your-leave. It will know when threats are emerging, partly formed, and it will not have to say how it knows, or be convincing about what it knows. The doctrine affirms all of the comforts and recognizes none of the dangers of empire. It ignores the costs of unbounded deployment and war. It acknowledges no danger that reckless swashbuckling helps recruit terrorists. It forgets that all empires fall — they cost too much, they incite too many enemies, they inspire contrary empires. The new imperialists think they are different. All empires do.

Robert Jervis, a professor of international politics at Columbia University and a leading foreign-affairs realist in the academy, calls the document’s rhetoric “incredibly ambitious and incredibly activist.” As a declaration of American strategy vis-à-vis the world, it is, Jervis believes, “the boldest public statement since 1947,” when containment became policy and the Truman Doctrine committed the United States to intervene against communist insurgencies around the world. Like the Bush doctrine, containment was open-ended; unlike the new doctrine, it was predicated on a network of alliances and multinational organizations, of which nato was the most formidable.

Bush now trades in alliances for ad hoc “coalitions.” He makes a pass at disguising unilateralism as “a distinctly American internationalism that reflects the union of our values and our national interests.” Interestingly, the doctrine retroactively downgrades the old threat, characterizing Soviet communism as “a generally status quo, risk-averse adversary.” (If only Ronald Reagan had grasped that before he committed the country to the massive deficits of the 1980s.) Bush and his allies want their challenge to surpass all previous challenges, their terrain to extend beyond all previous terrains. The whole world is their turf.

Now, some things are true even if George W. Bush says them. It is true and important that Al Qaeda and its brethren are uncontainable and undeterrable. American power does sometimes serve a larger good — as it would in the Middle East, were Bush wise enough to exert it on behalf of a two-state Israel/Palestine solution. But Al Qaeda is not the Bush doctrine’s principal target, nor does it have more than a few words to spare about the Middle East. Terrorism is the occasion for what is really a doctrinal update. The National Security Strategy proclaims the virtue of a power extension — call it regime extension — that its authors have sought for years.

During his campaign for the presidency, George W. Bush never so much as hinted at the grandiosity of the vision he has now loosed upon the world. But don’t think that it erupted out of the blue after the massacres of September 11. The emphasis on preemption is new, but on the whole, the National Security Strategy is the most recent version of a go-for-broke imperial outlook that has emerged over the last decade. The first version was drafted in 1992 by then-Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney’s then-subordinate Paul Wolfowitz; the leaked document was repudiated by then-President Bush. A successor manifesto was drawn up in 2000 over the names of Wolfowitz and others who soon thereafter landed high positions in the administration of George Bush II. Both documents emphasized pumping up American military power to such a high pitch that rivals would opt not to compete. Both emphasized far-flung bases and unilateralism. The new doctrine thus represents the triumph of the Cheney-Rumsfeld-Wolfowitz group, who have sought to establish an American Millennium ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

If Bush had doubts about regime extension before September 11, he surely does no longer. The moralism of a president with a mission has now fused with the parochialism of a man whose well of world knowledge is filled with oil. He will take the battle to the enemy, even if the enemy is far-flung, even if allies are frightened and skeptical, even if the political and economic costs of war are immense. (Since the economic costs will fall mainly on America’s poor and middle class and will have the effect of forestalling any progressive spending initiatives at home, they do not concern him unduly.) Americans know fear now, so fear is what he will mobilize. Americans want multilateralism, so he patches together ad hoc coalitions, even goes to the United Nations — once he has already decided on war.

The doctrine is so sweeping that it discredits what might have been, from another hand, more modest imperatives. There is surely (as the U.N. Charter insists) a case to be made for national self-defense as a last resort. There are organizations like Al Qaeda whose purposes can properly be called genocidal, and it is not clear how, in the years to come, they and their purposes are to be coped with. Critics of American bravado are obliged to address the question in earnest. It is mightily worth underscoring that, as the document says, “international obligations are to be taken seriously. They are not to be undertaken symbolically to rally support for an ideal without furthering its attainment.”

But the document undermines its own most defensible points because it exudes the spirit of take-it-or-leave-it. It carries out Bush’s impulse to rip-roar through obstacles after a bit of small-group communion. It has all the logic of the Republican Supreme Court majority in Bush v. Gore, the logic that put W in the White House, the logic that now leads the charmed circle of Bush, Cheney, Rumsfeld, Wolfowitz, and Rice to make enormous decisions behind closed doors without much consultation (except an occasional nod to Colin Powell). It has the bluster of an administration that presses the intelligence agencies to sign onto its view of how things must be, against their better judgment. This is the manifesto of a bully with a ferocious will who fumbles in search of reasons to explain why he does what he feels like doing.

If you thought the promulgation of such a manifesto would be big news, you would be mistaken. On release, the National Security Strategy was jabbed at by a few opposition politicians, picked apart in a handful of newspaper columns, and promptly sank from sight. On television, it hardly even happened. That Democrats paid attention to the Bush doctrine at all is to the credit of Al Gore, who in a September 23 speech in San Francisco said that it conveys “one of the most fateful decisions in our history: a decision to abandon what we have thought was America’s mission in the world.” He concluded that the new doctrine destroys “the goal of a world in which states consider themselves subject to law” in favor of “the notion that there is no law but the discretion of the president of the United States.” No major network deigned to take more than passing note of his speech.

As a nation, we’re still in a trance. The leadership of the most powerful nation-state on earth proceeds to set out its grand strategy, its unified theory of everything, and its prime channels of information don’t see fit to let the populace in on the news that their government is hell-bent on empire and has said so in black and white.

Nonetheless, Bush’s strategy is now in force. It confirms suspicions and stokes paranoia. In propounding that there are no more than two models for how a society lives in the world, and that those who despise the one must enlist behind the other, it indulges in the same drastic oversimplification that motivates the terrorists. Americans will have to contend with the consequences for generations. This is why the Bush doctrine is dangerous: It’s a gift to anti-Americans everywhere.