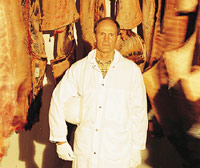

Photo: <a href="http://www.andrewgeiger.com/" target="new">Andrew Geiger</a>

Bad Meat made an activist out of John Munsell. Before the tainted beef arrived—USDA-approved and vacuum-sealed—at Montana Quality Foods, Munsell’s family-run packing plant, this die-hard Republican had no reason to doubt the integrity of the food-safety system. But that changed after the meat he ground for hamburger tested positive for E. coli 0157:H7, a potentially deadly pathogen found in cattle feces that sickens thousands every year.

Instead of tracking the contaminated meat back to its source, the USDA launched an investigation of Munsell’s own operation in Miles City, Montana. Never mind that the local federal inspector had seen the beef go straight from the package into a clean grinder—a USDA spokesman called that testimony “hearsay.” By February 2002, three more tests of meat Munsell was grinding straight from the package came back positive in USDA tests for E. coli. This time, as he would later testify in a government hearing, he had paperwork documenting that the beef came from a single source: ConAgra’s massive Greeley, Colorado, facility, which kills as many cows in three hours as Montana Quality Foods handles in a year.

Munsell fired off an angry email to the district USDA manager, warning of a potential public-health emergency, and adding that if no one tracked down the rest of the bad meat, “both of us should share a cell in Alcatraz.” The agency moved immediately and aggressively—not to recall meat from Greeley, but to shut down Munsell’s grinding operation, a punishment that lasted four months.

Despite Munsell’s continued whistleblowing—to Senator Conrad Burns (R-Mont.), national cattle associations, and his fellow meat processors—the USDA failed to address the alleged contamination at ConAgra’s Greeley plant. Then, in July 2002, Munsell’s worst fears came true. E. coli-tainted burger from Greeley killed an Ohio woman and sickened at least 35 others. ConAgra then recalled 19 million pounds of beef, one of the largest recalls in history. (As much as 80 percent of the meat had already been consumed.)

“I want the world to know what the real policies are,” says Munsell, driving through Miles City, a ranching town on Montana’s eastern plain where the casinos compete with saddle shops on Main Street and the men don’t take their hats off for much. “The real policies imperil the consumer,” he says. “The USDA doesn’t want that out.”

Lanky, with thinning sandy hair, the 57-year-old Munsell speaks in a measured voice that barely hints at the fury he feels. Though his battle with the USDA has crippled his business, Munsell is now on the offensive. After months of lobbying, he persuaded Senator Burns to convene a congressional hearing in Billings last December, where Munsell testified on the failings of USDA inspections. Munsell also convinced the Government Accountability Project (GAP)—the nation’s leading whistleblower organization—to investigate the USDA’s handling of his case. In July 2003, GAP released a major report titled “Shielding the Giant: USDA’s ‘Don’t Look, Don’t Know’ Policy for Beef Inspection.” “The ConAgra-Munsell scandal,” it concluded, “perpetuates a long-standing USDA pattern to blame the messenger and scapegoat the victims, rather than stand behind its seal of wholesomeness.”

Why would the USDA willfully ignore a whistleblower and stand by as feces-tainted meat entered grocery stores? Two decades of federal reforms have left more and more regulation in the hands of the meat industry itself. “Agribusiness runs the show” at the USDA, says Tony Corbo, a food-safety lobbyist with the watchdog group Public Citizen.

In 1998 the USDA stopped testing for E. coli at the company’s Greeley facility, saying internal safeguards were sufficient. While tests continued at small plants like Munsell’s, the USDA allowed big packers to conduct their own in-house tests. Indeed, according to the congressional investigation of the ConAgra recall initiated by Rep. Henry Waxman (D-Calif.), 33 in-house tests conducted at ConAgra’s Greeley facility in the month before the recall came back positive for E. coli contamination. ConAgra failed to alert the USDA. In a scathing letter to Agriculture Secretary Ann Veneman this spring, Waxman wrote that the USDA’s policy of industry self-regulation “appears grossly inadequate to protect the public health.”

Munsell has steadily been winning allies in his fight for reform. “This guy is the small businessman. He’s done everything right,” says Brad Keena, a spokesman for Rep. Denny Rehberg (R-Mont.), who has followed Munsell’s case closely. “But because he’s the middleman, his reputation gets ground into the problem of the larger company.” (Swift & Co., which boughtConAgra’s meatpacking operations last year, insists there is no conclusive evidence that the Greeley plant was responsible for Munsell’s bad meat.)

To this day, the USDA maintains that it followed all of its own policies in regard to ConAgra and boasts of new safeguards that were put into place after the recall. USDA spokesman Steve Cohen also argues that Munsell never proved the source of the initial E. coli contamination and suggests that he “got a good deal” on the ConAgra meat. Munsell isn’t rattled by such accusations. “He is simply grasping at straws,” he says.

The negative publicity from the USDA’s shutdown of his plant has proved fatal to business. This summer, Munsell put his operation up for sale, foretelling the end of a business that his father—who, at the age of 84, still serves breakfast to the crew—founded in 1946. But Munsell has no regrets. What haunts him is not his decision to go public, he says, but the fact that he almost decided to stay quiet, just to protect his own livelihood. “You know what it comes down to?” says the third-generation meatpacker, his steady composure beginning to crack. “My grandkids. The USDA could care less about the health of my grandkids.”