Illustration Courtesy of: Anti-Slavery International

Strangely, in a city where it seems that on every block a blue-and-white glazed plaque commemorates a famous event or resident, none marks this spot. All you can see today, after you leave the Bank station of the London underground, walk a block or two east, and then take a few steps into a courtyard, is a couple of low, nondescript office buildings, an ancient pub, and, on the site itself, 2 George Yard, a glass-and-steel high-rise. Nothing remains of the bookstore and printing shop that once stood here, or recalls the late afternoon in 1787 when a dozen people-a somber-looking crew, one man in clerical black and most of the others not removing their high-crowned blade hats-filed through its doors and sat down to launch one of the most far-reaching citizens’ movements of all time. Cities build monuments to kings and generals, not to people who once gathered in a bookstore. And yet what these particular citizens did was felt across the world-winning the admiration of the first and greatest student of what today we call civil society. What they accomplished, Alexis de Tocqueville wrote, was “something absolutely without precedent in history…. If you pore over the histories of all peoples, I doubt that you will find anything more extraordinary.”

To fully grasp how momentous was what began at 2 George Yard, picture the world as it existed in 1787. Well over three-quarters of the people on earth are in bondage of one land or another. In parts of the Americas, slaves far outnumber free people. African slaves are also scattered widely through much of the Islamic world. Slavery is routine in most of Africa itself. In India and other parts of Asia, some people are outright slaves, others in debt bondage that ties them to a particular landlord as harshly as any slave to a Southern plantation owner. In Russia the majority of the population are serfs. Nowhere is slavery more firmly rooted than in Britain’s overseas empire, where some half-million slaves are being systematically worked to an early death growing West Indian sugar. Caribbean slave-plantation fortunes underlie many a powerful dynasty, from the ancestors of Elizabeth Barrett Browning to the family of the fabulously wealthy William Beckford, lord mayor of London, who hired Mozart to give his son piano lessons. One of the most prosperous sugar plantations on Barbados is owned by the Church of England. Furthermore, Britain’s ships dominate the slave trade, delivering tens of thousands of chained captives each year to French, Dutch, Spanish, and Portuguese colonies as well as to its own.

If you had proposed, in the London of early 1787, to change all of this, nine out of ten people would have laughed you off as a crackpot. The 10th might have admitted that slavery was unpleasant but said that to end it would wreck the British Empire’s economy. It would be as if, today, you maintained that the automobile must go. One in ten listeners might agree that the world would be better off if we traveled instead by foot, bicycle, electric train, or trolley, but are you suggesting a political movement to ban cars? Come on, be serious! Looking back, however, what is even more surprising than slavery’s scope is how swiftly it died. By the end of the 19th century, slavery was, at least on paper, outlawed almost everywhere. Every American schoolchild learns about the Underground Railroad and the Emancipation Proclamation. But our self-centered textbooks often skip over the fact that in the superpower of the time slavery ended a full quarter-century earlier. For more than two decades before the Civil War, the holiday celebrated most fervently by free blacks in the American North was not July 4 (when they were at risk of attack from drunken white mobs) but August 1, Emancipation Day in the British Empire.

Jettisoning “Cargo”

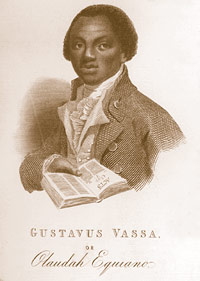

On March 18, 1783, the Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser carried a short letter to the editor about a case being heard in a London courtroom. The item caught the eye of a former slave living in England, Olaudah Equiano. Horrified, he ran immediately to see an Englishman he knew, Granville Sharp, an eccentric pamphleteer and known opponent of slavery. Sharp recorded in his diary that Equiano “called on me, with an account of one hundred and thirty Negroes being thrown alive into the sea.”

Months earlier, under Captain Luke Collingwood, the ship Zong had sailed from Africa for Jamaica with some 440 slaves, many of whom had already been on board for weeks. Head winds, spells of calm, and bad navigation (Collingwood mistook Jamaica for another island and sailed right past it) stretched the transatlantic voyage to twice the usual length. Packed tightly into a vessel of only 107 tons, slaves began to sicken. Collingwood was worried, for a competent captain was expected to deliver his cargo in reasonable health, and, of course, dead or dying slaves brought no profits. There was a way out, however. If Collingwood could claim that slaves had died for reasons totally beyond his control, insurance-at £30 per slave-would cover the loss.

Collingwood ordered his officers to throw the sickest slaves into the ocean. If ever questioned, he told them, they were to say that due to the unfavorable winds, the ship’s water supply was running out. If water had been running out, these murders would be accepted under the principle of “jettison” in maritime law: A captain had a right to throw some cargo-in this case, slaves-overboard to save the remainder. In all, 133 slaves were “jettisoned” in several batches; the last group started to fight back and 26 of them were tossed over the side with their arms still shackled.

When the Zong’s owners later filed an insurance claim for the value of the dead slaves, it equaled more than half a million dollars in today’s money, and the insurance company disputed the claim. The moment Equiano showed him the newspaper article, Granville Sharp leaped into action. He hired lawyers, went to court, and personally interviewed at least one member of the ship’s crew and a passenger. But the shocking thing about the Zong case-as much to Equiano and Sharp then as to us now-is that after more than a hundred human beings had been flung to their deaths, this was not a homicide trial. It was a civil insurance dispute.

Sharp tried and failed to get the Zong’s owners prosecuted for murder. But he fired off a passionate salvo of outraged letters about the case to everyone he could think of. One letter apparently reached a prominent clergyman, who, the following year, became vice chancellor-the equivalent of an American university’s president-of Cambridge. Disturbed by what he had heard, he put to use one of the most powerful tools at his command: He made the morality of slavery the subject of the annual Cambridge Latin essay contest.

Latin and Greek competitions were a centerpiece of British university life. To win a major one was like winning a Rhodes scholarship or the Heisman trophy today; the honor would be bracketed with your name for a lifetime. One entrant in the Latin contest was a 25-year-old divinity student named Thomas Clarkson. He had no previous interest in slavery whatever, he later wrote, but only “the wish of…obtaining literary honour.” Unexpectedly, however, as he read everything he could find, studied the papers of a slave trader who had recently died, and interviewed officers who had seen slavery firsthand in the Americas, Clarkson found himself overcome: “In the day-time I was uneasy. In the night I had little rest. I sometimes never closed my eye-lids for grief…. I always slept with a candle in my room, that I might rise out of bed and put down such thoughts as might occur to me…conceiving that no arguments…should be lost in so great a cause.”

He won first prize. When it was awarded in June 1785, Clarkson read his essay aloud in Latin to an audience in Cambridge’s elegant Senate House; then, his studies finished, already wearing the black garb of a deacon, he headed off toward London and a promising church career. But he found, to his surprise, that it was slavery itself that “wholly engrossed my thoughts…. Coming in sight of Wades Mill in Hertfordshire, I sat down disconsolate on the turf by the roadside and held my horse. Here a thought came into my mind, that if the contents of the Essay were true, it was time some person should see these calamities to their end.”

“A Fire of Indignation Kindling Within Me”

It was time some person should see these calamities to their end. If there is a single point at which the anti-slavery movement in the British Empire became inevitable, it is the moment Thomas Clarkson got off his horse and sat down beside the road. When he remounted and rode onward to London, it was with the determination, first of all, to publish his essay in English. In the office of one well-known London publisher, he was dismayed that the man was interested only because the essay had won a prize. Clarkson, by contrast, “wished the Essay to find its way…among such as would think and act with me.” He had just left the publisher’s office when, on the street, he ran into a Quaker friend of his family’s. The Quakers were the only religious denomination that had come out against slavery, and the man said Clarkson was just the person he was looking for: Why hadn’t he published that essay of his?

Together, they walked a few blocks to the bookstore and printing shop of James Phillips, in George Yard, in the warren of narrow curving streets of London’s business district. Bookselling, publishing, and printing usually happened under the same roof in those days (with the printer’s family often living upstairs and perhaps a cow or pig or two in the back yard), and this was the work that Phillips did for Britain’s small Quaker community. Clarkson took an immediate liking to him, and on the spot said Phillips could publish the essay. This was the day Clarkson discovered that he was not alone.

With ferocious determination, he now dedicated himself to finding out everything he could about slavery. Many ships sailed for Africa from the docks along the Thames, and after climbing on board and exploring one, he wrote, “I found soon afterwards a fire of indignation kindling within me.” He systematically visited anyone with firsthand information: merchants, sea captains, army and navy officers. With the instincts of a good reporter, “I made it a rule to put down in writing, after every conversation, what had taken place.”

The key people he would have to work with were clearly the Quakers; they were rock-firm in their convictions, and they had a small but dedicated network around the country. To them, it was clear that Clarkson was a godsend: He was young, brimming with energy, and, above all, he was a member of the all-powerful Church of England. The major reason the Quakers’ anti-slavery efforts had so far accomplished nothing was simply because they were Quakers. People mocked them as oddballs who said “thee” and “thou,” who refused to take off their distinctive black hats except when preaching or praying, and who refused to use the names of the months or the days of the week because these derived from Roman or pagan gods instead of from the Bible. To influence public opinion, the Quakers needed a talented Anglican willing to devote all his energy to the movement, and in Clarkson, at last, they had one.

Together, Clarkson and his Quaker allies carefully planned a broad organization from both faiths. “Went to town on my mare to attend a committee of the Slave Trade now instituted,” wrote one Quaker in his diary. In the late afternoon of May 22, 1787, the group of a dozen men officially assembled for the first time, at James Phillips’ bookstore and printing shop. Probably the printers had gone home for the day, so there would have been no clanking flatbed press, but large sheets of uncut book pages would have been hanging from overhead wooden racks in the ceiling, the ink drying.

The committee targeted the slave trade, rather than slavery itself, because abolishing the first seemed within easier political reach and it also seemed likely to eventually end the second. West Indian slavery was by every measure far deadlier than slavery almost anywhere else. Cultivating sugar by hand, under a broiling sun, was-and still is-one of the hardest forms of labor on earth. Tropical diseases were rampant; the slaves’ diet was much worse than in the American South; they died younger; they had far fewer children. The death rate on the brutal Caribbean plantations was so high that the slave population would have been dropping by up to 3 percent a year if it were not for the steady shipments of new slaves from Africa. Stop the trade, abolitionists were-naively-convinced, and slavery itself would in the long run become impossible.

The committee now had to ignite its crusade in a country where the overwhelming majority of people considered slavery totally normal. Plantation profits gave a major boost to the British economy, and the livelihood of tens of thousands of seamen, merchants, and shipbuilders depended upon the slave trade. How to even begin the massive job of changing public opinion? More than nine out often Englishmen, and all Englishwomen, could not even vote. Without this most basic right, could they be roused to care about the rights of other people, of a different skin color, an ocean away?

In all of human experience, there was no precedent for such a campaign.

“Success to the Trade”

In June of 1787, Thomas Clarkson got on his horse again and set off for the big slave-ship ports of Bristol and Liverpool. He was looking for veterans of the trade who could eventually testify before parliamentary hearings. he would also distribute pamphlets and quietly set up local abolition committees. Amazingly, for many years to come, he would be the movement’s only permanent, full-time organizer.

A sense of foreboding came over Clarkson as he approached Bristol: “The bells of some of the churches were then ringing; the sound…filled me…with a melancholy…. I began now to tremble, for the first time, at the arduous task I had undertaken, of attempting to subvert one of the branches of the commerce of the great place which was then before me…. I questioned whether I should even get out of it alive.” This was not, it turned out, an unreasonable fear.

In the autobiographical history of the movement Clarkson later wrote, the very paper seems to burn with his outrage. When he tracked down information about a massacre of some 300 Africans by British slave traders on the coast of what is today Nigeria, he wrote, “It made…my blood boil…within me.”

More than 6 feet tall, Clarkson had thick red hair and large, intense blue eyes that looked whomever he spoke to directly in the face. As he stalks purposefully through the streets of Bristol, we can sense him fully finding his calling: “I began now to think that the day was not long enough for me to labour in. I regretted often the approach of night, which suspended my work.”

The brutality of the slave trade, Clarkson discovered, wasn’t confined to the mistreatment of the slaves themselves. He found a slave ship in the harbor, just returned from a voyage on which 32 seamen had died-a number larger than many a ship’s entire crew. The treatment of one sailor, a free black man named John Dean, wrote Clarkson, “exceeded all belief…. The captain had fastened him with his belly to the deck, and…poured hot pitch upon his back, and made incisions in it with hot tongs.” Dean had disappeared, but Clarkson found a witness who “had often looked at his scarred and mutilated back.”

Each discovery led to another. If slave vessels were so notoriously brutal, why did sailors continue to sign on? For several weeks, Clarkson haunted Bristol waterfront pubs to see how officers recruited their crews. “The young mariner, if a stranger to the port, and unacquainted with the nature of the Slave-trade, was sure to be picked up.” He would be told that wages were high and women plentiful. “He was plied with liquor…. Seamen also were boarded in these houses, who, when the slave-ships were going out, but at no other time, were encouraged to spend more than they had money to pay for.” The pub keeper then demanded payment, and only “one alternative was given, namely, a slave-vessel, or a gaol.”

Captains and mates refused to talk to Clarkson. But one day in the street, an overheard fragment of conversation made him follow a well-dressed man, a doctor, as it turned out, named James Arnold. He had made two slave voyages, which he described to Clarkson in gruesome detail, and was about to leave on a third. (These ships often carried doctors; healthy slaves fetched higher prices.) Arnold “had been cautioned about falling-in with me,” but spoke boldly nonetheless, explaining that he was “quite pennyless…but if he survived this voyage he would never go another.” Would Arnold be willing “to keep a journal of facts, and to give his evidence, if called upon, on his return”? The answer was yes.

Several times, Clarkson tried to get slave-ship captains prosecuted for murder. None of these attempts succeeded, but word of them got back to London, where the sober Quaker businessmen on the committee were alarmed that instead of quietly investigating, Clarkson was getting too combative. One wrote to him, “I hope the zeal and animation with which thou hast taken up the cause will be accompanied with temper and moderation.”

But Clarkson showed no moderation as he rode on to Liverpool, the world’s largest slave-trade port, which would be sending 81 ships to Africa that year. As he was walking past a ship chandler’s shop, he was shocked to see handcuffs, leg shackles, and thumbscrews in the window. He also noticed a surgical instrument with a screw device, used by doctors in cases of lockjaw. The shopkeeper explained: It was for prying open the mouths of any slaves on shipboard who tried to commit suicide by not eating. Clarkson bought one of each item; from here on, he would display them to the newspaper editor in every town he passed through. He was learning that organizing alone is not enough; you need to wage a media campaign.

At the King’s Arms tavern in Liverpool, where he stayed, men pointed him out in the dining room. “Some gave as a toast, Success to the Trade, and then laughed immoderately, and watched me when I took my glass to see if I would drink it.” Before long, he began receiving anonymous death threats. One day, looking back from the end of a pier in a heavy gale, “I noticed eight or nine persons making towards me …. They closed upon me and bore me back.” The group included one of the ship’s officers he was trying to have prosecuted for murder. At this moment, his tall, strong build saved him from harm-and possibly from death if, like most Britons of his day, he did not know how to swim. “It instantly struck me that they had a design to throw me over the pier-head…. There was not a moment to lose…. I darted forward. One of them, against whom I pushed myself, fell down…. And I escaped, not without blows, amidst their imprecations and abuse.”

The Blood-sweetened Beverage

Within two or three months of Clarkson’s return to London, where the committee had been energetically recruiting supporters and distributing books and pamphlets, there appeared a dramatic sign of a sea change in public opinion. There were no Gallup polls in those days, but there was one group of businessmen whose living depended on shrewdly gauging public tastes: the proprietors of London’s debating societies. (Sex was always popular, for instance, with debate topics such as “Whether the fashionable infidelities of married couples are more owing to the depravity of the Gentlemen or the inconstancy of the Ladies?”) After years in which slavery was only rarely a subject, abruptly the abolition of the slave trade was the topic of half of all 14 public debates on record in the city’s daily newspapers in February 1788.

At one, an ad promised that “A NATIVE OF AFRICA, many years a Slave in the West-Indies,” would speak. The anonymous African was probably Olaudah Equiano. Another newspaper reported “a circumstance never before witnessed in a Debating Society. A lady spoke to the subject with that dignity, energy, and information, which astonished every one present…. The question was carried against the Slave Trade.” Other than at religious meetings, these may be, scholars believe, the first occasions that either a black person or a woman gave a public speech in Britain.

The most important expression of public feeling came on great, stiff rolls of parchment. By the time Parliament adjourned for the year, petitions asking for abolition or reform of the slave trade had been signed by more than 60,000 people. Petitions were a time-honored means of pressure in a country where voters had no control whatever over the House of Lords, and where fewer than one adult man in ten could vote for the House of Commons. Anti-slave-trade petitions-never seen before-suddenly outnumbered those on all other subjects combined.

The superbly organized anti-slavery committee also pioneered several techniques used ever since. For example, they periodically printed copies of “a Letter to our Friends in the Country, to inform them of the state of the Business” — the ancestor of many a newsletter, print or electronic, published by activist groups today. They also agreed on a piece of text delivered to every donor in greater London appealing for another contribution, at least as big as the last. This may have been history’s first direct-mail fundraising letter.

When the famous one-legged pottery entrepreneur Josiah Wedgwood joined the committee, he had one of his craftsmen make a bas-relief of a kneeling slave, in chains, encircled by the legend “Am I Not a Man and a Brother?” American anti-slavery sympathizer Benjamin Franklin, impressed, declared that the image had an impact “equal to that of the best written Pamphlet.” Clarkson gave out 500 of these medallions on his organizing trips. “Of the ladies, several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair.” The equivalent of the lapel buttons we wear for an electoral campaign, this was probably the first widespread use of a logo designed for a political cause. It was the 18th century’s “new media.”

Within a few years, another tactic arose from the grassroots. Throughout the length and breadth of the British Isles, people stopped eating the major product harvested by British slaves: sugar. Clarkson was delighted to find a “remedy, which the people were… taking into their own hands…. Rich and poor, churchmen and dissenters…. By the best computation I was able to make from notes taken down in my journey, no fewer than three hundred thousand persons had abandoned the use of sugar.” Almost like “fair trade” food labeling today, advertisements quickly filled the press: “BENJAMIN TRAVERS, Sugar-Refiner, acquaints the Publick that he has now an assortment of Loaves, Lumps, Powder Sugar, and Syrup, ready for sale…produced by the labour of FREEMEN.” Then, as now, the full workings of a globalized economy were largely invisible. The boycott caught people’s imagination because it brought these hidden ties to light. The poet Robert Southey spoke of tea as “the blood-sweetened beverage.”

Slavery advocates were horrified. One rushed out a counterpamphlet claiming that “sugar is not a luxury; but…a necessary of life; and great injury have many persons done to their constitutions by totally abstaining from it.”

The abolitionists pioneered another key organizing tool as well, and you have seen it. Rare is the TV program or illustrated book about slavery that does not show a detailed, diagramlike top-down view of rows of slaves’ bodies packed like sardines into a ship. The ship is a specific one, the Brookes, of Liverpool, and Clarkson and his colleagues swiftly printed 8,700 copies of the diagram, and it was soon hung on the walls of homes and pubs throughout the country. Part of its brilliance was that it was unanswerable: What could the slave interests do, make a painting of happy slaves on shipboard? Precise, understated, and eloquent in its starkness, it was the first widely reproduced political poster.

The First Political Book Tour

Uprisings of the oppressed have erupted throughout history, but the anti-slavery movement in England was the first sustained mass campaign anywhere on behalf of someone else’s rights. Sometimes Britons even seemed to be organizing against their own self-interest. From Sheffield, famous for making scissors, scythes, knives, razors, and the like, 769 metalworkers petitioned Parliament in 1789. Because their wares were sold to ship captains for use as currency to buy slaves, the Sheffield cutlers wrote, they might be expected to favor the slave trade. But they vigorously opposed it: “Your petitioners…consider the case of the nations of Africa as their own.”

Consider the Africans’ case as their own? Stephen Fuller, London agent for the Jamaican planters and a key figure in the pro-slavery lobby, wrote in bewilderment that the petitions flooding into Parliament were “stating no grievance or injury of any land or sort, affecting the Petitioners themselves.” He was right to be startled. This was something new in human history.

Meanwhile, something else feeding the country’s growing antislavery fervor was Olaudah Equiano’s autobiography, a vivid account of his life in slavery and freedom. At seven shillings a copy, it became a best-seller. For an extraordinary five years, he promoted his book throughout the kingdom, winning a particularly friendly reception in Ireland, whose people felt that they, too, knew something about oppression by the British. Equiano’s was the first great political book tour, and never was one better timed.

The slave interests were piqued. In the biggest slave port, the editor of the Liverpool General Advertiser bemoaned the “infatuation of our country, running headlong into ruin.” Pro-slavery forces now launched counterattacks. They bought copies of a pro-slavery book for distribution “particularly at Cambridge” (college towns leaned left even then) and printed 8,000 copies of a pamphlet about how each happy slave family had “a snug little house and garden, and plenty of pigs and poultry.” They sponsored a London musical, The Benevolent Planters, in which two black lovers, separated in Africa, end up living on adjoining plantations in the West Indies and are reunited by their kindly owners. But Britons dependent on the slave economy were worried. Some doggerel made the rounds in Liverpool: If our slave trade had gone, there’s an end to our lives / Beggars all we must be, our children and wives / No ships from our ports, their proud sails e’er would spread / And our streets grown with grass where the cows might be fed.

The slave interests’ tactics bore a fascinating resemblance to the way industries under assault try to defend themselves today. When, for instance, there were moves in Parliament to try to regulate the treatment of slaves, the planters hastily drew up a lofty-sounding code of conduct of their own and insisted no government interference was necessary. They considered other P.R. techniques as well. “The vulgar are influenced by names and titles,” suggested one pro-slavery writer in 1789. “Instead of SLAVES, let the Negroes be called ASSISTANT-PLANTERS; and we shall not then hear such violent outcries against the slave-trade.”

The Movement Deflected

In Parliament, slavery’s most colorful spokesman was the Duke of Clarence, one of the many dissolute sons of King George III. As a teenager, he had entered the Royal Navy and gone to the West Indies, where he was wined and dined enthusiastically by the plantation owners. He showered marriage proposals and cases of venereal disease on their daughters and thoroughly imbibed their attitudes. In his maiden speech before fellow members of the House of Lords in their red and ermine robes, he called himself “an attentive observer of the state of the negroes,” who found them well cared for and “in a state of humble happiness.” On another occasion, he warned that Britain’s abolishing the trade would mean the slaves would be transported by foreigners, “who would not use them with such tenderness and care.”

Parliament was, of course, where the ultimate battle over the slave trade had to be fought. As spokesman in the House of Commons, Clarkson had lined up William Wilberforce, a wealthy, diminutive member of Parliament from Yorkshire, widely respected for his piety and eloquence. Except for his lifelong opposition to slavery, Wilberforce was Clarkson’s political opposite. Where Clarkson was swept up by the radical currents of the age, Wilberforce feared democratic impulses, labor unions, rising wages, and women’s participation in political life. Nonetheless, the two men were good friends and worked together closely for nearly 50 years.

But before Parliament could act, there were lengthy hearings. Witnesses like James Penny, a former captain, made the slaves on the middle passage sound almost like cruise passengers: “If the Weather is sultry, and there appears the least Perspiration upon their Skins, when they come upon Deck, there are Two Men attending with Cloths to rub them perfectly dry, and another to give them a little Cordial…. They are then supplied with Pipes and Tobacco…. They are amused with Instruments of Music peculiar to their own country…and when tired of Music and Dancing, they then go to Games of Chance.”

Rounding up eyewitnesses willing to speak against the trade was as difficult as finding military or corporate whistleblowers today. For a seaman or ship’s officer to testify critically meant he could never find work on slave ships again. At one point Clarkson rode 1,600 miles in two months, scouring the country for more witnesses. Often, he complained, “when I took out my pen and ink to put down the information, which a person was giving me, he became…embarrassed and frightened.” The most dramatic witness had just returned from a slave voyage: James Arnold, the Bristol doctor whom Clarkson had persuaded to keep a journal.

The slave interests skillfully used the hearings as a delaying tactic, spreading them out over several years, and outmaneuvering Wilberforce, who was a naive and disorganized legislative strategist. They beat back several of his attempts to get Parliament to abolish the slave trade, but by the spring of 1792, some five years after that first landmark meeting at 2 George Yard, it looked as if public feeling against the trade was too strong to be resisted. “Of the enthusiasm of the nation at this time,” wrote Clarkson, “none can form an opinion but they who witnessed it…. The current ran with such strength and rapidity, that it was impossible to stem it.” Exhausted, he had just finished one of his horseback organizing marathons around the country; Equiano was finding friendly audiences wherever he went; and the sugar boycott was at its peak. William Wordsworth wrote that the anti-slavery fervor of that spring was nothing less “than a whole Nation crying with one voice.”

Clarkson and other activists lobbied members of Parliament with unrelenting intensity. Anti-slavery petitions flooded Parliament as never before. When unrolled, the one from Edinburgh stretched the entire length of the House of Commons floor. Twenty thousand people signed in Manchester-nearly one-third of the city’s population. Petitions from some small towns bore the signatures of almost every literate inhabitant. Altogether, there were 519 petitions from all over England, Scotland, and Wales.

Four petitions arrived in favor of the trade.

The hearings for now finished, the parliamentary debate ran through the night. And so we must imagine the House of Commons chamber dimly lit by candles in a chandelier and wall brackets; the gowned, bewigged Speaker in his pulpitlike chair; members bowing to him when they leave the floor; the black-cloaked clerks below him; the snuffboxes at the doors; the candlelight glinting on the silver-and-gold ceremonial mace lying upon the central table; and, rising into the gloom, the benches of members, many in boots and spurs. The narrow visitors’ galleries high above them were packed, and newcomers were turned away. Equiano got there in time, however. Clarkson slipped a doorkeeper a handsome 10 guineas to let in 30 abolitionists.

When Henry Dundas, the politically powerful Home Secretary who controlled a large block of Scottish votes, rose to speak, no one knew where he stood. Dundas began by declaring himself in favor of abolition, at which those in the gallery must have felt their spirits rise. He then went even further, and declared himself in favor of emancipation of the slaves…but far in the future, he added quickly, and after much preparation and education. Then, to the abolitionists’ dismay, he introduced an amendment that inserted the word “gradually” in Wilberforce’s motion to abolish the slave trade. This signaled the moment that comes in every political crusade, when the other side is forced to adopt the crusaders’ rhetoric: The factory farm labels its produce “natural”; the oil company declares itself environmentalist. Dundas had called himself an abolitionist, but he asked that abolition be postponed.

The tall, slender prime minister, William Pitt, not yet 33 years old, spoke last, at 4 a.m. He declared himself “too much exhausted to enter so fully into the subject…as I could wish.” But to read his speech today is to feel shame at the sound-bite political rhetoric of our own time. Pitt spoke for more than an hour, extemporaneously. He began by taking the “gradualists” at their word, that they favored abolition, and then one by one showed how each of their points was a better argument for ending the trade now. Then he demolished the classic arguments of the slave traders. Like arms exporters today, British shipowners claimed that if they ceased carrying slaves, the business would merely go to other countries, especially the great rival, France. But how could anyone expect France to increase its slave trading when it was desperately trying to put down a vast rebellion-the Haitian revolution-in its prime colony? And as for the trade itself, Pitt asked, “How, sir! Is this enormous evil ever to be eradicated, if every nation is thus prudentially to wait till the concurrence of all the world shall have been obtained?”

Finally, Pitt made a grand historical comparison that cleverly made use of the country’s imperial arrogance. Britain, he declared, and British laws and achievements, were the acme of human civilization. But was it fair to call Africa barbarous and uncivilized, and to say that the slave traders were doing no harm by removing people from that continent? For in Britain, too, many centuries earlier, one would have found slavery and human sacrifice. “Why might not some Roman Senator…pointing to British Barbarians, have predicted with equal boldness, ‘There is a people that will never rise to civilization’…?” Legend has it that just as he concluded, the first rays of the rising sun burst through the large window behind the Speaker’s chair.

Pitt’s eloquence was not enough. The gradualist proposal passed, and after more debate the House set 1796, four long years hence, as the year when the slave trade was to end. A far more significant obstacle, however, was the House of Lords, which voted down any abolition at all, gradual or otherwise. The abolitionists were deeply discouraged. Nonetheless, for the first time anywhere in the world, a national legislative body had voted for an end to the slave trade.

“My Children Shall Be Free”

Before the issue could come up again at the next year’s parliamentary session, Britain and France went to war-a conflict that lasted, with only two short interruptions, for 22 years, ending only at Waterloo. The fighting brought with it a wave of repression: Every progressive movement, including abolition, was stopped in its tracks. It was not until 1806, after Clarkson, his hair now turning white, had toured the country rallying the faithful again, that the abolitionists found a way of cloaking a partial slave-trade ban in patriotic colors. Despite the war, British-owned slave ships, it turned out, were stealthily but profitably supplying slaves to French colonies. Parliament swiftly forbade this, and with the momentum from that move, the abolitionists were able to get both houses to ban the entire British slave trade in 1807.

They were still confident that this would soon spell the end of slavery itself. However, now that Caribbean planters were no longer able to replace slaves worked to death by buying shiploads of new ones, they eased working conditions and improved the slaves’ diet. By the 1820s, the slave birthrate was rising. In England, the movement came back to life, pushing now for emancipation. Once again, in his 60s, Clarkson headed off around the country, traveling for more than a year all told, visiting his contacts from decades before-or, more often, their children-and helping to start more than 200 local committees. With their eyes again on a very conservative Parliament, he and his colleagues were cautious, advocating freeing the slaves in slow stages.

But this time something different happened. More than 70 “Ladies'” anti-slavery societies sprang up throughout Britain; influenced by a fiery Quaker pamphleteer named Elizabeth Heyrick, they mostly pushed for immediate, not gradual, freedom. One woman activist wrote, “Men may propose only gradually to abolish the worst of crimes, and only mitigate the most cruel bondage, but why should we countenance such enormities…?”

When news of the revived movement crossed the Atlantic, at the end of 1831, it helped ignite the largest slave rebellion ever seen in the British West Indies. More than 20,000 slaves rose up throughout northwestern Jamaica. Planters had long liked to build their grand balconied homes on breezy heights, and, now going up in flames, they acted as signal beacons. As the militia were closing in on one plantation in rebel hands, a slave set fire to the sugar works, shouting, before she was shot, “I know I shall die for it, but my children shall be free!”

By the time troops suppressed the revolt, some 200 slaves and 14 whites were dead. The gallows or firing squads claimed more than 340 additional slaves. However, the rebellion helped convince Britain’s establishment that the cost of continued slavery was too high. William Taylor, a former Jamaican plantation manager and police magistrate, testified before a parliamentary committee that the revolts “will break out again, and if they do you will not be able to control them…. I cannot understand how you can expect [slaves] to be quiet, who are reading English newspapers.”

After the most massive campaign of petitions and demonstrations yet seen, Parliament finally gave in. Nearly 800,000 slaves throughout the British Empire became free on August 1, 1838. On the sweltering night before, the Baptist church in Falmouth, Jamaica, hung its walls with branches, flowers, and portraits of Clarkson and Wilberforce. A coffin was inscribed “Colonial Slavery, died July 31st, 1838, aged 276 years” and was filled with chains, an iron collar, and a whip. An open grave lay waiting outside. Just after midnight, singing parishioners lowered the coffin into it. Slavery in the largest empire on earth was over.

Of the 12 men who had assembled 51 years earlier in the Quaker bookstore and printing shop at 2 George Yard, Thomas Clarkson was the only one still alive.

Changing the World

Though born in the age of swords, wigs, and stagecoaches, the British anti-slavery movement leaves us an extraordinary legacy. Every day activists use the tools it helped pioneer: consumer boycotts, newsletters, petitions, political posters and buttons, national campaigns with local committees, and much more. But far more important is the boldness of its vision. Look at the problems that confront the world today: global warming; the vast gap between rich and poor nations; the relentless spread of nuclear weapons; the poisoning of the earth’s soil, air, and water; the habit of war. To solve almost any one of these, a realist might say, is surely the work of centuries; to think otherwise is naive. But many a hardheaded realist could-and did-say exactly the same thing to those who first proposed to end slavery. After all, was it not in one form or another woven into the economy of most of the world? Had it not existed for millennia? Was it not older, even, than money and the written word? Surely anyone expecting to change all of that was a dreamer. But the realists turned out to be wrong. “Never doubt,” said Margaret Mead, “that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.”