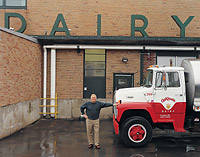

Photo: Russel Kaye

Around the state of Maine, it’s hard to miss Stan Bennett’s fleet of red-and-white trucks. They’re the ones with the Oakhurst Dairy logo emblazoned across the side and the Oakhurst guarantee (Our Farmers’ Pledge: No Artificial Growth Hormones) spelled out in big bold letters below. That pledge is printed on every carton and jug of milk that family-owned Oakhurst, Maine’s largest dairy, sells. And Bennett, who has spent the last decade inducing Maine dairy farmers to “swear off the needle,” as he puts it, isn’t inclined to change the wording around one bit. “We state what we are trying to do, simply and honestly,” says Bennett, president and principal owner of the Portland-based dairy. “It’s my right — and obligation — to inform [customers] of the facts.”

These days, Bennett has been spending a lot of energy defending that position. Monsanto, the nation’s largest (and only) producer of recombinant bovine growth hormone, rBGH, doesn’t think that Oakhurst — or other dairies around the country that have put similar labels on their milk — has a right to tout its products as rBGH-free. Last summer, with Bennett poised to expand Oakhurst’s market into the Boston area, lawyers for the St. Louis-based chemical giant struck. The company sued Oakhurst for “deceptive” and “misleading” marketing, and asked a federal court to order that the Farmers’ Pledge be removed from the dairy’s labels, advertising, and trucks. Monsanto’s argument: The genetically engineered rBGH, which increases a dairy cow’s milk output by about a gallon a day, has already passed muster with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Oakhurst’s labels, contends Monsanto, might cause consumers to question the drug’s safety, even though the FDA has found that milk from cows injected with rBGH is the same as regular milk and that the hormone poses no human health risks. Oakhurst’s milk is the same as every other dairy’s, maintains Monsanto spokeswoman Janice Armstrong: “Milk is milk. There’s no scientist in the world who can tell them apart.”

Still, although the FDA approved use of rBGH a decade ago, the controversy over the safety and ethics of the drug has never completely gone away. Some food-safety experts continue to argue that more research is needed to determine, for instance, if a hormone found in elevated levels in the milk of rBGH-treated cattle promotes growth of tumors. Canada and the European Union have both banned use of rBGH based on concerns that animals injected with the drug are prone to more illnesses and, as a result, may require higher doses of antibiotics. John Nutting, a third-generation dairy farmer and Oakhurst supplier in Leeds, Maine, shares those concerns, which is a major reason he refuses to use artificial hormones. “If you forced a racehorse to run 20 percent faster, that horse would eventually break down,” he says. “It’s much like that with a cow [on rBGH].”

There’s no question that greater public concern about these kinds of issues would be bad news for Monsanto. The company has invested heavily in rBGH, spending $100 million on development and $150 million for a new production plant in Georgia. Posilac, its brand name for the drug, is now injected into roughly a third of the nation’s 9 million dairy cows. Since its introduction ten years ago, Posilac has become the top dairy-animal pharmaceutical in the United States, bringing Monsanto more than $1 billion in sales.

Oakhurst’s Bennett also sees the label dispute as a business matter. For him, it’s not only his right to free speech that’s at stake. It’s a question of whether Oakhurst, whose slogan is “The Natural Goodness of Maine,” can give its customers what they want — something he says has been a company hallmark since his grandfather bought the “two-buggy” dairy in 1921 and moved it to its current location near downtown Portland.

“I don’t know, or pretend to know, the science,” says Bennett, over the steady thud of milk-processing equipment. “I do know what our customers have told us they want to know.” And that is whether the milk they’re buying contains rBGH. “Maine’s a green state,” and artificial hormones are a “very big issue here,” adds Bennett.

Oakhurst purchases its milk from 90 independent dairy farmers across Maine, all of whom sign an affidavit stating that they do not inject their cows with rBGH. (That represents about a quarter of Maine’s remaining 400 dairy farmers.) In exchange for swearing off the drug, farmers are paid a premium of 20 cents per 100 pounds of milk, amounting to a total outlay for Oakhurst of almost $500,000 a year. Since Oakhurst added the Farmers’ Pledge to its labels three years ago, the dairy’s sales have climbed at a 10 percent annual rate. In 2003 Bennett expected the company’s 250 employees to end up processing more than 250 million pounds of milk, with Oakhurst’s sales topping out at a record $85 million.

Maine shoppers aren’t the only ones who like milk produced without artificial hormones. Across the country, dairies that sell rBGH-free milk have been doing a brisk business, according to Ronnie Cummins, national director of the Organic Consumers Association. And it’s not just selling at natural-foods stores or gourmet markets, but at mainstream convenience stores, too. “The market presence of rBGH-free and organic milk is at an all-time high,” says Cummins. “It’s no longer a niche market they’re messing with, and Monsanto’s in a panic.”

Monsanto’s suit against Oakhurst is not its first over the labeling issue. In 1994, the company sued dairies in Texas and Iowa that had also marketed their milk as rBGH-free. In both cases, the dairy owners agreed to change their labels, and Monsanto backed off the suits.

“If history’s any indicator, Monsanto likes to pick on smaller guys,” says Joseph Mendelson, legal director of the nonprofit Center for Food Safety. In Oakhurst’s case, Monsanto initially asked state officials in Maine to take action to halt the dairy’s marketing practices. But Maine officials refused. Oakhurst’s labels “do not constitute health claims of any sort,” Maine attorney general G. Steven Rowe wrote early last year in response to Monsanto’s request. They simply allow the consumer “to make an informed decision.”

When that tack failed, Monsanto decided to handle the matter itself — and Bennett believes it was no coincidence that the suit was filed this summer, just as Oakhurst was getting set to expand into the Boston market. Bennett is going ahead with his expansion plans in spite of the lawsuit. Since the suit was filed, he says he has gotten hundreds of letters of support from around the country.

In Portland, milk buyers are doing their part for the hometown underdog. At a Shaw’s Supermarket one day in October, shopper Maria Hanley reached into the dairy case and went straight for a half-gallon of Oakhurst 2 percent. Asked why, Hanley had a ready answer: the lawsuit. “Here’s a big company pushing around a little guy,” she said. “I want Oakhurst to survive.”

That kind of support has made Bennett more determined than ever not to budge. A minor adjustment or two, such as a quick mention of the FDA’s approval of rBGH on Oakhurst’s labels, would likely be enough to appease Monsanto and end the suit. Bennett, though, is standing by his Farmers’ Pledge. “I’m not a crusader, but we needn’t compromise,” says Bennett. “We’ll see this through to the end.”