In early 2003, Deb Mayer, a teacher at Clear Creek Elementary School in Bloomington, Indiana, led a class discussion based on an issue of Time for Kids, which included an article about planned peace marches against the upcoming war in Iraq. Discussing Time for Kids articles was part of the school’s regular curriculum. A student asked Mayer if she would ever particpate in a peace march, and she replied: “When I drive past the courthouse square and the demonstrators are picketing, I honk my horn for peace because their signs say, ‘Honk for peace.'” She said she thought “it was important for people to seek out peaceful solutions to problems before going to war and that we train kids to be mediators on the playground so that they can seek out peaceful solutions to their own problems.”

That turned out to be a big mistake. According to Mayer, one of her students told her parents that she was encouraging people to protest the war. The girl’s father, calling Mayer unpatriotic, called the school and complained. A conference was held, and the father yelled at Mayer, “What if you had a child in the service?” It turns out Mayer had a son in Afghanistan, but that did not settle the matter. The father insisted that Mayer not mention peace in the classeroom again, and the principal agreed to make sure she did not.

The principal then cancelled Clear Creek Elementary’s Peace Month, and sent a letter to Mayer, telling her to refrain from expressing her political views. At the end of the semester, the school did not renew Mayers’ contract. Affidavits were allegedly gathered from parents which criticized Mayers’ teaching style, and an accusation, which Mayers denies, was made that she continued to talk about peace after being told not to.

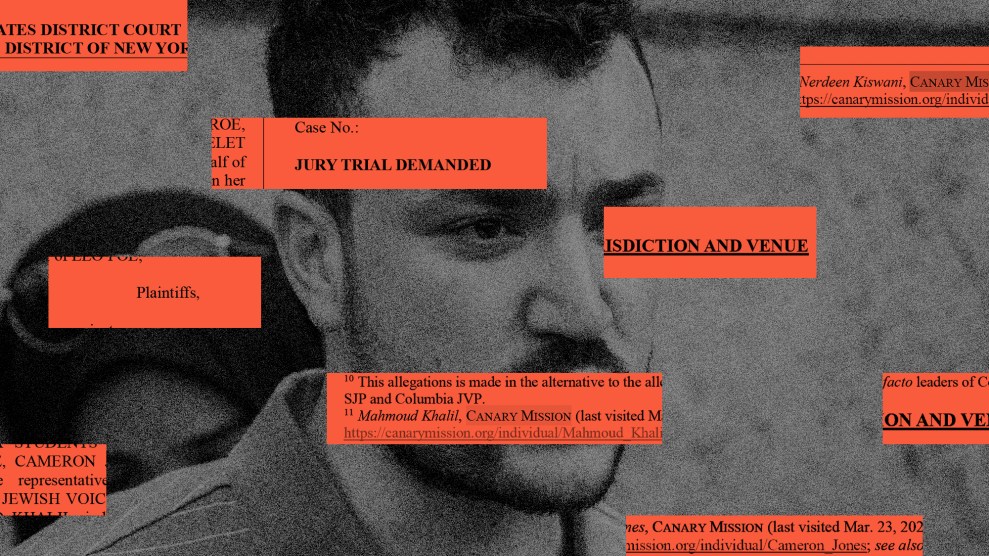

Mayer sued the school district, on the grounds that the termination was retaliation for expressing her opinion, and that the school had violated her free speech rights. The school maintained that:

Ms. Mayer’s speech on the war was not the reason for her ultimate termination. Instead . . . the motivating factor for her termination was her poor classroom performance, the ongoing parental dissatisfaction, and the allegations of harassment and threats towards students.

Mayer’s attorney says that the parent affidavits were signed in 2005, two years after his client’s termination, and therefore could not possibly have been used in the decision to terminate her contract. In addition, the attorney cites an excellent evaluation that had been given to Mayer.

Earlier this month, Judge Sarah Evans Barker dismissed Mayer’s case, saying the school district was within its rights to terminate her because of complaints from parents about her performance in the classroom. According to Barker,

…school officials are free to adopt regulations prohibiting classroom discussion of the war…the fact that Ms. Mayer’s January 10, 2003, comments were made prior to any prohibitions by school officials does not establish that she had a First Amendment right to make those comments in the first place.

The judge also suggested that Mayer, by making her comments, was attempting to “arrogate control of the curricula.”

Though it may be true that a school has a right to restrict certain speech by teachers, the Mayer case is full of holes. There is no proof other than mysteriously appearing after-the-fact “affidavits” that anyone was concerned about the quality of her teaching, yet there is contrary evidence that she was doing a good job. Furthermore, Meyer spoke only in the context of answering a student’s question about standard curriculum content.

Mayer says she has lost her house, her health insurance, her life savings, and her job prospects.