VAN HORN, TEXAS. Fifteen thousand vehicles a day roll alongside this frayed ribbon of a town off Interstate 10 in the high desert of West Texas. Some of their drivers pull into truck stops or one of about a dozen motels for the night. Some carry transients, dumped here to look for work that won’t be found. Every day, Greyhound spills out its rumpled travelers for a stretch, a smoke, or empty calories before returning to what’s called America’s loneliest highway, 2,460 miles of blacktop that can lead a soul from Santa Monica, California, to Jacksonville, Florida, and, if he or she pauses here, maybe to God.

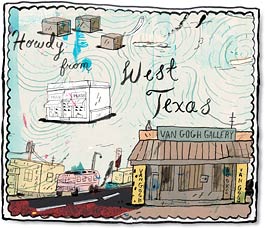

Nine years ago, Ran Horn, 53, came along this road via a few others from Duluth, Minnesota, where he’d been a Baptist preacher until he fell 30 feet from a church scaffold and landed on his head. “Well, this has been a fun life, hasn’t it?” he remembers thinking as the concrete beckoned, except he didn’t die and wasn’t even hurt too badly aside from the crack in his skull and a gash along the side of his face that plastic surgeons managed to mend. But it was his Damascus Road, the end of life as he’d known it. Later, noticing a shop selling machine prints of Old Masters at the Mall of America, his epiphany was complete. “I can do that!” he said, “only with real oil paint, on real stretched canvas.” He didn’t know much about painting. Apart from an intricate paint-by-number kit and some elementary tips from television’s anyone-can-be-an-artist guru Bob Ross that he’d picked up in the idle hours in front of the tube as a prison guard, Horn had no background. He knew what he liked, though. Vincent Van Gogh became his teacher, spiritual guide, and subject. Working almost entirely from pictures and Vincent’s letters, Horn taught himself about color, light, and composition by doing “knockoffs” of his hero’s masterpieces, then began variations on the theme, composites of Van Gogh images, and scenes of his own quirky invention. Like the master, who’d once been a missionary among coal miners in Belgium, he abandoned the conventional ministry for good, assumed a life of poverty, and because “the unfortunate thing about it is that as an artist you do have to run a business,” two years later packed up his family and moved to where rent was cheap, weather was fine, and the road supplied customers and a catchy handle: Ran Horn of Van Horn runs the Van Gogh Gallery by the roadside.

In a sense, Ran Horn had come home. He was born and raised 163 miles northeast of here, in Odessa, “the ugliest town in the world,” he says, borrowing from Larry McMurtry, flat and brown, with oil works rather than the far fringe of hard, Mars-like mountains that give Van Horn and the landscape south of it along U.S. 90 a proud bleakness. He didn’t know when he came here, setting up a gallery cum junk shop, used book store, and studio—a reliquary of ordinary things and magical offerings, dirt and dogs and bright varnished canvases, his own “little grotto” made “gaudy as hell” as an enticement to commerce—that 74 miles south, in the town of Marfa, the official art world had established its own true church.

Almost 60 years ago Donald Judd passed through these parts on his way to Korea, and was so awed by the sweep of light and land that in 1973, by then a famous sculptor sick of the New York gallery scene, he returned. In Marfa he drafted specifications for the fabricators of his pieces and collected real estate: the old Wool and Mohair Building in the center of town, a former ice factory, many main street buildings, a 340-acre derelict Army base, associated hangars, and the quartermaster’s house. For 20 years he worked converting these, particularly the base—which was first used during the Mexican Revolution as a cavalry post, then as a World War II camp for German POWs—to house permanent installations by himself and his friends, in the process creating spectacular frames for the landscape. Though initially assisted mightily by New York’s Dia Art Foundation, Judd regarded himself a renegade from the art world. Then he died, leaving believers to answer the question reportedly seen on bumper stickers on out-of-state cars in Marfa: “WWDJD?” or What Would Donald Judd Do?

In an office of the Chinati Foundation, one of two nonprofits that manage Judd’s properties, someone has painted “truth” in large letters on a wall. Visitors assembling for the guided tour at the old Army post may purchase Judd’s Complete Writings or lesser texts, along with postcards and vestments. The tour begins at a pair of glass-sided artillery sheds that hold Judd’s 100 aluminum boxes of identical size but individual configuration. Upon entering, pilgrims may touch a representative aluminum square. Hands reach out, voices lower: How smooth, how cold, heavy too. In summer these sheds will be 100 degrees. Two POW-era stencils on the wall have been preserved: “ZUTRITT FÜR UNBEFUGTE VERBOTEN,” which our guide translates as “Unauthorized persons are not allowed to enter”; and another that means, “It’s better to use your head than lose it.” She leads us through 14 installations on post, a Via Dolorosa, with the sparest instructions. The works we are about to see are extremely fragile. We must not touch, not get too close; even our breath may damage them. We follow narrow paths, up stairs then down, then up again, 12 times, to see the light of Dan Flavin. Only five can enter at a time to view Roni Horn’s (no relation) solid copper truncated cones, each, we’re told, weighing exactly 2,250 pounds. At the former gymnasium turned dressage arena turned exhibition space/banquet cathedral, the center space of gravel and concrete strips is exactly double the width of the two concrete platforms on either end. A courtyard off the grand hall features a bath, but it is dry. A small room holds dozens of candles and vessels for the rare nights when suppers are held at the long tables. All the virtues of Chinati are contained within the arena. It is pure and clean and balanced. It has no place for sin. The last stop on the tour is an installation of Carl Andre’s poetry, words from our language scrambled in a Babelogue.

“Maybe the best thing you can tell an artist is ‘Cut your tongue out,’” Ran Horn suggests to me back at his place. “There’s the art, and let it speak for itself.” He says that when someone looks at his pictures he can feel if he’s communicating. “It’s like a tuning fork,” and if not, “that’s okay too.” He has never been to Chinati, though if he had the gas money, a spare day, and $10 he wouldn’t mind seeing it. He knows the art there is called minimalism, though Judd never liked the term. Vincent is called a post-impressionist, but Horn thinks that’s wrong. “Vincent was a maximalist, and I’m a maximalist.”

How much can you fit into one painting, into one life? Horn wouldn’t go to art school even if he could afford it because after seminary and nearly 27 years of conservative sermonizing, he’s cool to doctrine. That was the other part of his epiphany: “I don’t know a real Christian,” he says; doesn’t think he was much of one himself, rigid at the pulpit. Outside and in the shop, hand- painted signs declare: “Jesus Is Pro-War, Pro-Rich & Pro-Republican—Not!” and “Blessed Are the Warmongers (Gehenna 6:66).” When visitors mix it up with him about politics or religion, he’s as apt to preach Tolstoy as Jesus. Some people come in asking for jobs; some, traveling musicians mainly, tell him Vincent is their patron saint because they know about pain; after the vice president shot a man, someone came in just to ask if Texas really requires a license to hunt quail. “America comes to me on the Interstate,” Horn says. Most buyers who aren’t looking for a book or bit of junk take away a Vincent knockoff, signed by Horn, who doesn’t believe in forgery. Original pictures he won’t sell for any price, though he has done knockoffs of himself for some customers and is now making machine prints.

Recently, the local development corporation here held a seminar on art and economic growth, but Van Horn is emphasizing training and education to spur resident-run small businesses. People don’t want to become an “arts community.” They hear the talk from Marfa, a charming place where real estate prices have risen sixfold in five years but a third of residents are poor, where tax-exempt arts centers are so common that the pizza joint named itself Pizza Foundation, where a cavernous bookstore/café sells coffee for $12.95 a pound, and where people can walk a block to a gallery but must drive 26 miles to fill a prescription.

Last October a couple of artists sponsored by a Marfa nonprofit installed what they called Prada Marfa in a stark adobe structure on U.S. 90 about midway to Van Horn, outside the town of Valentine, which recently lost its last store. The shelves were adorned with 2005 collection shoes and bags, and the door was sealed. The artists said they hoped Prada Marfa would become “a ruin.” Two days after the opening, vandals smashed the window, stole the shoes and bags, and wrote “DUMB” in big letters on the side of the building. A Marfa teenager called Alberto told me he was sorry he didn’t strike first.

The swiftness of the ruination wounded rather than elated the artists, who are avowedly “interested in gentrification processes.” Prada supplied more merchandise, and this time the artists cut the handbags’ bottoms out. White and gleaming once again, the installation now has a security system. Some years back, a local woman asked Ran Horn to duplicate a picture of zebras done in the motel modern style—weak lines, pinkish sky, offensively inoffensive.

Later a burglar of opposing tastes slashed the painting, and she returned it. Horn found three toy guns and inserted them in the cuts. Today it looks as if the herd is running unawares at sunset to its doom.