Photographs By: Kevin Patterson

it’s late january, and on my way to Kandahar I stop at a facility called Camp Mirage that sits on a clear desert highway and shimmers in the early afternoon heat. It serves as the support base for Australian, New Zealand, and Canadian forces in Afghanistan and the Persian Gulf. The camp exists, and yet officially does not: The Host Nation does not acknowledge it, forbids its mention publicly. Uniforms must not be worn off the base, nor may taxis be hired to bring personnel back from shopping trips in the closest city. Soldiers who’ve served their six-month tours and are at Mirage awaiting flights home affect postures of world-weary and taciturn indifference, while the 19-year-olds coming in gaze around slack-jawed.

Thirteen years ago, I was a captain in the Canadian army, a medical officer in an artillery regiment, and bored to the point of catatonia. I had enrolled for a tour of duty partly in an effort to pay for medical school, but I was also drawn to an entirely fantasized idea of distant deployments and U.N. peacekeeping, anything to get me out of dusty and predictable Manitoba, where the idea of exotic exists only in the context of dancers in Saturday-afternoon bars. As it turned out, I was attached to a base in Shilo, Manitoba, a vast, windswept expanse of whitewashed clapboard huts tossed up during World War II. I was 25 when I arrived there, and had 400 young men and a small clot of aggrieved women to care for. They were none of them sick. If any one of them had anything in the way of important illness, they would have used it to insist on a posting to a city. My day’s work was done by 9 a.m. The rest of the day, I napped on my desk. Little puddles of drool accumulated beneath my chin.

Today, after years of sitting on their hands in Kabul, the nato-led International Security Assistance Force (isaf)—especially Canadian, Dutch, and British forces—has moved into the southern provinces of Uruzgan, Helmand, and Kandahar to wrest control back from the Taliban. For Canada, which closed its last military hospital in 1998, it is like nothing since Korea. It quickly became clear that uniformed personnel were too few to staff the Canadian-run combat surgical hospital at Kandahar Airfield. An appeal was put out for help. Within a few months, several nurses and doctors with whom I work on Vancouver Island had all signed up for brief rotations for the Kandahar icu. I did too.

Is There A Doctor On The Base?

10,853 U.S. physicians and dentists served in Korea, fewer than half via the “doctor draft.”

30,000 U.S. physicians and dentists served in Vietnam. Only 100 had been drafted.

Today, the U.S. Army has 4,200 physicians on active duty worldwide.

There are 32 active U.S. military doctors serving the 25,000 U.S. troops in Afghanistan.

There are 96 physicians, 18 general surgeons, and 9 orthopedic surgeons serving the 146,000 U.S. troops in Iraq.

The U.S. Army has 2 pediatric surgeons.

20 children are seen at the Bagram Air Base hospital in Afghanistan each month.

The U.S. National Guard is offering health care professionals $30,000 in bonuses for three-year commitments.

Canada offers medical officers enlistment bonuses of up to $225,000.

—Nicole McClelland

I board the C-130 Hercules along with soldiers from the 2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment. There’s an air of taut and humorless anxiety I do not recall from my own days in uniform. I wear a Kevlar helmet and body armor over my jeans and sweater. The other two civilians aboard are an agitated bouffant-going-gray foreign-service officer and a lithe goateed man who, when I ask him what is bringing him to Afghanistan, replies, “this and that.” He could be a hairdresser or software engineer but for a certain exaggerated yet quiet intensity. He says his name is Greg. The foreign-service officer asks him how long he will be in Afghanistan. “Two, three months,” he says. She nods, and begins telling animated and self-congratulatory stories of her last spell in Kabul. He listens but doesn’t pay her much attention.

Three and a half hours later we begin our descent into Kandahar Airfield, a giant base from where isaf coordinates its attempts to control southern Afghanistan. It is from Kandahar that the Taliban first emerged in 1994 and where it finds succor today. Kabul is now almost safe: Girls go to school; the markets are full. In Kandahar, where the cloak of the Prophet is kept, bicyclists explode themselves next to soldiers trying to build roads.

After landing, we’re ushered into a devastated hangar, where tendrils of aluminum roof sheeting hang down like crepe paper; Mars glows red between the largest of them. A company sergeant major approaches and asks who I am. “Well, why hasn’t the hospital sent someone for you?” The foreign-service officer walks around in tight, quick circles asking pointed questions of her BlackBerry. “Greg” has slipped away quietly. Detecting little in my bewildered response to satisfy him, the sergeant major barks into a telephone. A few minutes later a medic arrives to drive me to the hospital. Nobody naps on his desk here.

past midnight, I’m deposited in my barracks and meet the other doctors: a mix of Dutch, British, and Canadian officers, as well as a Canadian civilian radiologist, and the icu doctor I’m replacing, John Ronald, with whom I work on Vancouver Island. After a burst of enthusiastic welcome, words run short. I’ve been flying for days. I crawl under my coarse woolen blanket. An instant later, I wake myself up with my own snoring.

The next morning, John shows me around the recesses of the jury-rigged hospital, part tent and mostly unpainted plywood. The toilets are in a prefab metal container. There are two operating rooms and the only ct scanner in the entire province. Within this construction-site ambience work two surgical teams: one Canadian, the other Danish or Dutch, which alternate every two to four months. Also present: British, Australian, and American doctors, nurses, and medical assistants; morning rounds have the sort of internationalist air that Madrid might have had in 1936. ncos don’t bother saluting officers here—no one can figure out the myriad of rank insignia present on the base.

A few months earlier, John tells me, the fighting was ferocious in Kandahar, but it always stalls in winter. The plain outside Kandahar in late January is dusty and, come midday, even warm. But in the mountain passes leading from Pakistan, the snow is deep, deep, deep. This makes for difficulty if one is crossing into Afghanistan, and comparatively gentle days in Kandahar.

Nevertheless, by the end of my first week, I scrub in on nerve and vascular grafting procedures, craniotomies, and all manner of thoracic surgery. If bones are involved, the orthopedists wade in; the oral surgeon does any procedure north of the collarbone. Otherwise, the general surgeons demonstrate just how general they can be. There are no plastic surgeons available for burn patients, no pediatric surgeons for the kids, no urologists, no vascular surgeons. It’s clinical practice as it exists in places remote either in geography or time. But in medicine, as in love, there is Doctor Right, and there is Doctor Right Here.

About two-thirds of our patients are Afghans: Taliban and Afghan National Army (ana) personnel and civilians. The rest are coalition soldiers. The coalition folks generally do well; their body armor is very effective, and the amount of penetrating chest and abdominal trauma is limited. Not so with the Afghans. They often don’t have body armor, and they aren’t eligible for evacuation. When we received news that a mass casualty was en route with severe burns, we were told not to intubate Afghans with burns over more than 50 percent of their bodies—because in the absence of a burn unit, such a patient requiring life support rarely survives—but that we should do everything possible for coalition personnel because they would be evacuated to Germany or Dubai and then to places like Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, where the burn care is the best in the world. Any temptation to protest the different valuation of life explicit in the order was stalled by the briefest survey of the country around us: What else is new?

ten thousand soldiers and civilians work and live at Kandahar Airfield. The civilians mostly work for kbr, the former Halliburton subsidiary that runs the dining facilities (dfacs) and maintains the miles of prefabricated, pressed-metal barracks. The contractors speak with Midwestern and Southern accents mostly, chatting merrily with soldiers like neighbors leaning over a fence. The few other civilians include a handful of physicians, some foreign-service personnel, and—judging from the haircuts and eyewear—some cia types. It becomes a game to spot Special Forces soldiers, who do not wear uniforms but are revealed by their shoulders, exuberant beards, and sun-wrinkled eyes.

In the dining halls, Australian, New Zealand, and Jordanian soldiers eat alongside soldiers from nato countries, one polyglot mass of blinking and farting martial vigor. Viewed from the entrance, the long rows of tables appear as a kind of fabric mosaic: The Americans and Canadians in their pixelated browns and grays, the Australians in their bunny-ear-patterned beige, the British streaked by sawgrass-colored fronds, and the Romanians in yellowish-brown uniforms and floppy hats—currently the trend in military millinery, the Canadians, Dutch, and British all sport variants—looking rather like lifeguards in mufti.

Soldiers may not be fed if they are unarmed—though neither are they permitted entry if they are carrying a bag of any sort. I ask a soldier waiting in line with me for breakfast why this is. “In case a Taliban in disguise,” he nods toward one of the Jordanians, “wants to blow us up.” He suggests I stuff my camera bag in a jacket pocket. In line ahead of us is an American private from the perpetually deployed 10th Mountain Division carrying an M203 grenade launcher; in front of him the Jordanians stand in jungle-green fatigues, AK-47s slung casually over their shoulders, magazines jutting from their pockets.

The Romanians, who help provide airfield security, have quickly acquired a reputation for both aggressive patrolling and a certain erratic quality to their response times. Opinions vary over which characteristic predominates. Again and again, I try and fail to engage Romanian soldiers in conversation, but they keep to themselves. They’ve built a little church that appears to have been lifted whole from the shore of the Black Sea. On New Year’s Day, Romania joined the European Union, and their presence in Kandahar can be explained both by the application to join and the expectation that it would be accepted. Everyone comments on how much the Romanians eat—great, heaping mounds of chicken and potatoes and steaks stacked like flapjacks. Still, their comparatively gaunt faces seem half the size of their corn-fed brethren, dark eyes under shaven heads gazing around at such foreignness. And all the food you can eat.

i am standing at the memorial to the 43 dead Canadian soldiers when the first rocket flies into the camp. A granite slab with Captain Nichola Goddard’s picture etched into it smiles out from among the others. She was an artillery officer from Shilo, my old regiment, working as a forward observation officer (who directs the fall of artillery shells) when she was killed by a rocket-propelled grenade (rpg). Orthopedic surgeon Steve Masseours—we’d both been captains in Ottawa a dozen years earlier—is standing beside me. He’s a major now, and was on duty when Goddard came into the hospital, in May 2006. “She had terrible luck,” he says. “Fragment of shrapnel flew in under her helmet, over her armor, at just the wrong angle, and went into her head.” She was the first female Canadian soldier killed in action in Afghanistan. Twenty-six years old. Horsey, good-natured grin. Almost beautiful. Beautiful, in fact. “We started to resuscitate her, but it was pretty clear it was hopeless,” Steve says.

Just then, a rocket whistles overhead, a short, thin stream of red light trailing behind it. Steve is already ducking low when it explodes in the military police compound, a hundred yards away. A fraction of a second later, another. As the attack siren goes off, we lie on the concrete pad among the pictures of the fallen—smiling, large-toothed men and one woman self-conscious in their posed portraits; the common elements: shoulders and acne. After a few minutes, we scurry over to the nearest bunker, joined by a nervous clot of newbie soldiers from Canada and Holland, and Americans, who do 12- to 15-month tours and were long ago inured to such attacks. “That’s the helicopters going up,” one lanky Texan says, to the thumping sound filling the air. When it is next possible to be heard, he adds, “Give them 30, 45 minutes and y’all can go back to work.” The Texan describes how the rockets are triggered when a block of ice holding down the release lever melts—leaving the Taliban time to get many miles away before the helicopters find the launch site. I nod more times than is necessary. He is entertained. The all-clear signal rings out and we walk quickly to the hospital. There is only one wounded—an American MP who was picked up and tossed by the explosion.

A little later, we eat with Major Sanjay Acharya, an anesthetist of Gujarati stock by way of Newfoundland who speaks with the rolling lilt of that island, almost Irish in its gregarious musicality. “What this represents, gentlemen,” he declares, indicating the salmon on his plate, “is creeping mediocrity.” Island peoples have high standards for fish, but Acharya also allows he’s rattled by the rocket attack. “Bastards are probably off giggling like it’s some fucking game of Knock Knock Ginger.”

At home, in Ottawa, Acharya keeps workaholic hours—more than 120 on-call nights a year in critical care and anesthesia. Here, he sleeps heroically when the wounded are not coming. When upright, he lays out his plans: to start a cult modeled on Scientology—”I’ve already got that Eastern mystic-yogi-guru thing down”—to attend law school, to leave the military as soon as he’s eligible for his pension. In an organization committed to the cultivation of zeal, he has proved barren land. He tells us he once dodged a court-martial (he had irritated his superior into apoplexy) by simply failing to cooperate, give a statement, or use the military-appointed lawyer. The functionaries, it is plain, would only ever be baffled by him. The nameplate on his room reads, “G. Assman.”

by valentine’s day spring is unfolding; this is pleasant, in that the rain has stopped and one can sit in the sun and read, but it causes some foreboding. Musa Qala, about 100 miles northwest of Kandahar in Helmand Province, has recently been seized by Taliban forces in defiance of a mutual-withdrawal agreement made earlier with the British. Today the British killed the Taliban commander with an aerial strike. Helmand looks to be this year’s hot spot, where the British have just launched Operation Kryptonite, aimed at seizing control of Kajaki Dam, a major power source that has been off-line since 2003. There have been hundreds of Taliban casualties in the previous six weeks—a fact we can learn from Google News. But the bed censuses at the coalition hospitals tell the story just as well: The British-run Camp Bastion field hospital in Helmand is constantly in condition red, and the overflow casualties are coming to us.

administered with the help of the Red Cross, the Mirwais Hospital in Kandahar City will take any civilian or Afghan National Police (anp) officer initially treated by us, but it won’t take Afghan soldiers. The Taliban have threatened Mirwais doctors who’ve come to our base for clinical mentoring, and they worry that if they assist ana soldiers, their hospital will be attacked. At the Afghan military base Shir Zai, a facility the U.S. military built to be the provincial ana hospital has been sitting empty, much to the frustration of a U.S. naval officer who’s been laboring to open it. Unused crates of equipment and ct scanners sit in the building, she says. We meet with the Afghan brigade surgeon responsible for the Shir Zai hospital, an educated and committed man who has watched his physicians and nurses desert one after another, afraid and demoralized. “No one from the north, where it is safe and where their families are, wants to come here,” he tells us. “Kandahar has always been like this, far from Kabul and hostile to anyone from any other place.” He spots Acharya among us and addresses him in Dari. Acharya replies that he speaks only Gujarati. There is a moment of what I take to be silent commiseration: South Asians surrounded by farangis, which in both languages means foreigners.

like every saturday, today local merchants line up at the base gates before dawn and submit to body searches. By mid-morning they’ve set up a bazaar to hawk food, rugs, hookahs, and the relics of previous conflicts: piles of ancient British Enfield rotating bolt rifles (the colonial army left behind thousands) and Soviet army uniforms, many with carefully patched bullet holes. The object lesson could not be more clear.

Genuinely multinational combat armies are uncommon. Historically, one nation dominates an effort, and bit players stand around for show. Yet 37 nations compose the isaf, each with its own generals and political masters. Aberrations in codes and procedures can lead to friendly fire, though the U.S. military prefers the “blue-on-blue” appellation. Twice Canadian infantry have been fatally attacked by American aircraft. But far more common is coalition personnel firing on Afghan allies. A few days ago an Afghan soldier riding in a truck approached a Canadian military convoy from behind; he was recognized as ana by the rear vehicle and waved forward. This was not communicated to those in the lead vehicle, who opened fire, killing the driver and sending six rounds into the passenger’s evidently robust body armor and another into his right arm, breaking the bone and severing the ulnar nerve. We grafted his nerves, and in six months or so (peripheral nerves grow a millimeter a day) it will be possible to know if the surgery was successful.

Can doctors tell if fire is friendly or not? The infantry believes it should be easy to know: nato countries use 5.56 mm ammunition while the AK-47 favored by the Taliban uses 7.62 mm. Except local allied forces—the ana, anp—use AK-47s too, as do the forces of the former Warsaw Pact—the Romanians, the Estonians—and anyway, when bullets strike bone they can shatter, spraying shards of metal through the body like a satellite breaking up on re-entry. More often the full-metal-jacketed rounds go through and through, as they were designed to do. We can’t necessarily tell whether a wounded person was shot by his confederates or by an antagonist, except by what is claimed. Probably, more times than we could guess, we wouldn’t want to know the answer.

When an aeromedical team tells us they’re bringing in an ana soldier shot in the thorax, we wonder why they’re bothering—such patients usually die en route. But the shooter must have been at an extreme distance, for the bullet is palpable just under the skin over the sternum and excised under local anesthesia by Lt. Colonel Reeuvers, a Dutch surgeon. When he plucks out the AK-47 bullet, Reeuvers and his patient exchange amused grins. Reeuvers tells him to buy lottery tickets. A translator tries but both he and the patient look puzzled. “Go to the casino,” Reeuvers tries again. Still only baffled nods. Then the Afghan soldier leaves our base for his own, the question of who shot him unasked, unanswerable.

february 18: The CH-47 Chinook helicopter had 22 Americans—many of them Special Forces soldiers—on it when it crashed, apparently from mechanical failure, in the mountains of Zabul Province. Eight died on impact; 14 survivors were several hours in the snow awaiting rescue. The notification of a mascal, mass casualty situation, goes out long before they arrive, allowing us to buy coffee from Green Beans, a sort of downscale Starbucks that’s become as common on American military bases as its inspiration is in gentrifying urban cores.

The rescue helicopters bring the soldiers in by groups of three and four; they are all terribly cold, 29, 30 degrees Celsius, and shattered—fractured spleens, broken spines, punctured lungs, and broke-open pelvises. “Bone salad,” one doctor calls it.

Cold blood will not clot appropriately and so they bleed briskly—from minor wounds as well as major ones. The blood bank begins releasing the first of the 200 units of blood needed that day.

One young sergeant is unmarked but unconscious. A ct scan of his brain confirms hemorrhaging and severe swelling—traumatic brain injury. We start him on diuretics; it will be seven hours before the evacuation team can arrive, and then a seven-hour flight to Germany.

Another sergeant with an obviously broken femur insists his comrades be attended first. When an X-ray shows his right chest to be half full of blood, an American Special Forces surgeon appears from nowhere—I thought we were the only doctors in the camp—and puts a chest tube into the man’s thorax. The sergeant begins coughing blood and a Special Forces nurse anesthetist also appears; I ask him to intubate as I put in a second chest tube. The sergeant’s blood pressure still falls, so I start large central lines into his femoral veins to pump blood into him. His blood pressure drops further. I put a large needle into one side of his chest and then the other. Great plumes of blood-tinged air spurt from the needles: bilateral tension pneumothoraces—air building up around the heart until it can’t pump. The Special Forces surgeon and I look at one another quizzically. That shouldn’t happen with chest tubes in place.

The management of battle trauma has been changing quickly, the Special Forces surgeon tells me as we work on the man. He’s just spent a year in Iraq, doing trauma resuscitation full time. “We’re going away from crystalloid”—saline-based resuscitation fluids commonly used in civilian practice—”and we’re using larger volumes of blood products up front”—plasma, packed red blood cells, platelets, frozen concentrated fibrinogen, and recombinant Factor VII, an important clotting protein costing $5,000 a dose. “We’re also very aggressive about warming them, and we’re using fresh whole blood more and more often.” The practice of taking blood straight from on-site donors and running it into the wounded ended in civilian contexts in the 1950s—it was felt to be more efficient to separate blood into constituent parts and administer as required. But the lesson of Iraq, he says, suggests that fresh whole blood retains its ability to clot—crucial to trauma patients—far better than frozen, stored blood.

It’s not so surprising when put like that: Not many tissues work better after a month in the fridge. More striking, I think, working alongside him, is the way military medicine is not quickly or broadly generalized to civilian practice. The experts, it is generally felt, work at places like Harvard or the Cleveland Clinic. But who would know better how to take care of young people with blunt trauma or gunshot wounds than doctors in Iraq and Afghanistan?

We work the rest of the day resuscitating the crash victims. The man with the head injury deteriorates, his right pupil grows very large and unreactive, his pulse slows to 35. Four of us convene at the foot of his bed. Hours earlier, we discussed a decompressive craniotomy, a desperate measure with little data to suggest that it works. But now he is near death and no one can think of anything else. The oral surgeon takes him to the OR and begins drilling holes in his skull. As the skull flap comes off, the sergeant’s pulse rises and his eye begins to constrict again.

We’ve run out of frozen concentrated clotting proteins, so the Americans activate their walking blood bank—soldiers prescreened for hepatitis and hiv—and within an hour 40 men and women donate blood. We run this whole blood into two more terribly wounded patients and finally they both begin to stabilize. The Special Forces surgeon returns from the operating room, removes his gown and gloves, and nods approvingly. “I love whole blood,” he says.

Meanwhile, we suspect the sergeant with the broken femur might also have fat embolism syndrome, in which the violence done to the bone pushes the marrow fat into the bloodstream, where it becomes lodged in the brain, lungs, kidneys. We have to stabilize his fracture before evacuating him. In the OR, Sanjay Acharya gives him anesthesia. Moments later, the oxygen content in his blood drops to 38 percent (normal is 95 to 98 percent) and the sergeant turns the color of an eggplant. This is an anesthetist’s worst nightmare—and still Acharya speaks levelly, moves quickly but unhurriedly. We bag the patient hard, adjust his ventilator settings, and slowly his saturations pick up. Orthopedic surgeon Steve Masseours lifts his eyebrows and we all breathe in on the sergeant’s behalf. Finally, his saturations rise to 90 percent and Acharya nods for Steve to begin. I step out of the operating room to look around.

The hospital is carnage; puddles of blood under the stretchers; Dutch, American, Canadian, Australian, and British nurses and doctors all working madly, calling for more blood, more hot blankets, more IVs, another ct scan, more blood, more blood, more blood. From the emergency entrance closest to the airstrip, breathing in the now-evening air, I can see the tents housing the primary-care clinics. Out of them stretches a long line of American blood donors, sleeves rolled up. In one tent, among the phlebotomies and flying paperwork, is a boy—Abdullah, maybe 11 years old—who was badly burned when he failed to notice that the brush he gathered for a fire contained an illumination grenade. When his father arrived at the hospital a week after the accident, Abdullah was still sedated and on a ventilator. Abdullah’s father visited for a few hours and then began the long journey home to the rest of his family in the Panjwei District. Now Abdullah is awake and free of the ventilator, and every night he weeps for his father. Another boy, whose family lives closer to Kandahar, lost a leg after stepping on a land mine; his father remains by his side. Later that night, Abdullah rolls over and calls to the old man, “Please, come talk to me like my father.”

the helicopter crash heralds an upswing in fighting. Every time the weather warms noticeably, the commanding officer tells us to expect more work—by which he seems to mean coalition personnel. There has already been a steadily increasing flow of ana soldiers, anp officers, and men who describe themselves as contractors—South Africans, American ex-military, British ex-military with unit tattoos and the characteristic mustache. Their injuries are suffered far outside the wire and consist of rifle fire, for the most part. No one will say anything explicit. All we are told is that when they are fit to travel, they will be evacuated along with the soldiers.

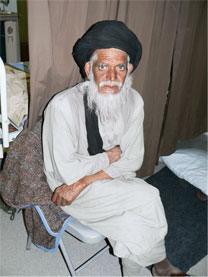

The Afghan soldiers left in our care are preposterously stoic men. They are quite aware of the future an illiterate, legless man faces in that country. And yet they only ever thank the people caring for them. They make it clear that their preference is to leave the hospital as soon as possible, and when the women nurses and medics give them bed baths and change their dressings, their discomfort is evident. Their use of narcotics postoperatively is half of what such patients in North America require. And these are Afghans—men who might know the pleasures of the poppy.

Coalition officers who train ana soldiers believe them to be motivated and brave fighters. “Sometimes a little too brave,” an American major from New Jersey tells me over lunch, “in that if you wait for the artillery and air support to do their work, you don’t always have to run right at the guy shooting at you. But they have fight in them, all right.” A Canadian captain tells me he thinks the media overemphasizes Afghans’ ambivalence about the war. “I keep reading how they’re just doing this for the money, and that they go over to the Taliban all the time. But that’s not what I see out there. The anp is different. They’re mostly village bullies who get into the anp to shake down everyone else. The villagers are pretty leery of them. But the ana soldiers could teach our guys about bravery and cool thinking under fire.”

No one holds the Afghans in greater regard than the American Special Forces soldiers who fight with them. These are strange-looking men: densely bearded and copper-colored from the sun, some dressed in Afghan clothes and carrying AK-47s rather than M-16s; when they speak with American accents I always start. If the mercenaries are reluctant to talk about who they are and what they do, Special Forces make them look absolutely voluble in comparison. They rarely come to our hospital when injured—except after the helicopter crash—but they are adamant that the Afghans they fight with receive the best-quality care. After I help resuscitate a man who took rpg shrapnel in his leg, one Special Forces soldier tells me, “You should have seen him running right at them, rounds falling all around him, like he didn’t even notice.” I don’t know what to say so only nod. The American continues, “Will he keep his leg?” I say that I think he will. There is more emotion in his curt nod of response than I can adequately describe.

These Special Forces soldiers—and in addition to the Americans there are French commandos; British Royal Marine Commandos and Special Air Service soldiers; Canadian jtf-2 special ops soldiers; and New Zealand, Australian, and Danish commandos on base—live in their own compound. (One can imagine the fracas that would result from any mention of Cheese-Eating Surrender Monkeys there.) On Sundays the Special Forces host their own bazaar, and allow regular personnel inside—though a Dutch colonel surgeon discovers the no-photography rule is taken quite seriously when his camera is confiscated. Their inner sanctum seems not much different from any other part of the base—just as dusty, just as prefabricated. But the sense of apartness these men give off is as strong as it is in the dfacs, where they either eat alone or with one another, speaking in low voices and seeming to suffer the proximity of others only with reluctance. They would prefer, one senses, to rid themselves of the need for food as they have the need for every other soft, urban decadence.

The day their helicopter crashed, the less seriously wounded Special Forces searched for any officers or ncos who might know the fates of their platoonmates. I watched one sergeant dissolve into sobs, great heaving gasps, when he learned who the eight dead were. The Special Forces soldiers seem so far into the military they come out the other side, and express a degree of emotion, if only about one another, that no other soldiers in my experience do, emotion that would be much more normal in the civilian hospital I work in, on a Saturday night after a lethal and beer-fueled car crash.

on the evening of March 6, four Canadian infanteers run in through the emergency entrance carrying a fifth. “Gunshot wound,” they yell, as they heave him onto a stretcher. Corporal Kevin Megeney’s uniform is soaked with blood where the bullet has entered his right chest, just below his armpit. His eyes are wide open and his pupils fixed and dilated; there is no pulse. One of the men who brought him in says, “We were just walking by his tent and heard the shot. Sounded like a nine millimeter. No idea what happened.” I open his mouth. His tongue and throat are flaccid and it is easy to see the vocal cords; I pass an endotracheal tube through them and into his trachea, and begin bagging him.

“We need a surgeon here right now!” I holler as I grab a central line kit and begin probing his groin with a needle, trying to find his femoral vein. Lt. Colonel Dennis Filips appears and yells for a thoracotomy kit as he sprays iodine solution over Megeney’s chest. He takes a scalpel and runs it between the soldier’s ribs from his sternum around to his back. Megeney’s lungs bulge out of the incision, inflating and deflating. Liters of clotted blood fall out of his chest in one gelatinous heap. There’s so little blood left in his vessels that no bleeding is evident. Filips saws through the sternum, and extends the incision around to the right chest; this is called a “clamshell” incision and is done only in emergencies. It exposes the contents of the chest completely; surgical residents trying to sound hardened call it “opening the hood.” Filips tries to find a bleeding vessel to repair, while I attempt to get my needle into his femoral veins, which are collapsed flat. One of the nurses finally gets an IV started in his arm; 10 units each of blood and plasma are ordered from the lab. Filips finds the bullet hole in Megeney’s inferior vena cava and aorta—the great vessels leading directly in and out of the heart. There is no cardiac activity at all. The lab tech arrives with armloads of packed red blood cells at the same time I manage to get a line into Megeney’s femoral vein. Filips says, “He’s been pulseless now for 20 minutes. We should stop.” The room freezes as we all realize he is right. Megeney’s entire blood volume has fallen out on the floor.

Megeney has red hair and blue eyes and looks cheerful even in death. We step back as one of the medics begins sewing up the enormous incision stretching around his chest. Someone says, “It wasn’t a pistol. It was a roommate’s rifle.” Another blue-on-blue. The military police begin swarming; everyone in the facility sags as the story comes out. An accident. Ten thousand soldiers who have to carry weapons in order to be served breakfast and it is bound to happen sooner or later. Which is the big picture. But the small picture, tonight, is the death of one 25-year-old reservist from Nova Scotia. When a Canadian soldier dies, Canadian-run communications and Internet access on base are cut off. But as Megeney was dying, he yelled for someone to call his mother. The story is on the Canadian wire service several hours later. Megeney’s mother knows of her loss nearly the moment it occurs. He is the 44th Canadian soldier to die in Afghanistan since 2002.

that same day, three days before my rotation is up, nato launches Operation Achilles. Its objective (aside from having the most ironic name in military history) is, yet again, to clear the Taliban from Helmand Province and seize back control of Kajaki Dam. It is nato‘s largest campaign in Afghanistan thus far, involving 4,500 nato troops and 1,000 Afghan personnel. The initial casualties are horribly lopsided—scores of Taliban killed for each Western soldier. And then the Taliban, for the most part, stops engaging in firefights. The lessons of Iraq extend beyond the nuances of trauma resuscitation. ieds are the Taliban’s new favored strategy: In the weeks to come, ied attacks kill eight Canadians, and previously unseen quantities of explosives become commonplace.

Afghanistan is not Iraq. Not yet. In the north, at least, the government works. The schools are full, and the economy is growing. But it is not clear that order will endure or, in the south, be achieved. The fighting in Kandahar is worse than two years ago. The Taliban’s ranks appear to be growing. Skirmishes have reached the outskirts of Kabul.

The afternoon I leave, as I walk back to the shattered hangar to fly to Camp Mirage, the slopes of Chaghray Kalay glow orange in the setting sun, just as the Coast Mountains do on the shore of British Columbia during late-winter afternoons. In the last few days, the first of the birds have appeared in the tree beside the Green Beans: Little finches and nuthatches chirp merrily as tired nurses and doctors drink their coffee.

The sun is hot now, even when it is low in the sky, presaging the heat that is coming. The sun has dried the mountain passes and the rivers in the Kandahar Valley have swelled. The warmth of the sun puts everything under it into motion—the cheerful little birds, the melting mountain snowpack, and the silent men sleeping in the shadows up in the mountains, waiting for night so they can resume their journey. All of them, and all the people behind me in the hospital—Abdullah, the Dutch, the Danes, the Americans—so far from all of their homes.