The plight of women under the Taliban regime provided the United States with a tidy moral justification for its invasion of Afghanistan—a talking point that Laura Bush took the lead in driving home. “The fight against terrorism is also a fight for the rights and dignity of women,” Bush said after the 2001 invasion, adding that thanks to America, women were “no longer imprisoned in their homes.” Six years later, the burka is more common than before, an “overwhelming majority” of Afghan women suffer domestic violence, according to aid group Womankind, and honor killings are on the rise. Health care is so threadbare that every 28 minutes a mother dies in childbirth—the second highest maternal mortality rate in the world. Girls attend school at half the rate boys do, and in 2006 at least 40 teachers were killed by the Taliban. For two years, Canadian photojournalist Lana Šlezic crisscrossed Afghanistan—from Mazar-e-Sharif in the north to Kandahar in the south—to document these largely hidden realities.

Afghanistan has more than 2 million widows, and these and other desperately poor women often turn to prostitution, despite the risk of being killed by their families if they are discovered. So they remain in the shadows, beneath a double veil of tradition and shame. This woman’s husband is too old to work. She sold her daughter into marriage before the girl was 10, and now she sells herself.

Malalai Kakar became a police officer before the rise of the Taliban. It helped, she says, that her father and brother were also police officers, and her grandfather a tribal elder. When the Taliban rose to power, she fled to Pakistan. When she returned to work after they were ousted, she received death threats. To “protect her honor” and her family, the mother of six patrolled with her brother and wore a burka in the field. But she goes uncovered now, so as to “tell women about their rights.”

Self-immolation has long been the preferred method of suicide in Afghanistan, but “the trend is upward,” says Ancil Adrian-Paul of the women’s nonprofit Medica Mondiale. Girls as young as nine set themselves ablaze, typically with cooking oil. In Herat Province, where last year 90 women lit themselves on fire, Zahra spent 93 days in the burn unit. Her husband beat her regularly, told her she was worthless and should just light a match. So she did. She is, by some accounts, lucky: More than 70 percent of victims of self-immolation do not survive.

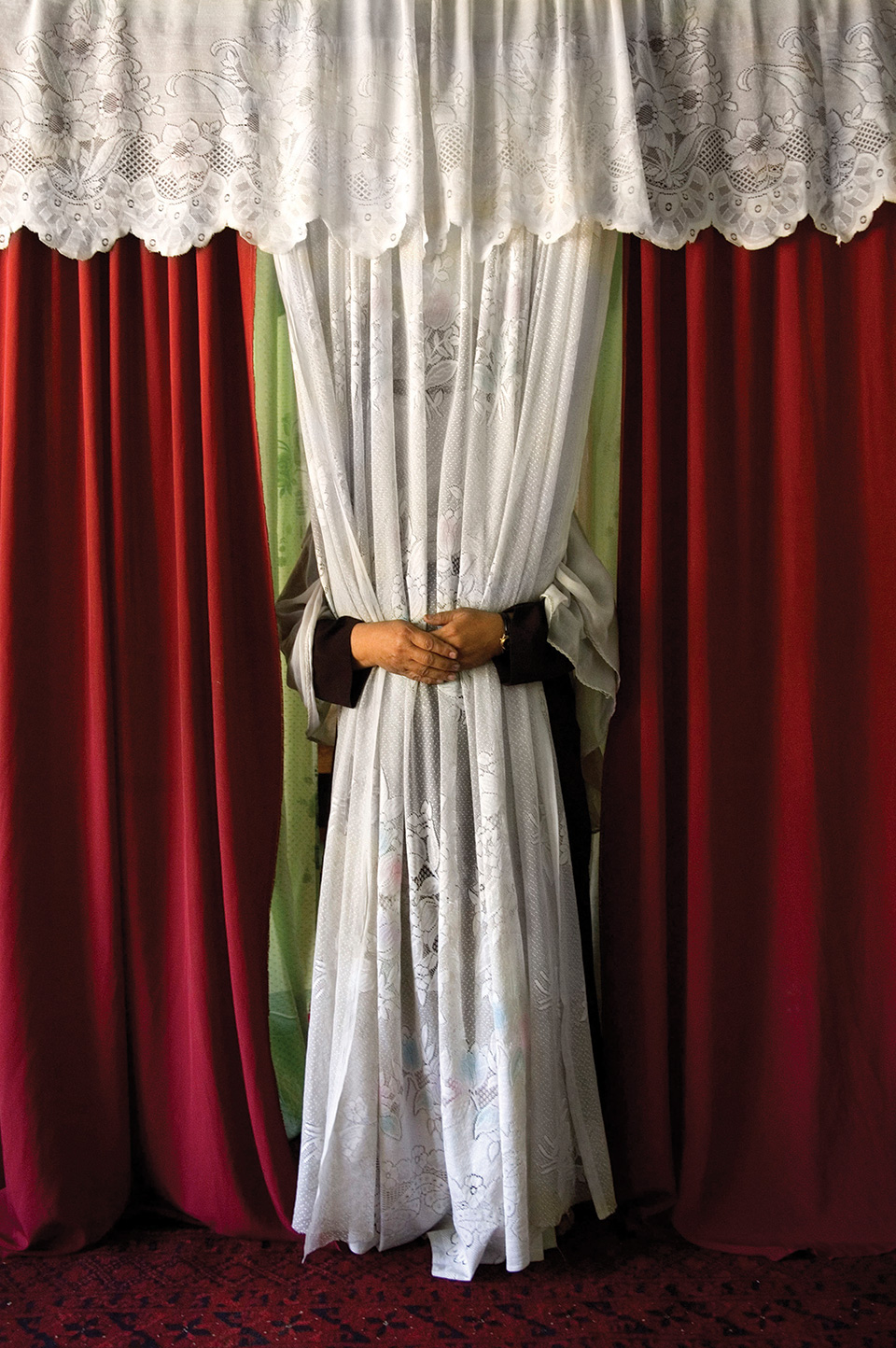

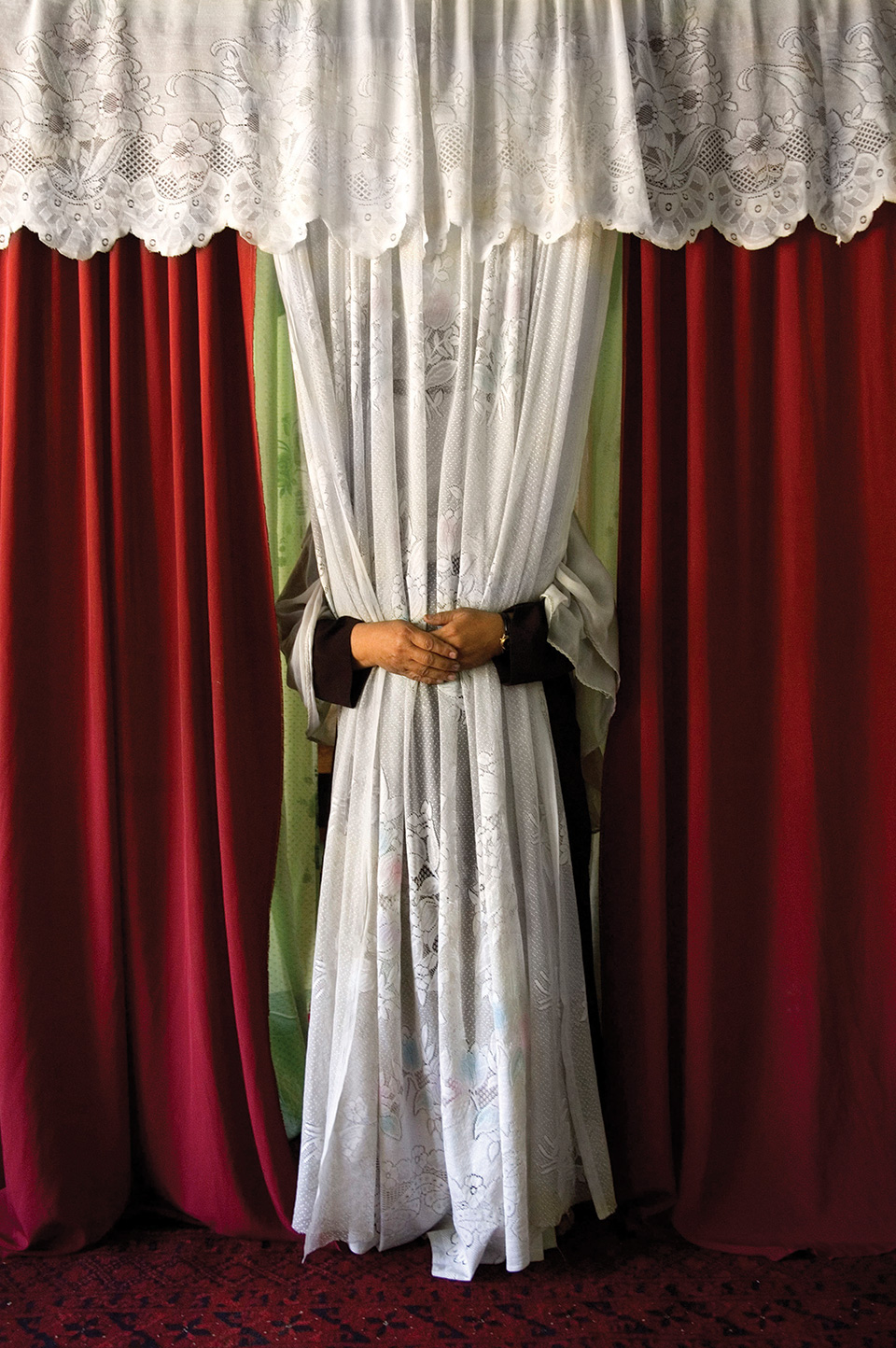

Inside a Kabul home, a heavy curtain is all that separates a prostitute’s work from her family life. Her 15-year-old daughter also sells herself, but not in the house. Too many men going in and out would alert the neighbors, and that could prove fatal.

On the day of a young boy’s circumcision, these girls don lipstick and their very best dresses. If the odds hold, only a couple of them will receive an education. Just one in five Afghan schools are designated as girls’ schools; coed schools are banned. A third of Afghanistan’s school districts have no girls’ schools at all, and the schools that do exist are under constant threat of attack.

The streets of Afghanistan are pocked with divots and gaping potholes, and there is hardly any pavement to speak of. Still, heels are the norm, and beneath their burkas many women wear bright, beautiful dresses.

The waters of Band-i-Amir Lake are thought to cure many ailments, including infertility. If a woman has not conceived soon after marriage, her husband’s family will often travel for days-by car, donkey, camel, or foot-to bring her here. Most Afghans don’t know how to swim, so the woman is tethered around the waist as she enters the lake. The husband follows behind and, as is the custom, pushes her into the frigid water three times.

October 9, 2004, saw the first free, democratic presidential election in Afghanistan. In the months prior, the Taliban peppered villages and cities with “night letters” warning women not to vote. In June 2004 a bomb exploded on a bus full of female election workers in Jalalabad, killing three. Still, these four women at a Kabul polling station-and 40 percent of women nationwide-asserted their new right. But, as a Womankind report summarized, “paper rights have not equaled rights in practice.”

Twenty-four-year-old Shaima Rezayee hosted a popular music show on Tolo TV. She was strong, independent, unmarried, and she refused to wear the burka. In 2005 her sister found her dead in her Kabul apartment, shot in the head. Rezayee’s brothers were charged with her murder-a rarity, as few are ever prosecuted for honor killings.

Sold for $60 at the age of four, Gulsuma was promised to a six-year-old boy who, in the end, was the only member of his family who didn’t abuse her. For seven years Gulsuma was beaten with rocks, slabs of wood, anything and everything within reach. Then one day her father-in-law accused her of stealing his wristwatch and threatened to kill her. That night she fled. Today, she lives in a Kabul orphanage, where a few cherished belongings are kept in a little tin trunk at the foot of her bed.