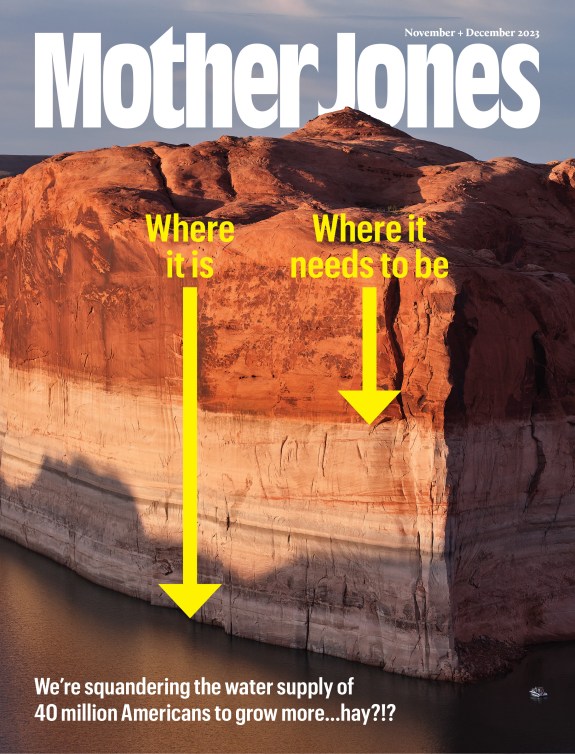

ever wonder why cashmere, not so long ago a luxury item off-limits to most, suddenly appeared on the shelves at J. Crew and H&M and Wal-Mart, and why seemingly every American woman now owns at least one pashmina shawl? The answer is an object lesson in the ripple effects of globalization. In 1981, a Chinese official established a cashmere-sweater factory in Inner Mongolia. Goats were bred to supply it. The factory begat more factories, the goats begat a lot more goats, until 26 million were devouring Inner Mongolia’s fragile plains. The price of cashmere plummeted, Americans bought more of it—10.5 million Chinese-made sweaters in 2005, a fifteenfold increase in a decade—more and more goats ate more and more grass, until China was losing a Rhode Island-sized parcel of land to desert each year.

Or take Ikea’s Jokkmokk dining set: made in China, of course, by people working for pennies. On the way to becoming the world’s largest producer of furniture, China learned a hard lesson about deforestation. In 1998 a flood on erosion-prone land destroyed 5 million homes. “As a result,” writes Jacques Leslie in our cover story, “China declared a logging ban on what little remained of its old-growth forests. Most environmentalists applauded the ban until they grasped its corollary: Chinese companies began harvesting other countries’ trees on an even grander scale.” Today, Thailand and the Philippines have been stripped of most of their forests; those of Indonesia, Burma, and even Siberia will be gone in less than 20 years. Enter Ikea: Most of its Chinese-manufactured “Swedish” furniture is made from Russian pine, often logged illegally, and sometimes culled in the wake of arson fires set to exploit the salvage market. In 2003, North Dakota-sized fires in Siberia drove ozone levels above epa limits in Seattle, 5,000 miles away. And fewer trees not only means less carbon is sequestered, but (thanks in part to fires) deforestation accounts for one-fifth of global greenhouse gas emissions, more than all the world’s trucks and cars and planes combined.

Consider, too, that most of the power feeding all those furniture and cashmere factories comes from coal, pushing its greenhouse emissions above even those of the profligate United States; that mercury and sulfur dioxide from those coal plants travel around the globe; that the dust blowing off of China’s new deserts now threatens to violate air-quality standards in California. We exported our pollution along with our jobs, but nowhere on the planet is distant enough to insulate us from the consequences. It’s the old butterfly effect: Factories in China will lead to asthma and hurricanes in America. Suddenly, those $20 sweaters and $120 dining sets don’t look so cheap.

China knows it has a problem—officials have even admitted that the costs associated with pollution entirely erase its celebrated economic growth rate—but they’ve had a hard time enforcing nascent regulations in the face of corruption and global demand. But have we admitted our part of the problem? China’s environmental destruction has thus far been driven by our appetites. The average American is 10 times wealthier than the average Chinese, and were they to catch up to our levels of conspicuous consumption it would require the resources of several Earths. But they seem determined to try, and as it stands we have no moral authority to lecture them on sustainability. As the nation with the most money, the most R&D capacity, not to mention the most to lose, we should lead by example.

No such luck. As we went to press, congressional Democrats appeared ready to cave to utilities, Detroit, and the gop and jettison critical provisions of an energy bill years in the making—fuel-efficiency standards, renewable-energy mandates and subsidies—without so much as a whimper. True, “trade” is back on the agenda among presidential candidates. But the talk is of the loss of American jobs, and the threats that Chinese toys pose to American children. Little is made of the fact that environmental damage, like the marketplace, knows no borders and that unsustainable profits are not profits at all. And what politician tells Americans to spend more and buy less?

Fifteen years ago, as Bill Clinton offered a sunny vision of a shared hemispheric boom, nafta opponents warned that the treaty could provide no winners except corporate America. They’ve been proven right, as even Hillary now admits. Besides hollowing out vast stretches of the American manufacturing sector, the deal decimated Mexico’s most vulnerable: craftspeople, subsistence farmers, small merchants. They’ve come north, giving our politicians another issue to both exploit and ignore. The lesson is that in a global marketplace—and at this point there can be no other—product will move, but so will people and so will pollution. It’s time to stop pretending we can have everyday low prices and not pay the true cost.