From Jeffrey Klein, former Mother Jones Editor-in-chief:

Senator Howard M. Metzenbaum called me into his office late one morning in January of 1981. Several months earlier I’d written a cover story for Mother Jones predicting what the first four years of a Reagan administration would look like. As luck would have it, I’d gotten a jump on the national press corps, who initially thought this aging B actor didn’t have a prayer of being elected president. But because Mother Jones was based in San Francisco, we knew that it was the country that needed to pray.

A sidebar in the Mother Jones‘ story had caused the sudden resignation during the Republican convention of Reagan’s foreign policy advisor, Richard Allen. We’d exposed that Allen, while serving on Nixon’s payroll, had simultaneously worked for Richard Vesco, then the world’s biggest swindler.

After being elected in a landslide, Reagan resurrected Allen and announced he would appoint him National Security Adviser.

“I can’t help you with that,” Senator Metzenbaum said gruffly. “It’s not a confirmation post.”

Knowing that his time was limited, I dropped my Richard Allen files to the floor and picked up my stack on William Casey, Allen’s buddy, whom Reagan had chosen to be the new CIA Director, a post that did require Senate confirmation. “Casey is an even bigger swindler,” I said.

Soon Senator Metzenbaum told his secretary to cancel the rest of his morning appointments. (I don’t know if he had any—Senators love to convey importance to those in their presence.) “I’m going to take this young man to lunch.”

We went to the Senate dining room via the underground trolley. Many Senators were coming and going; Metzenbaum went out of his way to offer courtesies to each colleague, including Sens. Thurmond and Helms.

After these particular greetings, I tried to get Metzenbaum to say something revelatory, or at least catty. All he offered was: “We’re in the same club.”

At lunch in the Senate Dining Room, Metzenbaum’s power was immediately apparent. One Republican Senator introduced young John Lehman, whom Reagan had nominated to become Secretary of the Navy. Another Republican called “Howard” as he came up from behind and whispered something into Metzenbaum’s ear. The Republicans had gained a majority in the Senate, but the filibuster torch had been passed from Thurmond and Helms to Howard Metzenbaum. Every one of his colleagues knew that Metzenbaum’s convictions were so strong, he’d have no trouble holding this torch aloft night after night.

Metzenbaum focused our conversation on the tax shelter schemes Casey had peddled earlier in his career. A successful businessman himself, Metzenbaum wanted to understand Casey’s m.o. After he took shrewd measure, the Senator abruptly said: “I can’t help you with this one either. We don’t have enough votes.”

Next the Senator wanted to hear more about Reagan’s attitude towards “working people.” He didn’t like what heard.

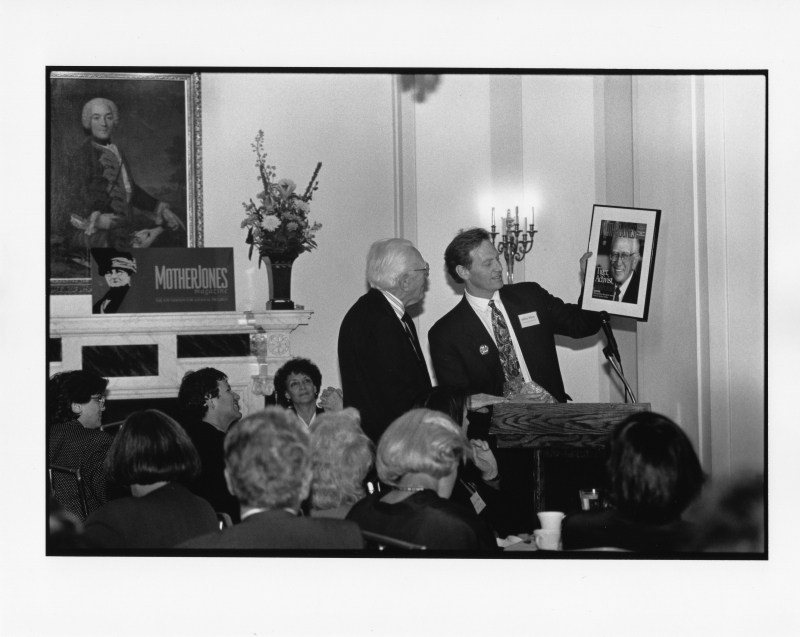

The picture above, taken 14 years later, shows Mother Jones giving Senator Metzenbaum a lifetime achievement award. At this luncheon, I privately asked him, “What piece of your legislation are you proudest of?” It was the only time in my conversations with him that he was at a loss for words. Senator Metzenbaum’s great gift to the country, as his colleagues all recognized, was not to produce legislation— but to stop many crooked parts of many crooked bills from becoming law.—Jeffrey Klein, former Mother Jones Editor-in-chief