In April 1968 I was a Columbia University freshman, restless, raw and clinging to fond illusions. So when I saw three men with blackjacks pummel a Spanish-language instructor on the sidewalk and dump his semiconscious body over a hedge in front of Low Library at the center of the campus late one night, my first instinct was to run to the police for help.

It was sometime after midnight on the morning of Tuesday, April 30, and uniformed policemen weren’t hard to find. Hundreds of them were taking positions around the campus preparing to evict student demonstrators who had been occupying the university president’s office and four other buildings for a week to protest the Vietnam War and other sundry matters. One unit of the leather-jacketed Tactical Police Force, New York City’s toughest and tallest officers, was lining up in a neat double row outside one of the entrances to Low. I dashed up to the officer in charge, a silver-haired sergeant who stood a good six inches taller than me. “You’ve got to send some men over there!” I pleaded, pointing to the nearby hedge. “Some thugs are beating the crap out of my Spanish teacher!”

He didn’t move a muscle, didn’t say a word, didn’t even glance down at me, but just the hint of a smile grazed his lips. He must have thought I was either a particularly sardonic campus comic or just plain stupid. Because everyone else but me seemed to know very well what I was only beginning to realize——those three thugs, and dozens of others roaming the campus that night, were plainclothes officers sent to soften up the area by eliminating protesters and bystanders from the scene to make it easier for the uniformed men to carry out their mission with a minimum of witnesses and resistance.

Within hours hundreds of officers evicted the protesters and pacified the campus in their own special way, using clubs, flashlights, and handcuffs to administer beatings like furious parents lashing out at recalcitrant children. About 150 people went to the hospital to be treated for bloody heads and broken arms, and some 700 were arrested. I watched much of it in horror and fascination until someone whacked me on the back of the head with a nightstick and two plainclothesmen grabbed me by the arms and threw me down a slope into a wrought-iron fence bordering Amsterdam Avenue. I staggered back to my dorm room with a sore head and a deep sense of anger at the administrators who’d invited the police on campus to restore order by beating my classmates and me.

This April marks the 40th anniversary of that particular teachable moment. It will no doubt provide an opportunity for some aging baby boomers to renew the old culture wars with their dying elders and each other and brag about their exploits, real and imagined. I plan on doing neither. I was a wide-eyed witness to events I barely understood and only marginally participated in, and I’m still embarrassed and amazed at the arrogance and ineptitude on all sides—students, teachers, administrators, cops—in that long-ago struggle. There were more than 100 student university protests in the United States that spring, but none got more publicity than Columbia’s. For the university, it was a terrible rupture that provoked years of soul-searching and institutional reform. For me personally the damage was slight—a nagging headache for a day and a permanently disrupted spring semester—but the lesson was unforgettable.

What I first recall about my arrival at Columbia the previous fall was the decrepitude of the dorms. Livingston Hall, where I was assigned, was dark, dingy, and overcrowded. Most rooms were designed for single occupancy but had been fitted with bunk beds. They were so small students stacked the ancient wooden dressers atop each other and bookshelves atop desks to create enough space to get to the bed. There was no room for even the smallest refrigerator; in winter we would balance cartoons of milk and orange juice on the outside windowsill to keep them cool.

Everyone’s experience was different, of course, but for me and the few friends I made the chill extended to the classrooms. Our teachers could be brilliant, but most had little interest in freshmen, and no one encouraged us to approach him outside of the classroom. I recall meeting with my academic adviser once in four years. Barnard, the women’s college, was a distant fortress across Broadway, off-limits and out of sight. On most weekends I wandered the unruly, decaying urban canyons of Manhattan on foot and alone. It was my true education. Meanwhile, the draft was hanging over our head, forcing many young men to stay in school despite their abiding discontent. Opposition to the Vietnam War was hardening; that October, protesters staged the first mass rally in Washington.

One campus group that seemed interested in us was the Students for a Democratic Society. Members organized an orientation session for freshmen and arranged one-on-one meetings. I recall my roommate John and I going for coffee at the College Inn on Broadway with Ted Gold, one of SDS’s leaders. We weren’t exactly prime recruiting material for a radical student group. John, who joined the crew team and pledged a fraternity, was a conservative Democrat from Worcester, Massachusetts, who aspired to become a lawyer. I was an inchoate liberal with a soft spot for Robert F. Kennedy. I admired Columbia, felt lucky to have been accepted at such a prestigious Ivy League school. Still, for me Gold was logical, insistent, and amiable. Even John had to admit he was interesting.

There were various skirmishes between SDS and the administration during the school year. The group focused on two campus issues: Columbia’s plan to build a new gym on city land in nearby Morningside Park, which bordered on Harlem, and its membership in the Institute for Defense Analyses, a federally funded national security research and development center. The two issues were stand-ins for broader questions: The gym was about racial justice, the IDA Vietnam. After an indoor demonstration in late March led to the proposed suspension of a half-dozen SDS leaders, the group added another demand: amnesty for the protesters.

Demonstrators on Tuesday afternoon, April 23, sought to march on Low Library but were blocked by student opponents and campus police. Some protesters tramped over to Morningside Park, where they confronted police at the gym construction site, then wandered back to campus. Running out of steam and options, they turned their focus to Hamilton Hall, the main undergraduate classroom building. Acting college dean Henry Coleman refused to vacate his office, so they sat down outside his door, blocking his freedom of movement. The standoff continued into the night until early the next morning when black students among the protesters seized control of Hamilton Hall and ordered out the whites. The evictees proceeded to smash their way into Low Library and seize the office of university president Grayson Kirk. Over the next two days, three more classroom buildings were occupied. The siege had begun.

Most of us were stunned to find our classroom buildings suddenly off-limits. Many of us simply wanted to be left alone to continue our studies. But large minorities on both sides took a stand. It was an Ivy League version of West Side Story. On one side were the jocks—athletes and nerds, many of whom dressed like they came from a previous era. They were furious that a handful of leftist agitators had succeeded in paralyzing their beloved institution while a weak-broth collection of teachers and administrators stood by passively. On the other side were the pukes, named for their scruffy hair and attire. Some were true radicals, but most were fed up and suspicious of a dysfunctional university that failed to practice the liberal values it preached. My roommate John was a jock—he wore a white shirt and blue blazer to a gathering outside Hamilton Hall where the newly formed Students for a Free Campus sought to seal off the building and isolate the demonstrators inside. I was an aspiring puke—I had the unkempt long hair, flannel shirt, and denims for the role, but lacked the conviction. John and I found ourselves on opposite sides of the line that morning, although neither wanted to confront the other. Then, to our mutual surprise, our favorite instructor, a sociology professor named Martin Wenglinksy, joined a small cordon of concerned teachers who positioned themselves between us. It was the first time I’d ever seen him outside of class.

The radicals were an arrogant crew. A few weeks earlier Mark Rudd, the newly elected SDS leader, had confronted university vice president David Truman, one of the more respected figures on campus. Truman had tried to get by a group of protesters to enter a classroom building, saying, “I have an appointment.” Rudd’s retort: “Adolf Eichmann had appointments too.”

The siege was a windfall for Rudd, and he used it as a publicity and recruiting tool. His stated goal was to bring the university to its knees and he made no effort to hide his agenda. His sole saving grace, in my view then, was that he freely applied his withering disdain. A few days into the crisis, folk singer Phil Ochs arrived at Ferris Booth Hall, the student union, to cheer us on. He sang a half-dozen protest songs to great applause. Then someone announced that a hat would be passed to pay for Phil’s cab fare and thank him for the free performance. Rudd grabbed the microphone. Don’t bother giving your money to Phil Ochs because he doesn’t need it, Rudd told us. If you’ve got any spare change, contribute it to the committee supplying food to the strikers occupying the buildings. Ochs left empty-handed.

Dean Coleman was allowed to leave his office after 26 hours, while the siege dragged on for a week. An ad hoc faculty group futilely sought to negotiate a compromise between administrators and the protesting students. The campus became a magnet for anarchists, Maoists, bohemians, Trotskyites, and angry young blacks from Harlem. Celebrity radicals like H. Rap Brown, Stokely Carmichael, and Tom Hayden made guest appearances. (Hayden stayed to join the “commune” occupying the mathematics building.) Nearly 300 journalists, TV cameramen and reporters, photographers set up shop on campus to watch the spectacle unfold. One inspired couple in Fayerweather Hall got married late on Sunday night; the Episcopal priest who presided pronounced them “children of the new age.”

I gravitated to Avery, the loosest and least radical of the five occupied zones, although I never spent the night away from my dorm room for fear of the police bust that everyone knew was coming.

The administration, led by Kirk and Truman, seemed aloof and clueless. The deeply divided faculty shuttled from one side to the other with lists of conditions and demands, as if they were mediating a labor dispute instead of playing the role of hapless liberals in a moment of political theater. The faculty overwhelmingly opposed amnesty but almost as strongly feared police action. Students on both sides seethed with discontent. Each side accused the other of fascism.

Finally, after seven nights of chaos and ineptitude, Kirk and Truman called in the cops. They first obtained assurances that the campus would not be cleared wholesale and that the demonstrators would have sufficient warning to leave peacefully. They planned for the bust to occur at 4 a.m., when the campus would presumably be nearly deserted. It didn’t happen that way. The 88 black students occupying Hamilton Hall were escorted out through a tunnel to Amsterdam Avenue with dignity and calm to awaiting paddy wagons. But the administration and the police had sorely underestimated the number of white demonstrators in the other buildings, plus the 1,500 people—many of them undergraduates—milling around campus. The police were outnumbered and caught by surprise. They changed their tactics without warning or consultation, turning their fury first on the bystanders to get us out of the way, then hauling the protesters from the buildings into paddy wagons.

Kirk’s office was left a shambles. His personal photos and private possessions were smashed, his files looted, slogans and obscenities daubed on the walls. New York Times reporter A.M. Rosenthal, who accompanied the president, watched as Kirk wandered the suite in a trance. “How could civilized human beings act this way?” he asked.

David Truman, devastated by the violence, walked home to his Riverside Drive apartment and wept.

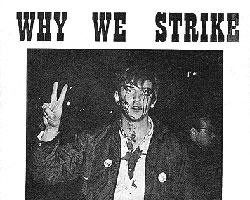

The next day I pulled myself out of bed and signed up for strike duty, my anger and alienation now focused on the university administration. The plainclothes cops who had beaten the Spanish instructor and many others still stalked the campus in small groups. They wore colored pins in their jackets to identify themselves to each other. They seemed as arrogant and smug as Rudd and his SDS comrades. I recall one of the cops eyeing me with a smirk, as if to say, “I know your face, and I’ll be looking for you next time.” I felt intimidated—and bitter. I was hardly alone. The police tactics shocked and radicalized many students, creating massive support for the strike. SDS members refused to report for disciplinary hearings. The pressure was on the administration, not the students.

Columbia became the new popular front in the Age of Aquarius. Allen Ginsburg, Herbert Marcuse, and the Grateful Dead arrived to admire and entertain us. With formal classes suspended, students signed up for liberation courses like “Sexual Intercourse as a Political and Human Reality,” “Motorcycle Mechanics,” “Moderately Liberated Talmud,” and “Imperialism and National Liberation Movements.”

A second round of confrontation was inevitable. On May 21, SDS led another occupation of Hamilton Hall. Vandals lit fires in some of the buildings, and by early the next morning we had built makeshift barricades on both ends of Campus Walk bordering both the Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue. I stood against the Broadway barricade as the police on the other side described with great relish what they planned to do to us when they got the order to move in. “It’s my campus!” I yelled back at them. It was a dialogue of the deaf.

Just before 5 a.m. the cops broke through, nightsticks flailing. This time the violence was mutual—students threw rocks, bottles, and paving stones. My friends and I retreated to the safety of our dorm. But not everyone made it. The police pursued some students as high as fourth-floor stairwells. There were 171 arrests. Nearly 17 police and 51 protesters were injured. School was closed until fall.

Grayson Kirk retired in August. The university dropped plans to build the gym and quit the IDA. Columbia’s $200 million fundraising campaign suffered a major setback. A special commission led by Harvard law professor Archibald Cox concluded that “the seizure of the buildings was not simply the work of a few radicals” but had “involved a significant portion of the student body who had become disenchanted with the operation of their university.”

David Truman, the talented vice president and provost whom everyone had tagged as the next president, resigned the following January to become president of Mount Holyoke College, a much smaller institution. I still recall the press release announcing his departure: It said he had always been extremely interested in higher education in the Connecticut River Valley.

The leaders of SDS followed the logic of their ideology and descended into the violence of the Weather Underground. Nearly two years after the Columbia strike, Ted Gold and two others were killed in an explosion in a Greenwich Village town house. They were building a bomb that they planned to use at a military dance at Fort Dix. The line between idealism and terrorism had been obliterated. Mark Rudd spent seven years in hiding and emerged still committed to radical change but renouncing violence. I suspect I’d like him a lot better now.

The men who took over running Columbia were less rigid and more creative than Kirk and Truman. They scrapped all of the bunk beds in Livingston and reconverted the narrow rooms to singles, knocked out the walls between two small rooms in the middle of each floor and turned them into lounges with couches, arm chairs, and color television. Cable TV became the opiate of the undergraduate masses—we learned to care more about the fate of the New York Knicks than the Cuban masses. The rules strictly governing when women were allowed upstairs were at first eased, then abolished. After a year of living in an apartment, I returned to Livingston Hall as a dorm counselor—a collaborator in the system I richly despised. The administration had bought us off with a lounge and a television and the prospect of sex. Too bad for them they hadn’t thought of it sooner.

After graduation I eventually became a journalist, and a series of lucky breaks got me in 1979 to the Washington Post, still basking in post-Watergate glory. Journalism was a good fit for my ambivalence and my slowly melting alienation—I could be an insider and an outsider at the same time, learn the inner workings of institutions and the people who powered them yet at the same time be a critic. Surely the seeds of that stance were planted at Columbia, where I had embraced neither the institution nor the radicals who sought to destroy it.

In the 1980s I became a foreign correspondent and did tours in Southern Africa, Jerusalem, and London. Those are the places where I rediscovered deeper lessons from Columbia. Kirk and Truman had been reluctant to use state power—once they called in the police, they accomplished their immediate goal but alienated their allies, radicalized the uncommitted, and destroyed themselves in the bargain. Over and over again I saw the same process take place in the countries I covered. Even in apartheid South Africa, the rulers of the white-minority regime were slow to use police violence to regain control of the black townships, realizing they couldn’t control its consequences. They were much more comfortable with so-called surgical strikes like assassinations and “disappearances” than with large-scale repression. The same was true in Israel during the first Palestinian uprising, where the proud Israeli Defense Forces rebelled against its despised role as riot police in the occupied territories and helped drive its civilian leaders to the bargaining table with its vanquished Palestinian foe. And in Northern Ireland leaders of both the British forces and the Irish Republican Army found that violence became a double-edged weapon they could no longer wield without permanently damaging themselves.

“Violence is the last refuge of the incompetent,” wrote Isaac Asimov. That’s the real lesson I learned in front of Low Library that April night 40 years ago.