Is the worst over? Are we on the road to recovery? Will the next president take office against a backdrop of economic improvement, as Bill Clinton did in 1993? Or has something deeper and more intractable gone wrong?

Early this year, the optimists, including Citigroup chairman Bob Rubin and Treasury secretary Hank Paulson, argued that the slowdown was short-term and that a “stimulus” package should be “targeted and temporary.” This with rare haste the Democratic Congress enacted. As a result, most taxpayers got one-time $600 checks in May, prefigured by bubbly messages touting “Good News!” if you filed your taxes electronically.

The rebate isn’t the only little Dutch boy thrown headlong at the dike this election year. Government spending, especially for defense, will be up: Military spending as a share of gdp is expected to grow by $75 billion in fiscal 2008, enough to neutralize a 0.3 percent decline in gdp. Dick Cheney was secretary of defense for Bush 41; just before the 1992 election he engineered a big run-up in outlays, as the military restocked following the first Gulf War. (It was exposed in the first Clinton “Economic Report.”) Is the Pentagon up to that trick again? I’d be astonished if it were not.

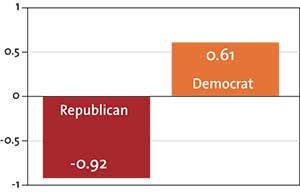

Under intense pressure from panicky bankers, Ben Bernanke cut interest rates relentlessly from August 2007 through the spring of 2008. I don’t accuse Bernanke of playing politics. But it’s worth noting that this is what usually happens. In presidential election years when Republicans are in office, the Fed regularly and predictably pursues a more expansionary policy than when Democrats rule—after controlling for differences in the rates of inflation and unemployment. (I made these calculations myself; see the chart.) Maybe they just can’t help themselves.

But much of the ordinary effect of interest cuts on new lending—like a rebound in construction and automobile sales—didn’t happen this time. That’s because the fall in home prices (and therefore the value of collateral) overwhelmed the benefit of cheaper money to the banks. And the banks barely cut mortgage rates, so consumers saw no benefits at all. Lower interest rates did cut the value of the dollar, however, and that promotes exports and foreign investment. (These days New York Times real estate listings come with a currency converter.) It also boosts the stock market, since multinational firms can report their (unchanged) foreign income as higher dollar earnings.

Possibly all this stimulus will ward off the two-quarter decline that has historically defined a recession. Don’t be surprised: Republicans haven’t had an election-year slump since 1960. On the other hand, the National Bureau of Economic Research, which has the official call, may describe the early spring as a recession anyway. Republicans will welcome that, too, so long as they can plausibly call the summer a “recovery.” Even if they can’t stop a recession, they may be able to make it short and shallow enough, this year, to put John McCain in the White House. But all this brings up an important question—what of next year?

You get what you pay for

How Fed’s election-year rates varied from nonelection years when the incumbent was:

1984-2004. Source: Galbraith et al report, page 20.

No matter how effective the stimulus, two enormous clouds remain for whoever becomes president: the housing slump and the banking crisis. Both are far from being finished yet.

The problem with a housing slump is inventory. Unlike factories and Internet startups, shuttered houses don’t go away. No one declares them obsolete. They aren’t boxed up and sent to China. They remain, a drag on the market, decaying and pulling down property values for years. Here in Texas, housing values slumped with the S&L crisis and the oil bust of 1985 and did not recover until around 1993. That slump clobbered the oil patch but was barely felt anywhere else. This slump is the reverse—it’s driving down housing prices just about everywhere except Texas, where the scars of the last bubble helped keep the recent one under control.

Nationally, the subprime debacle is blowing away the homeownership gains of the last few years. Those abusive mortgages were deliberately targeted at vulnerable, even desperate, people who could be steered into financial death traps. Lenders didn’t care, because with the help of fraudulent appraisals, the loans could be off-loaded quickly in packages bought by greedy or gullible investors, including your pension fund. Poor people got hit on the front end; 1.5 million homes entered foreclosure last year. Middle-class people got it on the return volley.

And middle-class homeowners are now getting hit a second way: in the declining value of their homes. You don’t have to be holding a subprime to find yourself underwater. That means that home-equity loans will dry up. (As of April, California homeowners in default were already a median of eight months behind on those loans.) Many people will be tempted to walk on their houses and mail the keys to the bank. Incidents of the foreclosed expressing themselves to their lenders by yanking the plumbing and the wires on the way out the door are on the rise, as is arson by desperate homeowners, according to the Los Angeles Times. Will students, small businesses, and other borrowers still be able to get credit when this is over? God only knows.

The mechanisms of mortgage finance and home-equity drawdown haven’t simply been damaged. That well has been poisoned. Having largely outsourced mortgage originations to companies like Countrywide who didn’t care whether the borrowers had good credit, the banking system cannot easily go back to its old method of making loans to creditworthy people and contenting itself with the interest paid back over many years. And who would trust them, anyway, if that’s what they claimed they wanted to do?

Then there’s another problem: The banks no longer trust each other. Last August, as mortgage-backed securities unraveled, finances froze up worldwide. Why? Because banks knew how much undisclosed junk they had on their own books. Who could say what the next fellow had? Overnight lending between banks—the process that ensures that every bank has funds when it needs them—fell apart. This is a very big deal. If banks will not lend money to each other, why (except for the blessings of federal insurance) should anyone else leave their money to them? Economists like me wait entire careers to study events such as these—which should provide no comfort to anyone else.

Since August, America’s big banks have been wards of the Fed, and those in Europe equally so of the Bank of England and the European Central Bank. The system survives because central banks keep the lending windows open, and the result is that—except for one instance in Britain—the public has not pulled out of the banks. Let’s be clear. The private financial markets did actually fail. It’s only the fact that the public trusts government that keeps the system from dissolving in panic. But even if the Fed and its counterparts can hold the line, the problem of mistrust among the big bankers won’t go away soon. And that means we’re at the end of the age of credit expansions, for now.

As for next year, good luck. No matter who becomes president, there probably won’t be another tax cut. Instead, cries for “fiscal responsibility” will be heard. States and localities, hit in 2008 on their property taxes, will cut their spending. Consumers, hit hard on their home equity, will cut back on new borrowing (which they probably couldn’t get anyway) and pinch pennies however they can. Businesses won’t even think about new investments.

In this situation, more cuts to interest rates—the only applicable tool the Fed has—don’t work well. And they weaken the dollar, which raises inflation. What is gained by cheaper money will be lost in higher gas and food prices. But if the Fed reverses field and defends the dollar, exports will slump and the housing crisis will get worse. There’s no easy way out.

Thus far the dollar has fallen, but it hasn’t collapsed. Will it? There are two big threats. The first is the financial crisis itself, which is a problem of trust not only in the ordinary borrower, and not only in the banks, but in the American dollar. Why is the rest of the world nervous? Because the fundamental trust that they have always had—that the United States was a safe place to put your money—has come into question.

The second threat, not often mentioned, is our reckless foreign policy, including the invasion of Iraq, bellicosity toward Iran, and the ongoing subtext of hostility toward China. Since the Middle East has the oil and China holds our debts, all this is spitting in the soup, big time. It may not by itself wreck the financial system. But it doesn’t exactly build up the reserve of good will that we may need when the financial going gets tough.

For half a century much of the world believed that we provided security under which they too could prosper; many no longer think so. Today, our country, like our banks, has a problem of global trust. Unlike the banks, we have no higher power to keep things going if we screw up.