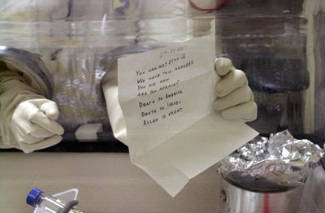

Shortly after the 2001 anthrax attacks, U.S. bioweapons researcher Bruce Ivins emailed some poems he’d written to a friend, including this one: “I’m a little dream-self, short and stout. I’m the other half of Bruce—when he lets me out. When I get all steamed up, I don’t pout. I push Bruce aside, then I’m free to run about.” The previous year, he’d confided to a friend that he was feeling deeply depressed and acknowledged that his psychiatrist believed he might be suffering from “Paranoid Personality Disorder.” Combined with everything else we’ve learned about Ivins in the last week—his late nights at the Fort Detrick lab; his professional disappointments; his obsession with sorority girls; his threats against his counselor; his long history of sociopathic and psychotic behavior; his custody of an anthrax vial considered to be the “parent flask” of the material used in the attacks; and even his possession of what the FBI has declared to be a suspicious book, The Plague by Albert Camus (couldn’t he just have been well-read?)—Ivins seems to fit the profile of someone capable, personally and professionally, of sending the anthrax letters.

The Justice Department and the FBI appear to be satisfied that he did, declaring at a press conference yesterday that Ivins was “the only person responsible” for the attacks. Even after it described its evidence against him, while ordering the simultaneous public release of 14 affidavits and search warrants, the Justice Department’s case remained largely circumstantial—something US Attorney for the District of Columbia Jeffrey Taylor freely acknowledged. “Circumstantial evidence?” Sure, some of it is,” he told reporters. “But it is compelling evidence.”

Not so, says Ivins’ lawyer, Paul Kemp. Far more people, numbering perhaps in the hundreds, had access to the so-called parent flask (the “murder weapon,” according to Taylor) than the FBI has admitted, he argues. “The idea that anyone could say they could convict someone with what they have is stunning,” Kemp told NPR. “They have nothing. There was not a single piece of evidence produced from all those search warrants and all those affidavits. He was a weird, bookish, nerdy kind of man. But he didn’t do it. He was an open, caring, honest man with a great sense of humor who was beloved by his friends and family.”

Hmm. Maybe, but there’s little doubt that Ivins’ suffered severe psychological problems. And given his history, it inspires very little confidence that he continued to have access to the Fort Detrick laboratory until November 1, 2007—six years after the anthrax attacks. That fact forms part of the basis of a lawsuit filed in 2003 by Maureen Stevens, the widow of Robert Stevens, who died after receiving an anthrax-laden letter at his office at the National Enquirer. She’s suing the federal government for $50 million dollars, charging that it is responsible for the death of her husband. Ivins “was not just a little weird,” she told reporters today. “He was certifiable, and he had been for years… It is now time for the United States of America to own up to its responsibility to my family and to right this wrong that resulted in the loss of my beloved husband and my children’s beloved father.” Her contention is that lax safety standards at Fort Detrick enabled the attacks to occur.