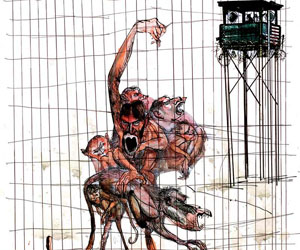

Illustration: Yuko Shimizu

As President Bill Clinton assumed office in January 1993, I held out great hope that the Immigration and Naturalization Service’s long-standing effort to deport my clients—eight people arrested in Los Angeles in 1987 for distributing magazines for a faction of the Palestine Liberation Organization—might finally come to an end. We’d begun the case under President Reagan, and continued under the first President Bush. We had consistently prevailed in the federal courts, before judges appointed by both Republican and Democratic presidents. The fbi director had admitted that none of our clients had engaged in any criminal activities, and that they were arrested only for their political associations. Surely the new Democratic administration—where some of my best friends were going to work—would abandon this ill-conceived effort?

Hardly. Instead of dropping the case, the Clinton Justice Department took it all the way to the Supreme Court, where it obtained a favorable ruling written by none other than Justice Antonin Scalia. The Clinton administration also aggressively used secret evidence to seek the deportation and detention of numerous Arab and Muslim immigrants, despite repeated court rulings that such tactics violated the Constitution. And after the Oklahoma City bombing, Clinton signed into law the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, which “streamlined” habeas corpus for all prisoners (accused terrorists or not), created a special court to remove “alien terrorists” (again using secret evidence), and made it a crime to provide “material support” to blacklisted groups, effectively resurrecting the McCarthy-era tactic of guilt by association.

So: While there may be many reasons to support Barack Obama, don’t assume that a Democratic president will necessarily transform the counterterrorism policies of the current administration. Government officials do not as a rule like to give up power, and President Bush has grabbed plenty of power for the executive branch since 9/11. Democrats in particular often feel vulnerable to being portrayed as soft on crime or terrorism, and far too many tack to the right on these issues, as Clinton did. If the problem is to be fixed—and it is essential that we fix it—it will only be because of sustained and popular pressure for change.

Don’t get me wrong. I hope a President Obama will be more attuned to civil liberties than Clinton was. And I have no doubt that Obama has historically been better than McCain in this arena. But the project is an enormous one. The list of Bush and Cheney’s insults to the Constitution could go on forever, but the low points include:

- They authorized the use of what they call “enhanced interrogation techniques,” and what the rest of the world knows to be torture.

- They asserted the right to lock up anyone anywhere in the world—even US citizens arrested at home—without a hearing, access to lawyers or the courts, or the protections of the Geneva Conventions.

- They dramatically expanded surveillance powers while bypassing judicial oversight, and ordered the National Security Agency to wiretap Americans without warrants—flaunting a statute that made such conduct a federal crime.

- They kidnapped suspects and rendered them to countries with a track record of torture.

- They disappeared other suspects into secret cia black sites, where they were subjected to brutal interrogation tactics specifically authorized in White House meetings.

- They locked up in post-9/11 “preventive detention” more than 5,000 foreign nationals in the United States, virtually all of them Arab or Muslim—not one of whom stands convicted of a terrorist offense today.

- And they asserted that when the president “engages the enemy” as commander in chief, he is for all practical purposes above the law.

Thankfully, some parts of the Constitution remain, including the one limiting presidents to two terms.

There is reason to hope that we are ready for change. A growing consensus recognizes that the Bush administration’s post-9/11 actions have not only compromised some of our most fundamental principles, but have actually made us less safe. They have made it nearly impossible to bring to justice some of the worst actors we have captured; rendered it more difficult for our allies to cooperate with us for fear that they will be tainted by our actions; and given Al Qaeda the best recruitment propaganda it could have imagined. Even President Bush admits that Guantanamo is a public relations disaster (he hasn’t quite admitted that it is a human rights disaster), and should be closed. And the administration has had to retreat on its positions on torture, unchecked presidential power, the detention of enemy combatants, and the Geneva Conventions.

Then there is the Supreme Court, which has now ruled against the administration in all four of the “terrorism” cases in which it has issued an opinion since 9/11. It found—twice—that the Guantanamo detainees have a right to challenge the legality of their detention. It rejected the administration’s claim that it could hold US citizens as enemy combatants without a hearing. It ruled that the Geneva Conventions govern the conflict with Al Qaeda, and that the military tribunals violated those conventions and US military law. And in its June decision in Boumediene v. Bush, the court for the first time ever ruled against the president and Congress acting together on a matter of national security and, in another first, extended constitutional rights to foreign nationals outside US territory. While we cannot pin our hopes on a court that is one justice away from becoming the most conservative in our history, this track record should give some backbone to those in the next administration who seek to turn the tide.

But the most important reason for hope is the remarkable job that civil society groups—from Human Rights First and the aclu to the Muslim Public Affairs Council and the Center for Constitutional Rights—have done in standing up for the principles that characterize this country at its best. By bringing lawsuits, issuing reports, holding press conferences, and mobilizing members, they have given citizens opportunities for constructive engagement with one of the most important issues of our generation—what democracy will look like in the face of the threat of terror.

It was not always so. In the McCarthy era, for example, the aclu was more consumed with purging itself of Communists than defending civil liberties—and most of the other groups doing crucial work today didn’t even exist.

Civil society, of course, is just a fancy term for “us.” It is the citizenry, mobilized. And as Judge Learned Hand, perhaps the greatest judge never to be on the Supreme Court, once said, “Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it…While it lies there it needs no constitution, no law, no court to save it.” The question is whether the audacity of this hope will give way to the politics of terror. The answer lies in us.