Illustration: Zohar Lazar

“I am a temp,” a political appointee at the Interior Department named Matthew McKeown told an annual confab of property rights activists in 2004. “I am not a career bureaucrat. I am there at the pleasure of the president, so I think that maybe puts me in some limbo category.” Bridling at what he called the “career bureaucrat mentality,” he said the president and then-interior secretary Gale Norton had been trying to “move the bureaucracy out of the way to let science govern the land again.” Through their efforts, he could happily report, “good work” was once more “on the march” in Washington. One sign of progress was the Healthy Forests initiative, a plan conservationists had dubbed No Tree Left Behind. Another involved blunting the impact of the Endangered Species Act, which McKeown described as “permanent hospice care.”

Appointees like McKeown—politically connected ideologues installed to carry out the president’s agenda—are usually swept out of power with a change in administration. But some find a way to protect their paychecks via a controversial practice known as “burrowing in.” A Washington tradition, burrowing entails transferring from a political position to a career slot (often under circumstances involving a conspicuous lack of competition) and has become such a regular occurrence that the Office of Personnel Management sends out a memo each election year warning agency heads to keep their personnel selections free from political interference. The latest version of this letter went out in March, noting that opm will review all conversions through Inauguration Day.

But this last-minute vigilance is often too little too late, says Carol Bonosaro, the president of the Senior Executives Association, whose nearly 3,000 members span the federal bureaucracy. “If you’re smart,” she says, “you do it earlier.” Such was the case with McKeown, who last year scored a $168,000 civil service job as a top legal official at Interior, a move that according to the agency “followed all of the proper hiring procedures.”

The Clinton administration left behind its own crop of ideological holdovers, and near the close of George H.W. Bush’s presidency scores of political appointees attempted to burrow, some going so far as to disguise their allegiance by taking photos of Bush off their walls. Beleaguered civil servants, meanwhile, have been known to compile “lizard” lists identifying burrowers that have a way of turning up in the hands of the incoming administration. “There’s a lot of this internal politicking that just wastes time, creates suspicion, and lowers morale,” says Vanderbilt University political scientist David E. Lewis, author of a recent book on how presidents politicize the executive branch.

There is little data on burrowing trends, but in late 2007, a team of political scientists that included Lewis and the University of Hawaii’s David Nixon conducted a survey of federal executives that asked several questions on the topic. Of the more than 2,000 officials who responded, nearly 2 percent acknowledged that they had converted from political to career jobs.

search and destroy

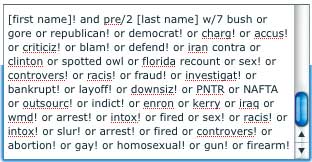

Just how much has the Bush administration politicized federal hiring? Behold the LexisNexis search string used by Monica Goodling at the Justice Department to screen applicants, as exposed in a July report from the department’s inspector general. (In the database, “w/7” searches keywords that are within seven or fewer words from the search term; “pre/2” searches the two preceding words;  an exclamation point finds word variations, so a search for “accus!” would turn up hits for “accuse” or “accusation.”)

an exclamation point finds word variations, so a search for “accus!” would turn up hits for “accuse” or “accusation.”)

—D.S.

According to an as-yet-unpublished paper by Nixon, reports of burrowing increased during President Bush’s first four years compared to the Clinton administration, and “more than doubled” after January 2006. But the data was gathered prior to April 2008, Nixon points out. “The administration’s not even over yet, so there could be a huge uptick in burrowing.” In addition, the Bush administration has widened the pool of potential burrowers, increasing the number of political appointees by some 12 percent.

As early as 2006, the Government Accountability Office reported that 144 employees in 23 agencies had converted from noncareer to career positions. In some cases, jobs seemed tailored to the strengths of the applicants, if not created for them outright. In others, standard competitive hiring procedures appeared absent. And in three instances, political staffers received career positions even though they lacked the requisite “qualifications and/or experience.”

One of those cases involved a Justice Department official named Francis L. Cramer, who in 2004 was selected to be an immigration judge (a career job, unlike politically appointed positions on the federal bench). Beyond a six-month stint in the agency’s Office of Immigration Litigation, Cramer’s only apparent qualification for hearing asylum cases was his longtime friendship with Karl Rove.

Overall, at least 30 of the nation’s more than 200 immigration judgeships were handed out through a flawed and illegal process that took into account the candidates’ political leanings and Bush loyalty rather than their experience in the field of immigration (and, an analysis by the New York Times found, many of those judges have turned down asylum seekers at a higher rate than their colleagues). “That’s the stuff that makes Teddy Roosevelt spin in his grave,” says Bonosaro, referring to the 26th president’s reform of the civil service to place merit over patronage.

Republican administrations, explains Vanderbilt’s Lewis, “have been more aggressive at the top about encouraging or coordinating” burrowing. “The evidence that we have from the ’70s and ’80s was that the Reagan and Bush administrations were very successful in changing the ideology and composition of the federal civil service.” The current White House has even managed a variation on burrowing that bypasses the political appointment process—directly seeding the civil service with ideologues whose influence may be felt for decades to come.

During the Bush years, agencies from the Pentagon to the National Park Service have been accused of politicized hiring practices. At the State Department, a political appointee in charge of a weapons of mass destruction program listed loyalty to the president as a requirement for job applicants. Similarly, a Pentagon official was found in 2006 to have selected some candidates for Iraq reconstruction jobs based on whether they’d voted for the president; he also asked some about their views on Roe v. Wade. One result: A half-dozen young, partisan officials—including the daughter of conservative foreign policy pundit Michael Ledeen, then fresh out of business school—were effectively placed in charge of Iraq’s entire budget.

But nowhere have attempts to stack the federal bureaucracy with committed conservatives been more evident than at Justice, where the political screening process was for a time overseen by Monica Goodling, the agency’s former White House liaison. Her team ran candidates’ names through Web searches (see “Search and Destroy,” above) designed to identify “good Americans.”

“This was an abuse beyond anything I’ve ever seen,” says a former senior Justice Department official, who spent more than two decades at the agency before retiring in 2005. “The Reagan administration came in with a real desire to change the composition of the career attorney corps, but they respected the hiring process. You were still getting merit-based hiring. Ashcroft threw all that out. And then it got even worse. Under Gonzales, it was just pure politics.” To an extent, he says, traditional burrowing “may be less of a concern than it normally is because they’ve already turned many of the career positions into political positions anyway.”

While Congress has begun to investigate politicized hiring, it has yet to launch an inquiry into burrowing—though some members, including Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Ore.) and Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.), have expressed concern about the practice. Reports of “wholesale” burrowing among Bush appointees would be “something we’d have a hearing on in a minute,” says Rep. Danny Davis (D-Ill.), chair of the House Subcommittee on the Federal Workforce, Postal Service, and the District of Columbia. Chuckling, he adds, “Partisanship—I think there are a lot of people who play at it. I could certainly see individuals who are political appointees being concerned about what happens to them come January. The economy is tough.”