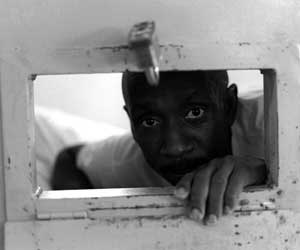

Photo: Johnny Green/PA

I hadn’t quite got used to the wordsstrungtogetherwithoutabreath speed with which The Body Shop founder Anita Roddick spoke. We had been working together on a publishing venture for less than a year; that day in the summer of 2001, she began our phone conversation with the usual “Oh hi, it’s me.” Then she switched to hyperspeed: “I’ve just heard the most amazing story and I want you to find out all about it. There are these men, and they’ve been in solitary confinement for 25 years I think. They are these incredible civil rights activists and political prisoners. They’re called the ‘Mississippi 8’ or ‘Tennessee 6’ or something like that. Our friend Sophie is a brilliant photographer and she lives in the flat next to the lawyer for these guys in Oakland. Okay, bye!” I’m not sure I managed to even clear my throat to let her know that I was in fact on the other end of the line.

I sat down at my laptop to verify Anita’s story. Google and Nexis turned up nothing on the “Mississippi 8” or the “Tennessee 6,” although I was fairly sure that I had heard of some miscarriage of justice in the South with a similar name. The West Memphis 3? Dead end.

Half a dozen phone calls finally led me to photographer Sophie Maher, who then put me in touch with Scott Fleming, a recent graduate of the UC-Berkeley law school who had taken on the case of Albert Woodfox, Herman Wallace, and Robert King—the Angola 3. Like Roddick, Fleming had come across the case by chance, via reading a letter from Wallace at a protest event; now he was working for the men pro bono.

I put together a briefing for Anita and filled in as many blanks as I could. Most of her questions I couldn’t answer, though: Why didn’t there seem to be any coverage of this? (Maybe it was the Black Panther angle that scared them off?) Was it legal to hold someone in solitary for 30 years? (I would hope not, but I had no idea.) Were they innocent? (Scott thought so.) What could we do to help them? (Get the word out maybe?)

Two months later, Fleming drove us the two and a half hours from New Orleans up through Baton Rouge and into plantation country. At the end of a seemingly interminable two-lane, the front gate of Angola prison loomed into view. “My god,” was all Anita said.

We were on the visitors list, I for Wallace and Anita for Woodfox. We passed through security, with requisite pat-downs and drug-sniffing dogs. A guard asked Anita about her accent and learned she was a Dame of the British Empire; as we waited for the bus to take us to the solitary wing of the prison, Anita regaled the guards with gossip about the royal family. It annoyed her that Americans disliked Prince Charles, and she argued in his favor. The guards, particularly the women, fell in love with her on the spot. Over the subsequent years, some recognized her on sight, squealed, and embraced her as an old friend.

We spent six hours with Woodfox and Wallace that day. Anita interviewed them as though she were David Frost, and you could tell they were both electrified and entirely confused by her.

Over the next seven years, Anita became completely dedicated to the cause of the Angola 3. She wrote articles about the case for magazines and newspapers around the world, although she remained confounded by the American press’ indifference. Anita poured the lion’s share of her energy and a good chunk of her fortune into the legal defense of the A3; several times a year, we traveled back down to the bayou for a visit.

Why was she so drawn to the case? I never fully understood, though in a sense, the Angola 3 represented a kind of perfect storm for Anita. She had been working on genocides and war crimes for a decade by then—huge, seemingly hopeless issues on a global stage. What happened at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, to her, was a very concrete encapsulation of the human rights issues she was passionate about. “They were on the bottom of everybody’s shit list,” says her husband, Gordon. “They were not getting justice or likely to.” Also, she first learned of the case through a valued family friend, who wasn’t seeking to recruit her, but only to share an outrageous story. Still, none of her engagement would have endured had it not been for that first meeting with Woodfox. “It was the human element” that clinched it, says Gordon. “It was when she first went down and visited Albert, and she came home and told me about him—and then later, when she encountered the force of nature that is Herman.”

Everything about the case was personal to Anita. During one of our trips, she was summarily ejected from the prison for visiting in the company of the one free member of the Angola 3, Robert King. Although King, who had been released from Angola less than two years before, was on the visitors list legitimately, Warden Burl Cain claimed that his presence proved that Anita was conspiring with the Angola 3. The visitors were escorted brusquely to the edge of the property, and Anita fumed. She dialed up Warden Cain as we drove away; from the backseat, I could hear the poor guy sputtering on the other end of the staticky cell phone line.

On another occasion, her book, A Revolution in Kindness, which contained essays by both Wallace and Woodfox, was banned from the prison on the grounds that it could incite violence. I think it took Anita a few hours to stop laughing.

One visit got tense when Wallace tried to bring Anita a gift of jewelry he had designed. Because it included a fist in the likeness of a black-power salute, the chief duty officer confiscated it, as well as a poem Wallace had written about his “keepers.” Things grew increasingly strained as the duty officer got on the phone to take the issue up the chain of command. While he waited for instructions, Anita did what Anita was wont to do: She told the duty officer a supremely filthy joke involving elves, penguins, and nuns. The tough guy cracked a smile, and you could feel the animosity drain out of the room. We were given another hour with Wallace and Woodfox before being asked to leave.

Anita last saw Wallace and Woodfox about a month before she died in September 2007. She was feeling tired and unwell, but was still traveling extensively. The last night we spent in New Orleans was full of great food and conversation, but there was something restive about Anita. She wanted creative, “revolutionary” strategies to get her friends out of Angola. And she was frustrated by our lack of original insight. In truth, many of us there that night, myself included, were exhausted by years of fighting without meaningful progress. Not Anita.

Gordon once said that the day Anita died, she said that her greatest priority was to see Wallace and Woodfox go free. If it happens, it will be because of her.