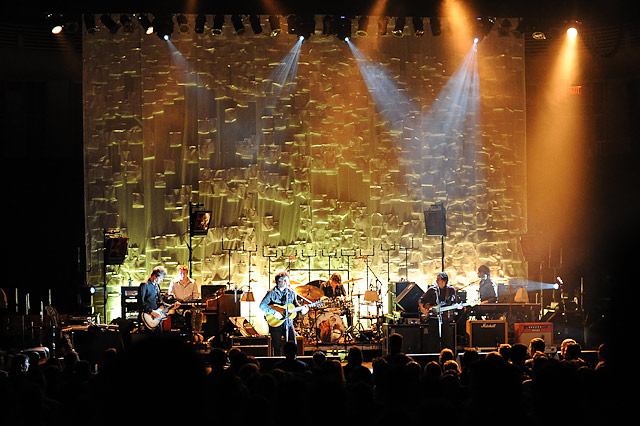

Photo from Flickr under a Creative Commons license

For three decades, the voice of Youssou N’dour, Africa’s most famous pop star, has cut through the clutter of politics. Since 1982, N’dour has put out hit records, taking a secular tack as a descendent of Senegal’s griot caste of Sufi storytellers. What he loves about his homeland, he says, is that on Fridays, “we go to the mosque, and then we go to the club.” Recently, N’dour’s appreciation for such ironies has made him the continent’s most controversial musical figure—and an award-winning sensation in the West.

Shortly after 9/11, N’dour finished recording Egypt, his first religiously themed album, but delayed its release out of concern that Westerers would associate him with terrorism. When the record finally hit the stands in 2005, it sent shock waves through Senegal’s conservative Muslim communities, inciting harsh criticism for setting religous subjects to music—something many Muslims consider profane. But the record earned N’dour a long-awaited Grammy and resounding praise throughout Europe.

Egypt‘s eight tracks are carried by strings of the Egyptian Orchestra and Senegalese percussion, and led by N’dour’s undulating voice, which floats and dives through narratives of Muslim history and triumphs against French colonialism. The first track, “Allah,” which was added for the album’s rerelease, is the most joyous. Others, such as “Tikaniyya,” named for the founder of Islam’s mystic sect, is much more mysterious, with a provocative call and response of flutes and strings.

This past weekend, I caught the San Francisco opening of a fast-paced and visually stunning documentary called Youssou N’dour: I Bring What I Love, which is currently touring the United States with a handful of international awards already under its belt. The film’s subtler moments make clear that N’dour’s fame abroad is a mixed blessing, in some sense salt in the wounds sustained by the mixed reaction from Senegal. In one scene, N’dour has an exceedingly awkward interaction with an American reporter, who, in trying to express his admiration for the music, fumbles over his words and botches his pronunciation of Sufism. N’dour thanks him, of course, but the Grammy and the international press is no consolation for rejection at home.

The film ends with little resolution about where N’dour stands with his countrymen, nor how well he is understood abroad. But in the film, the artist does retroactively gain permission from Senegal’s Muslim leaders to set Islamic themes to music, and celebrates his Grammy with President Abdoulaye Wade. At one point, a British reporter idiotically asks N’dour for confirmation of his intentions with Egypt, saying, “But it rejects terrorism?” The musician responds in so many words that that’s beside the point: The record has nothing to do with terrorism; it has to do with Islam.

And context aside, it’s worth a listen.