Illustration: Steve Brodner

ONE EVENING last October, just a few weeks before Barack Obama was elected president, more than 1,000 people crowded into a ballroom at the Ritz-Carlton in Tysons Corner, Virginia, for the “Academy Awards of government contracting.” As wineglasses clinked and Sinatra crooned in the background, a parade of executives marched across the stage to receive their accolades. After the speeches, the audience quieted for the “Contractor Hall of Fame” induction of Norman R. Augustine, the former chairman and ceo of Lockheed Martin.

“The private sector support of our government is a very important component of America’s economy and the ability of our government to perform its function,” Augustine told the crowd. “There are few greater burdens that one could bear than accepting the fiduciary responsibility of spending the public’s money.” Lockheed Martin bears a greater burden than most: Its $42.7 billion in revenue in 2008, 84 percent of it from the feds, made it the nation’s largest government contractor. Known primarily as a defense firm, Lockheed actually does business with virtually every part of the federal government, including the departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Justice, Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, Energy, and Transportation.

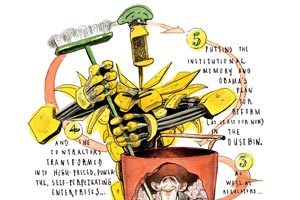

The company’s enormous reach is a window on how the past three decades have transformed Washington. To be sure, contracting has always been part of how government gets its work done. But starting in the Reagan administration (and accelerating under Clinton and George W. Bush), outsourcing turned from a means to an end: Agencies were actually required to justify why a particular job could not be done by the private sector and prove to budget officials that it was cheaper and more efficient to keep that job in-house. As a result, the federal government now employs a comparatively small number of civil servants who oversee vast armies of private sector workers—and the imbalance keeps growing as the government adds more responsibilities and more contracts. (Much of the work of bailing out and monitoring troubled financial institutions, for example, is being performed by private companies, not government experts.)

According to one of the nation’s top authorities on the civil service, New York University professor Paul C. Light, there are more than four times as many private federal contractors (about 7.6 million) than there are civil servants (about 1.8 million). Contractors perform tasks as mundane as operating lathes at US military arsenals and as sensitive as verifying the identities of immigrants seeking green cards. They teach Coast Guard personnel how to board suspect ships and they run background checks for the flight schools where some of the 9/11 hijackers were trained. In 2007, two-thirds of the 11,184 federal discrimination cases filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission were investigated by private contractors. Overseas, contractors conduct “stability operations” in Iraq and operate Predator drones over Pakistan. Back home, they run large swaths of the US air traffic control system and even handle the job of managing and auditing other contractors on behalf of the feds. In a nutshell, contractors, in many cases, are the feds: “This is the new face of government,” acknowledges Stan Soloway, who heads the most prominent trade group for federal contractors.

But now Soloway and the 330-plus companies he represents are in for the fight of their lives. The Obama administration has vowed to reform the contracting system; by the end of September, the Office of Management and Budget plans to release “tough new guidelines” that could greatly restrict the kinds of functions that can be contracted out. And the administration has even begun to acknowledge contracting’s dirty little secret: It’s expensive. Asked at a recent House hearing why military spending has grown so much faster than inflation, newly appointed DOD comptroller Robert Hale responded that “some of the costs of contractor personnel have been more than what we’re paying for federal workers.” He added that the Pentagon would seek “cost-effective ways” to bring jobs back in-house. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates has recommended that the Pentagon hire up to 30,000 new civil servants to replace contractors over the next five years, a move that could help curb the DOD’s massive cost overruns. (See “Shock and Audit.”) In April, the Pentagon killed a contract with Lockheed to process veterans’ payments, saying it would return the 600 jobs to the civil service—in part because the outsourced work had gotten too costly.

Companies such as Lockheed Martin, notes Ruth Marlin, the former executive vice president of the National Air Traffic Controllers Association, “have entire departments whose job it is to get more money out of the government. And they’re very, very effective at it.” In 2008 alone, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, the nation’s top five government contractors—Lockheed, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, BAE Systems, and General Dynamics—spent $67.5 million to lobby Congress and made about $9 million in political donations.

That K Street clout is one reason why reversing the contracting surge won’t be as easy as it sounds. More fundamentally, it turns out that many agencies are now so dominated by contractors, they literally don’t have the wherewithal to do the outsourced work without them: As I found in researching my book, Spies for Hire, more than 70 percent of the US intelligence budget—estimated this year at more than $60 billion—is now spent on contractors. Nearly 40,000 private contractors work for intelligence agencies including the CIA and the NSA, according to Ronald Sanders, a human resources official in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence; these contractors pull in salaries that average about $207,000 a year—almost double the pay of their cubicle mates employed by the government.

At the NSA, my sources estimate that at least half the jobs are contracted out. (The agency won’t disclose the official breakdown.) At the National Reconnaissance Office, the top-secret agency that manages military spy satellites, a full 95 percent of personnel actually work for contractors. At the State Department’s Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, spending on contractors soared from $115 million in 1996 to nearly $4 billion in 2008, according to data I obtained from the agency. Of that total, $2.4 billion is for contracts to DynCorp International, for training police in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Sudan. And at the US Agency for International Development, there are now roughly as many civil servants overall as were employed by USAID’s office in Saigon in 1968; much of America’s development work is now being handled by private corporations. Those contractors “talk to the senior-most officials in the Iraqi government,” one USAID official told me. “The whole paradigm has changed.” Even Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned, during her Senate confirmation hearing in January, that USAID has been “decimated.” It has “turned into more of a contracting agency than an operational agency with the ability to deliver,” she said.

The brain drain has meant that “we don’t have enough people in government to do the very high-value-added, very skilled work” called for in tasks such as financial regulation, intelligence, and contract oversight, former US Comptroller General David M. Walker told me. In the State Department unit that handles the reconstruction of Iraq (see “The Sheikh Down“), for example, civil service staffers are a distinct minority. “The institutional memory of our office is now with the contractors,” says a high-ranking foreign service officer who didn’t want his name used. “When they leave, it goes right out the door.” That’s also a serious concern at the Pentagon, according to a senior official with the Rand Corporation. “This is about the force structure of the military,” he said. Because contractors can offer better salaries than the armed services can, “we’ve created a market that’s stripping our personnel.”

Government agencies don’t even have the ability to properly oversee contracts anymore: In 2008, the Pentagon’s Office of Inspector General told Congress that while defense spending has risen to record levels, the ratio of auditors to spending has dropped precipitously, from one for every $642 million in contracting to one for every $2 billion. “As a result,” the Pentagon report concluded, “we have not been able to perform planned audits and evaluations in key intelligence disciplines.” The remaining auditors often find themselves overseeing their former colleagues or bosses. In May 2008, the Government Accountability Office found that in 2006, 2,435 former senior Pentagon officials—generals, admirals, senior executives, and contracting officers—were working for contractors. Most were employed by one of seven companies, and nearly one in five were handling contracts related to their former agencies.

Contractors, in other words, have to some extent immunized themselves against political changes. Peter W. Singer, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution who advised the Obama campaign on contracting issues, warns that “this trend has gone on so far, and the outsourcing cuts are so deep, that you have a real worry: How do you as a government get that institutional memory back? This is not something you can wave a finger at and solve in an instant.”