Photo: Jason Larkin

THE ALBERGO HOTEL, on a quiet, narrow street in the wealthy Ashrafieh neighborhood of Beirut, is a perfect place to meet a spy. The name of the street is Abdel Wahab El Inglizi—Abdel Wahab the Englishman—perhaps for an Arab who adopted English manners. Small green parrots chatter in a bell-shaped wire cage outside the entrance to the hotel, which is concealed from prying eyes by a lovely old stone wall. In the ground-floor lobby, the smell of sandalwood mixes with the pleasant decay of the leather-bound colonial library on the walls, which includes Roman histories in French translation and an ancient Encyclopedia Britannica. On one side is the reception desk; on the other, a sleepy bar. Seymour Hersh of The New Yorker spends Christmas vacations here, and members of the Lebanese Cabinet dine regularly at the fine Italian restaurant on the second floor.

Perhaps the Albergo’s most intriguing and influential habitué these days is Alastair Crooke, a former British intelligence agent who brokered deals with the IRA, funneled arms to the mujahideen in Afghanistan, spent time with rebel groups in the jungles of Colombia, and later served as Tony Blair’s eyes and ears in the Middle East. In late 2003, after three decades as a field officer, he was called home and, in classic British bureaucratic fashion, given a royal honor for his service and then fired from his job. It was rumored in London and in Jerusalem that Crooke had alienated the British prime minister by becoming too close with militant Islamists. Not long after, he reemerged as the founder of Conflicts Forum, a Beirut-based group that hosts conferences and other events under the slogan “Listening to Political Islam, Recognizing Resistance.”

Conflicts Forum has flown in former revolutionaries from the IRA and the African National Congress to teach terrorists how to be politicians. But the group’s most influential function is to give Western diplomats and intelligence types the chance to meet unofficially with representatives of Hamas and Hezbollah, Iran-backed “Islamic resistance” groups that were blacklisted by Western governments even as they gained political power in Palestine and Lebanon. “The meetings that mattered in Beirut didn’t happen at the Conflicts Forum events themselves,” one Western intelligence officer with knowledge of the meetings told me. “They happened in restaurants and hotel rooms, and in people’s apartments after the meetings.”

President Obama’s call for engagement with Iran means that the hopeful ideas behind Crooke’s back-channel dialogues will be tested against the explosive realities of Muslim societies where so-called resistance leaders are often loathed and resisted by the people they claim to represent. Candidates espousing the Islamist views Crooke admires won the Palestinian elections in 2006, but fared poorly in this year’s vote in Lebanon, and attracted substantial opposition in Iran, where members of the state security services and Basij militia murdered student protesters in the streets. “I believe there’s absolutely no evidence the election was stolen,” Crooke says of Iran. “What is paradoxically ignored in Western reporting is that this is a dispute between two sides who believe that they represent the true principles of the revolution.”

Crooke’s embrace of Islamic “freedom fighters” and power-hungry clerics attracted a fair share of criticism even before the world tuned in to the bloody images coming from Tehran. Reviewing his recent book, Resistance: The Essence of the Islamist Revolution, The Economist mocked Crooke’s “enthusiasm” for Iran’s ruling philosophy and expressed disgust at his kindly treatment of Al-Manar, Hezbollah’s TV station: “Incredibly, Mr. Crooke fails to mention that this hate-mongering station routinely pumps out vicious anti-Semitic propaganda, including a drama series that portrays hook-nosed orthodox Jews murdering gentile children in order to use their blood for Passover bread.” After attending a Conflicts Forum event featuring leaders of several radical Islamist groups, the British journalist Stephen Grey mused about “sharing jokes with the Hamas men over tiger prawns, avocado, pasta and cherry tomatoes,” and wondered how he would explain the cozy atmosphere to the mother of a child killed by a suicide bomber.

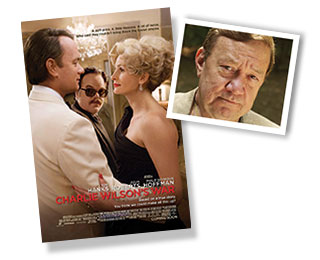

SITTING IN A high-backed chair on the top floor of the Albergo, Crooke has an oddly youthful, elfin appearance, with big ears jutting out from his head, a pointy nose, and quiet eyes that focus intently on the listener. It is a pleasant postcolonial scene, with a bowl of orchids on a low table in front of us and young Lebanese waiters moving about, lowering shades against the afternoon sun. A quote from the Koran, inlaid in silver and black on a blue background, hangs on the wall behind the old spy’s head: “The winner is the one who loves God.”

Conflicts Forum’s eclectic board of advisers includes the likes of Northern Irish politician Lord Alderdice, former Guantanamo detainee Moazzam Begg, and Milt Bearden—the legendary former CIA station chief in Pakistan who fed arms to the Afghan mujahideen during the 1980s. The group, Crooke says, was originally funded by private donations and is now subsidized in part by the European Commission, but its exact genesis and the size of its budget remain a mystery. When I ask Crooke if Conflicts Forum had anything to do with a recent decision by the British foreign office to speak with Hezbollah’s “political wing,” he gives me a genial look. “I simply can’t say,” he demurs. “They didn’t tell us.” Even some of his longtime partners in dialogue can only speculate about whom Crooke and his group represent. “We have participated in Conflicts Forum events many times,” said Ibrahim Mousawi, the media director of Hezbollah, when I asked him to describe his relationship with Crooke. “As for what Alastair is doing here in Beirut, perhaps you can tell me.”

In a tan sports jacket, navy pants, and striped shirt, Crooke could be mistaken for a wealthy horse trainer. He speaks in a soft, reasonable tone that belies the radical drift of his thoughts and the pleasure he takes in outrageous ideas. The West’s usual assessment of the Muslim world—the moderates are our Sunni allies, and the extremists are the radical Islamists aligned with Shiite Iran—is exactly wrong, Crooke says. In fact, it’s our allies, the Saudis in particular, who represent the most extreme elements, and whose Wahhabite ideology gave birth to Al Qaeda.

The true moderates in the Middle East, Crooke continues, are movements like Hamas and Hezbollah, whose driving philosophy of “resistance” (moqawama) is born of the Iranian Revolution and the more flexible intellectual traditions of Shiism. While Sunni Islam is based on a literal interpretation of the Koran, Shiite Islam is open to scholarly debate, which Crooke believes makes it more open to philosophical discourse and positive engagement with the West. He points to Hamas as an example of Sunnis who have been positively influenced by radical Shiite ideology.

Crooke views the 1979 Iranian Revolution that toppled the shah as the catalyst that shocked Shiites out of a passive approach to history and reengaged them with their philosophical roots, which they came to see as equal or superior to those of the West. The drive to extend Iran’s version of Islamic theology to the Arab world, Crooke says, offers perhaps the only way to revolutionize Sunni Arab societies, which he believes to be in a profound state of social and intellectual decay. “What they are doing,” he says of Hezbollah, “is trying to change people’s presence and move them to a different subjective reality, move them out of the Western sort of Cartesian stranglehold.” He points to the table with the orchids. “That is the real world, and the rest is fantasy and myth and mysticism.”

It is odd to hear a man who can’t speak or read Arabic or Farsi hold forth about whether a table is a table or whether that perception is a trick of Western reason that can be undone by revolutionary Islam. The weirdness of Crooke’s embrace of even the looniest doctrines of the Iranian ruling clique might indicate that Conflicts Forum is a front for Tehran. Yet the presence of American and British establishment types on the group’s board suggests otherwise. As a lifelong spy, Crooke could simply be parroting the language of the Islamic resistance to gain the trust of its leaders, while concealing his true beliefs—if indeed he has any. He is also close to Qatar’s royal family, which has both stoked radicalism and encouraged political openness in the region through its control of Al Jazeera.

Certainly, Crooke has the skilled negotiator’s ability to identify common ground. A rare glimpse of how he operates comes in a Palestinian Authority document captured by Israel in 2002, the transcript of a meeting between Crooke and four leading members of Hamas, including Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, the group’s wheelchair-bound leader, who was later assassinated by Israel. After warming up his guests with Washington gossip, Crooke declares that he believes the main problem in the region is Israeli occupation—a statement that is happily received by Sheikh Yassin, who responds that all of Israel is captured Arab territory. Yassin goes on to protest Europe’s designation of his group as a terrorist organization. “Just as you supported the fighters in Afghanistan,” he tells Crooke, “you had better support me, too.”

Crooke doesn’t miss a beat. “I completely understand what you are saying,” he replies. “As for terrorism, I hate that word,” he tells the men later, speaking of America’s reaction to 9/11. “People cannot tolerate the sight of babies being killed, and that triggers an emotional response.”

ALASTAIR CROOKE HAS always lived between worlds. He was born in Ireland, and from age 12, his parents let him attend an experimental school in Switzerland run by an Englishman named John Collette. While he chose the school for its proximity to the ski slopes, he also picked up some of Collette’s antipathy toward conventional Western thought. Crooke eschewed religious services, but “instead of being sort of sent off to watch television or something like that, they made you sit down with either an Imam or a Hindu scholar, or some visiting person, to challenge you,” he recalls. Collette “was explicit in saying, ‘Well, the effort is to break the hold of Western thinking on you.'”

Crooke’s oddball marriage of his status as a son of the British establishment with a countercultural style of thinking helped him to inhabit the distant mental realms of the extremists he dealt with. His secret work as a British go-between with the IRA was facilitated by his Irish passport and an abiding hatred of Oliver Cromwell. It’s not hard to see how he would come to view the Iranian Revolution as a good thing, a notion that could only be reinforced by watching some of the Sunni fighters he armed in Afghanistan turn their weapons against the West. It is also easy to see how a life spent making secret deals with violent men on behalf of Western governments would make Crooke cynical about official talk of human rights and democratic values.

In many ways, Crooke’s morally ambiguous relationship with gun-toting Islamists is simply the latest version of the role he has been playing all his life. On practical, political questions, he is invariably a keen observer whose perceptions of people are subtle and shrewd. He worries that the Obama administration’s moves to date show little understanding of the far-reaching consequences of a major change in America’s stance toward Iran—or the ease with which Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Israel could derail such a move.

Crooke understands today’s Middle East as similar to Sarajevo in 1914, where a random event could precipitate a cascade that changes the world. Someone will overreach—Israel, Syria, Lebanon—and then everything will shift. He reiterates this opinion when I meet him for lunch in New York. He’s in town for a panel at George Soros’ house after a trip to Washington, where State Department officials assured him that big changes were on the way. “Then when you ask what, they are not quite sure,” Crooke tells me. “We are now in an era where no one sees a direct intervention by a Western power.” This, he clarifies, means that conservative Sunnis in the Gulf states and Egypt are now free to battle it out with the Shiites in Hezbollah and Iran for the first time since the Arab nations gained their independence. “The attitude of both the US and Europe,” he says flatly, “has to be categorized as a form of denial.”

In the short term, Crooke explains, an Iranian victory in the war of ideas that divides the Muslim world would extend Iran’s power over Persian Gulf oil reserves and shipping lanes, putting Saudi Arabia in its shadow. The further empowerment of Iran would mean a profound reduction in Israel’s ability to use force against its enemies. It would also mean the end of the American-Saudi-Egyptian axis as the focal point of politics in the Arab world.

Crooke seems comfortable with all of these outcomes, in part because he believes Iran is on the right side of history. While Tehran’s rise at the expense of our Sunni allies might be disruptive and scary, Crooke implies, it’s the only way to get the relationship between Islam and the West back on a workable footing. Certainly, the idea of throwing America’s commercial ties with the Saudis and strategic ties with Egypt and Israel out the window for the sake of a romantic gamble on the Iranian regime is too much for most Westerners to stomach. Yet our current alliances with Sunni fundamentalists, Crooke warns, will guarantee that Islam remains stuck in the medieval past, and that the conflict between Islam and the West will continue. One thing that separates Crooke from more conventional, mealymouthed analysts of the Middle East is his unwillingness to understate this conflict, which he understands as a deadly struggle between two armed camps whose notions of reality are fundamentally irreconcilable.

Crooke’s argument is calculated to appeal to true believers who are willing to abandon Enlightenment ideas about human rights in favor of a distant dream of harmony between civilizations. So what if every woman living in a Muslim country has to cover her head, if students are shot dead in the streets, or if the mullahs manage to build and test an atomic bomb? It is much too early to say whether the process of engagement Crooke has nurtured will go down in history as a turning point in the West’s understanding of Islam or as yet another crackbrained attempt at dialogue with people who are not very reasonable. But it has given him an advance look at tomorrow’s headlines, which in the end is the fatal ambition of every old spy.