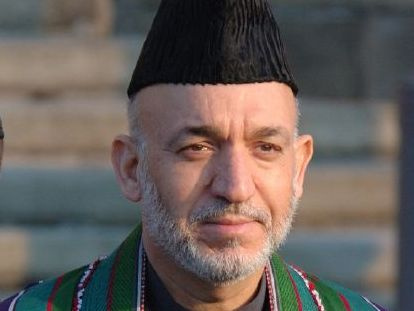

Photo by flickr user <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/opendemocracy/1552969203/">openDemocracy</a> used with a Creative Commons license.

During his recent inaugural address, Afghanistan’s embattled president Hamid Karzai dropped a major bombshell. “Within the next two years,” he declared, his administration intends to phase out “operations by all private national and international security firms” and transfer their duties to “Afghan security entities.” Coming in a speech full of bold promises, from a vow to crack down on the corruption that pervades his government to a five-year time frame for a handover of security to Afghan forces, this news was largely lost in the resulting media coverage. State Department and Pentagon spokesmen contacted by Mother Jones seemed surprised to learn that Karzai had made such an “eyebrow raising” announcement, as one put it. After all, if Karzai follows through on this pledge, it has the potential to undermine the Obama administration’s new Afghanistan strategy.

On Tuesday evening the president is expected to announce that he’s deploying as many as 35,000 additional troops to address Afghanistan’s rapidly deteriorating security situation. Though Obama has had tough words for contractors in the past, once declaring that “we cannot win a fight for hearts and minds when we outsource critical missions to unaccountable contractors,” any troop influx will likely require an increase in security contractors to guard bases and convoys, among other things. Last February, Defense Secretary Robert Gates described the use of armed contractors as “vital to supporting the forward-operating bases in certain parts of the country.”

“There’s going to have to be an accompanying increase in private security for all the activities of the new soldiers going in,” says Jake Sherman, a former United Nations official in Afghanistan who is now the associate director for Peacekeeping and Security Sector Reform at New York University’s Center for International Cooperation. “To hear Karzai talk about ramping down and abolishing private security in two years at a time when we’re awaiting a decision on the ramping up of international forces seems highly inconsistent.” He adds, “It’s ludicrous. It’s completely implausible.”

Just how many security contractors are in Afghanistan is unknown. But the Pentagon, the State Department, and the US Agency for International Development together employ at least 10,000 (many of them Afghans and so-called third-country nationals), according to figures that the agencies provided to the Government Accountability Office. (The GAO cautions that these numbers are rough approximations and may be significantly underreported.) The actual number of armed contractors in Afghanistan is likely much higher because the GAO’s tally doesn’t include security personnel working for international troops, aid organizations, private sector clients, or others.

The Congressional Research Service reported in September that “many analysts” believe high-profile controversies involving contractors—from Blackwater’s mass shooting in Baghdad’s Nisour Square to the frat-boy antics of ArmorGroup’s embassy guards in Kabul—have “undermined the US mission in Iraq and Afghanistan” by fanning hostility toward Americans and empowering insurgents. In light of this, Karzai’s attempt to phase out the use of security firms may seem like a positive step. But given the wide range of government, NGO, and private sector clients that rely on security contractors, removing them too quickly has the potential to imperil everything from aid efforts to reconstruction projects to the security of US military installations. As violence escalates in Afghanistan, demand for security personnel is only growing.

Doug Brooks, the president of the International Peace Operations Association, an industry group whose members include security companies operating in Afghanistan, said Karzai’s announcement came as a shock. “Ultimately the goal is to transition all the security over to the Afghans,” he said. “Whether it can be done in the timetable suggested by President Karzai is a bit of a question.” Privately, industry insiders are less diplomatic. Some view Karzai’s announcement as his way of hitting back at the Obama administration, after recent criticisms by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and other officials of his leadership and the extensive corruption within his government. “It was a political move to deflect all the other stuff going on,” says a security industry executive. “Karzai knows his people are not ready.”

An adviser to the Afghan government who specializes in matters related to private security companies (PSCs) told me that Karzai “does not like PSCs.” While the adviser agrees that “in the long run” it’s best to move away from the use of security operators, Karzai’s two-year time frame is “an unrealistic aspiration,” he says. “If the international troops are to stay five years then I think they will need some element of private security to support them.” Nor, the adviser says, will the US or its international partners want trained Afghan National Army or Afghan National Police diverted to routine security tasks when the main point of bolstering their numbers is to mobilize them against the growing insurgency.

Karzai’s announcement may be popular with Afghans, who have called on the government to reign in the abuses of private contractors. But the proposed ban may not bring the enhanced accountability that Afghans desire. For one, it’s not entirely clear which security operations Karzai plans to banish. “It sounds very specific when you look at the text of his speech, but there’s such nuance in terms of the private security actors on the ground,” says Sherman.

Under Afghan law, security companies must be licensed to operate through the Ministry of Interior (MOI). More than three dozen companies have received such licenses, but hundreds more firms run by local power brokers operate unregistered and unregulated. According to a recent paper that Sherman coauthored, as many as 1,500 unlicensed Afghan security outfits “have been employed, trained, and armed by ISAF [NATO’s International Security Assistance Force] and Coalition Forces to provide security to forward operating bases, escort supply convoys, and perform other functions, as well as by development agency contractors and provincial reconstruction teams (PRTs) to protect assistance projects. These security providers are frequently run by former military commanders with ethnic, political, or kinship ties to serving and former government officials and other Afghan elite. Many are responsible for human rights abuses and are involved in the illegal narcotics and black market economies.”

In fact, many security providers in Afghanistan are not companies at all, but militias. “These groups are not being formally contracted,” says Sherman. “It’s an exchange of basically a briefcase full of cash.” Even if Karzai intends to outlaw unlicensed operators and glorified militias, he may lack the political clout to pull this off. “The farther you get away from Kabul the weaker his power is,” says Sherman, which means Karzai’s plan could end up merely expelling the groups that are subject to some regulation but not those that operate without “oversight or enforcement.”

If Karzai follows through, he may simply add to the corruption he vowed in his inauguration speech to stamp out. The adviser to the Afghan government warns that Karzai’s ill-defined private security phase-out could create opportunities for “favoritism” and abuse. “I fear that elements of MOI etc. will use this as an excuse to hassle PSCs and try and receive kickbacks in order to decide who stays and who goes,” he says. “It should be across the board when it happens, not that a few connected PSCs are allowed to remain.”

Yet a consistent policy seems unlikely given that the Afghan government has historically applied laws concerning security companies unevenly. For instance, it’s technically illegal for Afghan government officials or their family members to operate security firms. But one of the biggest players on the Afghan security scene—a company called NCL that’s licensed by the Ministry of Interior—is run by Hamed Wardak, the son of the Afghan Defense Minister. Two other MOI-licensed companies, Asia Security Group and Watan Risk Management, are operated by members of the Karzai clan.

Perhaps the most disturbing example of such conflicts of interest came last June, when Kandahar’s provincial police chief, its top criminal investigator, and at least three policemen were killed in a shoot-out with a group of Afghan gunmen. Karzai’s office claimed the perpetrators were US-trained Afghan guards “from one of the private security firms,” who had staged an attack on the local prosecutor’s office in an effort to free a prisoner. Karzai strongly condemned the attack, which he said weakened the central government’s authority. Months later, the New York Times reported that the gunmen in fact belonged to a CIA-funded outfit called the Kandahar Strike Force. The group’s leader? Karzai’s half-brother, alleged drug kingpin Ahmed Wali Karzai. The incident illustrates the complex nature of Afghanistan’s security scene and the political difficulties Karzai may encounter should he attempt to shut down the most dubious operators.

This is not the first time the Afghan government has proposed banishing private security companies. According to the adviser to the Afghan government, the Karzai administration considered outlawing security contractors two years ago but ultimately shelved the plan after meeting resistance from the international community. He predicts that this time, Karzai’s proposal is also likely to encounter “push-back” centering on the “timeline but not on the overall concept.” But there are no signs of that push-back materializing just yet. Asked about the reaction of US officials to Karzai’s proposed ban, a State Department spokesman said, “He said it and all the reaction was regarding other things he said.” His conclusion? “It just sort of went through.”