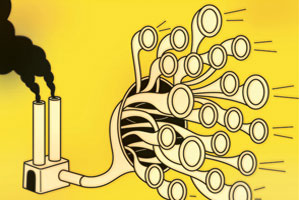

Illustration: Harry Campbell

With a name that evokes Main Street and Little League teams, and with millions of dollars to spend on lobbying, the US Chamber of Commerce has long been a powerful force on Capitol Hill. But as it’s taken more extreme positions on a range of hot-button issues, from flirting with climate change denial to fighting health care reform, its reputation as a predictable pro-business group is crumbling.

Last fall, Nike, Apple, and three major utilities quit the Chamber or its board of directors over what one company called its “extreme rhetoric and obstructionist tactics.” Companies such as Dow and General Electric distanced themselves from the group as environmental and labor groups piled on with criticism of the Chamber’s cozy relationship with special interests.

Amid the growing backlash, I reported on MotherJones.com that the Chamber had been routinely inflating its membership numbers by 900 percent—claiming 3 million businesses as members when the real number is closer to 300,000. In October, the Yes Men held a fake press conference where they announced that the lobby would now support climate legislation—leading the real Chamber to break with its stance against frivolous lawsuits to sue the anti-corporate pranksters.

The climate farce was just the most visible side of the Chamber’s larger agenda to block nearly every major reform effort in Washington. Spending as much as $300,000 a day on lobbying, more than any other group or company, the Chamber has opposed efforts to give shareholders more oversight of corporate pay, strengthen the independence of corporate auditors, and create the watchdog Consumer Financial Protection Agency. It’s trying to kill the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), which would make it easier for workers to unionize. It has run TV ads in 20 states warning that a public health care option would lead to “government control over your health.”

Even after trying to massage its bloated membership claims, the Chamber still insists that it speaks on behalf of a broad cross-section of businesses. But for the past 15 years, it’s been taking increasingly extreme, partisan stands, often setting policies in concert with small numbers of powerful donors who may not share the interests of many of the Chamber’s members.

It wasn’t always this way. The US Chamber of Commerce was founded in 1912 as a counterweight to the increasingly powerful federal government and the labor movement. Back then it generally took a moderate, nonpartisan approach, unlike groups such as the National Association of Manufacturers, which opposed efforts to expand workers’ compensation and ban child labor. During World War II, the Chamber’s president described collective bargaining as “an established and useful reality.” Half a century later, as President Bill Clinton prepared to roll out his health care plan, the Chamber’s board unanimously backed universal coverage funded by employer mandates.

For members of the Republican class of 1994, however, such consensus building was unacceptable. According to John Judis’ The Paradox of American Democracy, Rep. John Boehner (R-Ohio) told the group’s chief lobbyist that it was “the Chamber’s duty to categorically oppose everything that Clinton was in favor of.” Congressional Republicans threatened to ignore the Chamber and hinted that they might start a competing organization. The Chamber caved, reversing its position on the health plan and sending its new lobbyist to apologize to Boehner (now House minority leader).

Three years later, Tom Donohue, the hard-charging CEO of the American Trucking Association, took the wheel as Chamber president, pledging to end its days as a “sleeping giant, missing in action from many important political battles.” The group’s tone became more strident. Senior Vice President Bill Kovacs, one of a few nominally Democratic hires, said Clinton’s decision to sign the 1998 Kyoto Protocol was not simply “bad for business” but “unilateral economic disarmament.”

The Chamber’s politics became synonymous with its biggest corporate donors’. Donohue established special accounts for companies that feared taking controversial public stands, allowing them to anonymously funnel money to the Chamber, which then advocated on their behalf. In 2001, the Wall Street Journal outed Wal-Mart, Daimler Chrysler, and Merck as secret clients. (The Chamber has long refused to name any of its members.) Bruce Freed, president of the Center for Political Accountability, a shareholder advocacy group, says that the Washington head of an S&P 100 company told him that the Chamber will set up a campaign promoting a company’s pet cause if it donates at least $1 million annually.

Donohue has served on the boards of several companies that are among the Chamber’s most influential members, including Union Pacific railroad, which has given the Chamber $500,000 since 2006. Since 1998, Donohue has earned roughly $2 million in income and up to $2.2 million in stock and options from the railroad, which gets 40 percent of its business from hauling coal and staunchly opposes the Waxman-Markey climate bill. He’s expected to abide by a company policy that prevents him from acting in a way that is “inconsistent with the company’s best interests.” The Chamber has no similar conflict-of-interest policy.

Chamber spokesman Eric Wohlschlegel, who declined to comment on its climate stance and membership claims, downplays Donohue’s corporate ties, stressing that its policies are ultimately set by its committees and approved by its board of directors. But current and former members say its policy making is sometimes done undemocratically. For instance, neither the Chamber’s board nor its energy and environment committee endorsed the most controversial elements of its climate policy. “There was no vote,” says Donald J. Sterhan, the committee’s chair. The decision to challenge the EPA’s regulation of greenhouse gases, he says, came from Kovacs, who last August called for a public hearing on climate science that would be the “Scopes Monkey Trial of the 21st century.”

The Chamber claims that 96 percent of its members are small businesses, yet its self-selected board includes just 6 representatives from small businesses, 1 from a local chamber, and 111 from large corporations. Mark Jaffe, CEO of the Greater New York Chamber of Commerce, which belongs to the national group but disagrees with it on climate change and health care, tells me, “They don’t represent me.”

The more the Chamber throws its weight around to please a few large donors, the more it risks becoming just another special interest. The shift is already under way. “It’s a trade association kind of run amok,” says a Democratic Party insider who has consulted for the Chamber. After the lobby ran anti-EFCA ads that also targeted Democratic incumbents in 2008, he says, party leaders let it know that “there will be payback.” This fall, Energy Secretary Steven Chu described the defections from the Chamber as “wonderful,” and the White House openly bypassed the group to talk directly with CEOs.

Chamber president Donohue says this won’t change anything. Speaking to the Wall Street Journal in October, he declared, “People have criticized us for helping industries or individual companies. What the hell do you think we do? That’s our business!”