Following the publication of Ambassador Karl Eikenberry’s classified diplomatic cables by the New York Times, the State Department has launched an investigation into the leak of the highly sensitive documents. “We have asked Diplomatic Security here at the State Department to look into it,” P.J. Crowley, the department’s assistant secretary for public affairs, told Mother Jones on Wednesday. “We take seriously the protection of classified information and the New York Times got its hands on cables that it had no right to have.”

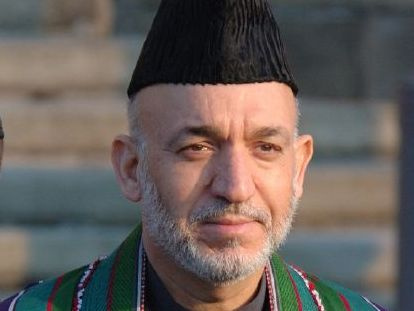

In the cables, which were described in general terms by the Washington Post and the Times last November, Eikenberry expresses serious misgivings about deploying additional troops to Afghanistan, which he believed would only increase the country’s reliance on American assistance, and he harshly criticized Afghan President Hamid Karzai. Karzai, he wrote in one message, “is not an adequate strategic partner” and he faulted the Afghan leader for continuing to “shun responsibility for any sovereign burden, whether defense, governance or development.”

According to the Times, the full versions of the memos were ultimately provided to the paper by an “American official” who believed Eikenberry’s assessment “was important for the historical record.” Foreign policy experts say the leak does the ambassador no favors, potentially complicating his already delicate relationship with Karzai. “The impact is damaging for Ambassador Eikenberry and his relationship to President Karzai and overall, possibly more broadly for US-Afghan relations depending on how these comments are seen,” said Alexander Thier, who heads the US Institute of Peace’s Afghanistan and Pakistan program. Moreover, the publication of the memos came days before the start of a high-profile conference in London that will convene on Thursday to discuss Afghanistan’s future and will be attended by both Karzai and Eikenberry, along with a host of other US and international officials. Responding to Eikenberry’s criticisms yesterday, Karzai said, “If partnership means submission to the American will, then, of course, it’s not going to be the case.”

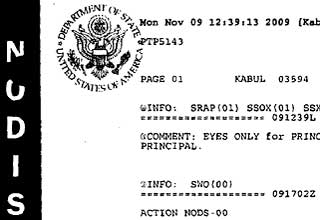

The documents that were leaked to the Times were highly classified. They were codeword protected and stamped “NODIS,” which is short for no distribution. “It’s about as careful a communication as you can send,” says Marvin Weinbaum, a former State Department intelligence analyst who focused on Afghanistan and Pakistan. “It means the only way you can read it is you have to go into a particular room and look at it and you can’t carry anything away.”

One of the cables specifies that it “may be seen only by the addressee and, if not expressly precluded, by those officials under his authority whom he considers to have a clear-cut ‘need-to-know.’ It may not be reproduced, given additional distribution, or discussed with non-recipients without prior approval of the Executive Secretariat.” Access to the other memo was further restricted. It was designated “eyes only for principal.”

The “eyes only” cable is one of four copies that were distributed to State Department officials. And the header on the version published by the Times notes that it is “SRAP Copy,” which refers to the Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, Ambassador Richard Holbrooke.

Crowley acknowledged that the cables obtained by the Times “had very limited distribution,” at least initially, but cautioned that the “original limited distribution in no way infers that the original addressees would be the source of the leak.” According to Crowley, it’s likely the number of officials privy to these documents expanded during the course of the Obama administration’s policy review on Afghanistan. “It is perfectly legitimate for the recipients or the sender of a message to share that message with those inside the policy process who had a need to know,” he said. “That’s the governing philosophy here. It’s perfectly appropriate for the distribution to expand as needed based on the importance of the information contained in the message.” He added, “My suspicion is that a copy of a copy or a copy of a copy of a copy found its way to the New York Times.”

Weinbaum said it’s indeed likely that the cables were eventually made available to a larger pool of officials. “I can believe that after [information in the memos] had gotten out the first time, at least the gist of it, that [the memos were] shared by people who perhaps shouldn’t have done so and that it was in this larger sharing process when the full text got out.” But ultimately, he said, access to these documents would still have been limited to a relatively small number of administration officials.

Leak investigations typically don’t go too far within the federal government. (The Scooter Libby case was a notable exception.) And there’s no indication whether the initial State Department inquiry will grow into a full-blown probe. But there is the potential for a major embarrassment—and that won’t make the task of implementing the adminstration’s Afghanistan policy any easier.