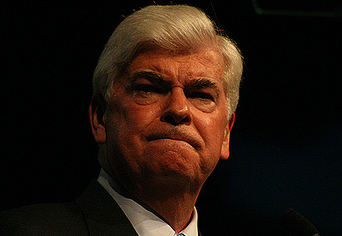

flickr/<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/arbayne/479483858/" target="new">Randy Bayne</a> (<a href="http://www.creativecommons.org">Creative Commons</a>).

The writing was on the wall for Chris Dodd in December, when even Peter Schiff, the longshot candidate in the fiercely contested Republican primary, was leading the five-term incumbent in the polls. “We have a unique opportunity,” Schiff assured supporters in December, during an appearance I attended in Watertown. Dodd “is so unpopular that just about anybody can beat him.”

Apparently Dodd and his political advisers ultimately arrived at a similar conclusion. The senator announced Wednesday that he would not seek reelection.

When I visited Connecticut last month, to take the pulse of the race that forced Dodd to seek retirement rather than suffer defeat, Republicans were practically giddy over the very real prospect of unseating Dodd. Most Democrats, meanwhile, were confident that Dodd would stay in the race—although many worried he might lose. “A lot of his ‘liberal friends’ have got wet pants now over the thought that he might not win,” John Droney, a former Connecticut Democratic party chair, told me. At the time, some Connecticut Democrats were pushing for Richard Blumenthal, the state’s longtime attorney general, to run in Dodd’s place. “As a Democrat, I want to preserve the seat, and the seat’s at risk with Dodd running,” said Nick Paindiris, who served as legal representative for the Obama campaign in Connecticut.

On Wednesday, Paindiris and other members of the “wet pants” crowd got what they wanted. Soon after Dodd dropped out, Blumenthal announced he was entering the race. A poll released Wednesday showed the AG with 30-point leads over all three Republicans.

But how did Democrats end up having to worry about losing a seat in deep-blue Connecticut in the first place?

Dodd, who was first elected to the Senate in 1980, was once considered as close to invulnerable as a politician can get. His job approval ratings were in the 60s as recently as 2007. Then the recession and the financial crisis hit. Conservatives knew that deregulation, tax cuts for the rich, and greed-is-good philosophizing couldn’t possibly be the reason for the downturn. They needed a liberal to blame.

Dodd was an easy pick. As ranking Democrat and then chair of the Senate banking committee, he was a top recipient of Wall Street campaign cash. And between 1989 and 2008, Dodd took more money than any other politician from Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two government-sponsored entities that conservatives like to blame for the collapse of the mortgage market.

The narrative stuck, and Republicans smelled blood in the water. By late November, before two candidates figured their odds were better if they switched races, there were five Republicans running against Dodd. The switches left Schiff and two more prominent candidates: Rob Simmons, a former three-term congressman (he voted for the Bush tax cuts and the Iraq War, but he still led Dodd by double digits in some polls), and Linda McMahon, the superrich CEO of Stamford-based World Wrestling Entertainment (she is reportedly willing to spend up to $50 million of her own money on the race).

Perhaps Dodd could have avoided facing a former congressman and a $50-million woman if he had voted against the Troubled Asset Relief Program. But at the end of 2008, when Bush’s treasury secretary, Hank Paulson, came begging—on bended knee, literally—for $700 billion to bail out the banks, Dodd and many other Democrats said okay. “There’s a lot of pent-up frustration,” Paindiris told me in December. “Whoever personifies Wall Street and bailouts and Washington and career politicians is going to be the victim of the general election.”

Dodd made plenty of his own mistakes, too. A quixotic run for the 2008 Democratic presidential nomination—including a temporary move to Iowa—ended in humiliation: Dodd never broke single digits.

Then, in June 2008, Portfolio magazine reported that Dodd had received a special low rate on two mortgage refinances through a VIP program for “friends” of Countrywide Financial CEO Angelo Mozilo. And last February, a Hartford Courant columnist reported that Dodd was lowballing the value of an Irish cottage he co-owned with a business partner of Edward Downe—a friend, campaign contributor, and convicted fraudster for whom Dodd helped obtain a presidential pardon in 2001. That month Dodd also inserted an amendment in the stimulus bill that would have limited bonuses at AIG and other financial firms. But when the final version of the bill appeared, Dodd’s provision had been gutted. The bonuses could be paid out after all. At first, Dodd said that he didn’t know what happened—but in March, he admitted he had made the change under pressure from the Obama administration.

But back in Watertown in December, no one was focusing on the AIG bonuses or the Irish cottage or even “friends of Angelo.” They were talking about the economy and the bailouts and their tax rates. Some of them were wondering about Barack Obama’s health care plan. They didn’t seem to care much about Dodd’s specific scandals—only the larger narrative that ties him to bailouts, big government, and the bad economy.

The problem for Republicans now is that Richard Blumenthal doesn’t fit that narrative at all. He’s been suing financial companies, not working with them. He’s not an old Washington hand. And he’s not tied down by personal scandals. Which means that the GOP’s vision of an easy victory just went out the window.