Photo of Bobby Egan and the North Korean head of American Affairs, Han Song Ryol, courtesy of Kurt Pitzer.

Read Part I: What if Kim Jong Il Went to Tony Soprano’s Dentist?

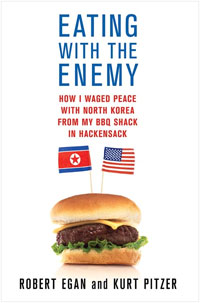

Editor’s note: This concludes our excerpt from Kurt Pitzer’s riveting new book, Eating With the Enemy, the tale of a New Jersey restaurant owner who becomes a middleman in the high-stakes diplomatic dance between America and North Korea. But you’ll want to read Part I first.

—–

“WHAT’S HAPPENING, DOC?” I could hear the alarm in my voice. “Kallis?”

The Greek ignored me and swiveled around so he was standing behind Han’s head. “Turn down the gas,” he said to his assistants. He put his hands over Han’s ears and repositioned his head and neck. “Is the oxygen ready? Turn it up.”

I was sure he knew what he was doing, but Han wasn’t a typical patient. His body wasn’t used to American pharmaceuticals. Besides the anesthetic, they’d jacked him up on a cocktail of steroids, Demerol, Ketamine, Valium and Propofol. If he stopped breathing for too long, he could suffer brain damage, or worse.

The second hand ticked around the bottom numbers of the clock on the wall. I thought: ‘I’m going to have to drag Han’s body out to the security goon and the driver and say, ‘Sorry, here’s what’s left of him.'” In which case, I’d be dead meat. Some night, an agent from Pyongyang, somebody like Cranky, would knock on my front door and rub out my whole family. And then he’d come after The Greek’s.

Han’s family might be targeted. If the regime found it embarrassing that their ambassador passed away in a dentist’s chair, his wife, daughters, parents and who knows how many other relatives could be thrown into a prison camp. I vowed that if I weren’t dead or rotting away in Leavenworth, I would find a way to help them. I’d travel to Pyongyang and grieve with them and let them know that Han’s last moments were peaceful, and that his friend was holding his hand.

A worse scenario occurred to me. What if Han died, and it led to war? In Pyongyang, the circumstances would look suspicious: The American president is threatening a preemptive strike, and the ambassador dies mysteriously in a dental office in New Jersey. That’s how the First World War started. An Austrian nobleman gets popped while driving around and minding his own business in Sarajevo and suddenly 16 million people are dead. The Greek and I would be mentioned in the encyclopedias of the future, as the guys who started a war by trying to fix a toothache. They’d call it The Molar War.

A worse scenario occurred to me. What if Han died, and it led to war? In Pyongyang, the circumstances would look suspicious: The American president is threatening a preemptive strike, and the ambassador dies mysteriously in a dental office in New Jersey. That’s how the First World War started. An Austrian nobleman gets popped while driving around and minding his own business in Sarajevo and suddenly 16 million people are dead. The Greek and I would be mentioned in the encyclopedias of the future, as the guys who started a war by trying to fix a toothache. They’d call it The Molar War.

“Come on, buddy.” I said. “Breathe for me.”

O’D poked his head into the operating room. “Are we on Headline News yet?” he asked. And before I could say, “Fuck off, Mike,” Han snorted—a drawn-out sound like kids make when they imitate pigs.

“The medication gets them too relaxed,” The Greek said. “Like apnea.”

“Could it have damaged his brain?”

“I don’t think so. Most people can go thirty seconds or more.”

Finally, after eight hours, it was time to bring Han out of the anesthesia. One of the assistants fed some wake-up juice into the IV, and Han’s eyes fluttered open. He recognized me, and looked straight into my eyes. He had a dreamy, spaced-out expression.

“I love you,” he said.

The Greek grinned at me. “He’s feeling no pain,” he said. “Not yet, anyway.”

Han turned and held his finger up to quiet everybody in the room. “I love my brother, Bobby,” he announced.

O’D shifted uncomfortably by the door. “Looks like you two need some quiet time together,” he said. “Get a room!”

The Greek and his assistants left us alone. O’D raised his eyebrows at me and followed them. Han sat on the edge of the dentist’s chair and shook his head back and forth, until he got his bearings. “Was anybody else here when I said I liked you?”

“You didn’t say you liked me. You said, ‘I love you.'”

“No, I didn’t.”

“You were petting my arm. I thought you said there were no homosexuals in North Korea.”

“Don’t even talk like that!” he said. “You are a jackass.”

I tried to help him up, but he pushed me away and stood on his own. “You gave us a good scare there, pal,” I said.

As we were leaving, The Greek slipped me a small manila envelope, which I pocketed. He tried to write a prescription for pain medicine, but Han refused it on the grounds that he needed to keep his mind sharp for the nuclear negotiations ahead.

He rolled his tongue around in his mouth. “I’m hungry.”

“You’ve been knocked out for eight hours,” I said, “you’ve earned a plate of ribs.”

“Take it easy,” The Greek said, handing me the prescription. “He’s all juiced up on steroids. Give him a milkshake, and get him the meds.”

But once Han had heard “plate of ribs,” there was no convincing him otherwise. An hour later at Cubby’s, he was pulling meat off the bone with his fingers and putting it into his mouth as gingerly as he could. If he was in pain, he didn’t show it. He was all smiles. It was too bad the new teeth were hidden by the gravestone-looking things in the front of his mouth.

“We could do something about these, too,” I said, rubbing my finger under my top lip. “I know a guy who does veneers.” Blank stare. “They’re caps,” I said. “Like gloves for your teeth. They’d make you look younger.”

Han chewed carefully on some rib meat. “I’m a bee in the beehive, remember?” he said. “I don’t need to look younger. It’s not good for me.”

“We’ll make you the Eric Estrada of North Korea!” I said. No response. “You don’t know Eric Estrada? Like a movie star. Like Tom Cruise. Think about Tom Cruise’s smile. It’s powerful.”

Han put a bare rib on his plate and wiped barbecue sauce off his fingers with a paper napkin. “Maybe it would make me a better negotiator?”

“Of course it would!” I said.

Han said he’d think about it.

MARAKOVITS WAS SITTING in the parking lot of Cubby’s when I arrived the next morning. It was Sunday, his day off. He knew. Lilia told me his agents had made 21 calls to Cubby’s while we were at The Greek’s.

“He’s feeling fine,” I said as we sat at the back table. “Everything went off without a hitch. No trouble at all.”

“I was worried, you know.” Marakovits looked like he couldn’t decide whether or not to scold me. We were still feeling out our relationship.

I pulled the little manila envelope out of my pocket and put it on the table in front of him. “If we hadn’t put him in that chair, I wouldn’t have this for you.”

He gave it a little squeeze between his thumb and forefinger and shook his head in amazement. “Is this what I think it is?” He turned it upside down and a fully intact molar rattled across the Formica. His hand shot out and saved it from flying off the table. “Does he know you took this?”

I didn’t tell Han. Even though we were like family by now, he knew we had to do our part for our own sides. Loyalties get mixed up when you reach across borders. My mom’s Uncle Tony drove a tank in WWII in parts of Italy where relatives sided with Mussolini’s fascists. When Uncle Tony’s crew fired tank rounds on the enemy, he never knew if he was hitting a cousin or an uncle.

Marakovits dropped the tooth back in the envelope, looking pleased with the trophy. It was more personal than the strands of hair I brought Kuhlmeier years earlier, and they couldn’t ask for a better body part for the purpose of identification. The tooth had been in Han’s head for four decades, chewing an unknown number of meals for him. A life of meals could be probably be detected, if anybody looked closely enough. FBI experts would examine it in some lab, I guessed. But other than Han’s diet, what would they learn from it? I wanted to tell them: Get inside the North Koreans’ heads—not their teeth and hair. Our intelligence guys seemed more interested in Han’s chemical structure than his psyche.

They could have learned something from Han’s self-image, too. Everybody likes to look good. Han wasn’t vainer than anybody else. But he wasn’t any less vain, either. A few weeks later, when his jaw had healed, I took him to Jorge Cervantes-Grundy, a cosmetic dentist in Fort Lee, who’s also a friend and a regular customer of mine at the restaurant. Grundy agreed to work on Han with zero down. Han was still leery of the idea of veneers. He asked for the yellowest ones possible. He was afraid that if his teeth looked too perfect and too white, some jealous superior back home would rip them out with a pair of pliers and send them back to America in an envelope.

Grundy installed veneers in Han’s mouth over the course of two visits in January 2003. Han looked years younger. “I’m going to Hollywood,” he boasted. “You think I can be an actor?”

“What do you want to play – the good guy or the bad guy?”

He flashed his new, killer smile. “Bad guy,” he said.

After he got his veneers, Han became a poster boy for oral hygiene. He’d grin at himself in the mirror when he thought nobody was watching. He started asking me how often I flossed and telling me I needed to get my bottom teeth straightened.

Despite the Communist system that says they have to live for the glory of their nation and all that BS, I’ll bet most North Koreans would jump at the chance to get their teeth fixed. I imagined a dental-diplomacy effort, starting with the Dear Leader and his top brass and working our way down the chain of command. I talked to The Greek about it, and he offered to make a humanitarian trip to Pyongyang anytime I asked. I had conversations with Bill Henry and Han about getting dental lab equipment shipped over there, with the idea of opening up a clinic.

They say the little details of your appearance can have a psychological effect on how others see you. Especially the teeth. I’ve heard that looking at someone’s teeth is how we unconsciously measure their vitality. The mouth is the gateway to health, they say. Han was always talking about juche and self-reliance. To me, self-reliance starts with self-improvement. Or to put it in terms of politics, if you can’t change your adversary, change yourself. I wasn’t saying dental work alone would do the trick. But most of the North Koreans I met had plenty of room for improvement in the oral-cavity department. A few fixes in that area could help their self esteem. Imagine what could happen if a group from Pyongyang showed up to a negotiating session and flashed their new and more pleasing smiles—winning smiles—at their American counterparts. The Americans would smile back. It’s instinctual. Things like that work on an unconscious level. Maybe the negotiations would take on a better tone. You never know. Sometimes it’s the intangibles that make all the difference.