Argonauts (Cephalopoda: Argonautidae) are a group of rarely encountered open-ocean pelagic octopuses with benthic ancestry. Female argonauts inhabit a brittle ‘paper nautilus’ shell, the role of which has puzzled naturalists for millennia. The primary role attributed to the shell has been as a receptacle for egg deposition and brooding. Our observations of wild argonauts have revealed that the thin calcareous shell also functions as a hydrostatic structure, employed by the female argonaut to precisely control buoyancy at varying depths. Female argonauts use the shell to ‘gulp’ a measured volume of air at the sea surface, seal off the captured gas using flanged arms and forcefully dive to a depth where the compressed gas buoyancy counteracts body weight. This process allows the female argonaut to attain neutral buoyancy at depth and potentially adjust buoyancy to counter the increased (and significant) weight of eggs during reproductive periods. Evolution of this air-capture strategy enables this negatively buoyant octopus to survive free of the sea floor. This major shift in life mode from benthic to pelagic shows strong evolutionary parallels with the origins of all cephalopods, which attained gas-mediated buoyancy via the closed-chambered shells of the true nautiluses and their relatives.

She is bobbing through the calm waters inside the barrier reef, near the swift channel between two hoa (passes), where a pair of streams enter the sea. I am loitering in the calmer water myself, dipping and fluttering my canoe paddle and trying to steer a straight course. It’s just after dawn. The air has not yet awoken to the convection currents that will drive it later this day, and the lagoon is motionless, almost oily looking, with a glycerin sheen as absorbent to color as a paintbrush. In the ripples to my left, the peridot green of Mount Rotui blooms. In the ripples to my right, the obsidian blue of the open sea. Between the two lies a surface as good as a window, through which sergeantfish, anthias, and lionfish drift above little islands of corals and gatherings of stingrays.

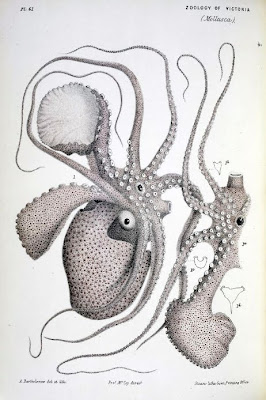

From afar, she looks like one of those ubiquitous pieces of oceangoing flotsam washed from shore or ship and plying the ocean with indestructible endurance. I paddle towards her, bent on litter collection, only to discover that she is not a styrofoam cup or a plastic sandal but a living creature roaming inside her own home—an argonaut, or paper nautilus, probably of the species Argonauta argo. She is a member of a genus of octopus that long ago abandoned life on the seafloor in favor of roaming the open seas. Unlike her namesake, the chambered nautilus, her delicately coiled shell is not an external skeleton that she is attached to as we are to our fingernails, but a mobile home that she can come and go from like a hermit crab.

I have never seen an argonaut alive in the sea before, and with fumbling hands I don mask, snorkel, and fins and slip over the side, dragging the va’a canoe by the float so as not to lose it. She is a timid creature and this may be the only opportunity that ever comes my way to see her in the wild. The thought going through my mind as I waft my fins is that I must approach as softly as a ripple.

It doesn’t matter though. She is engaged in one of those acts of violence that nearly preclude thoughts of personal safety. She is half out her shell, pulsing in bright red and yellow, the colors literally tumbling through her like reflections from flashing police lights. Her colors are so strong they bleed beneath the skin of her paper-thin shell, bruising it. She is administering the coup de grâce to a pteropod, a sea butterfly. Her eight arms are flared open, an umbrella turned inside-out, exposing the parrotlike beak. The pteropod is flapping its transparent wings in hopes of escape but the argonaut is reeling it in on the sucker disks of her arms, biting it, then tucking it under her bell, and rolling herself back into her translucent shell, where the flames of her hunting colors soften to pink.

Quietly now, her big eyes innocently wide, she floats a foot below the surface, arms wrapped over her head, the tips of them tucked daintily into her shell, leaving most of her sucker discs exposed. She observes me from a safe distance, one orange eye watching as she feints towards shore, the other watching as she tacks towards her home in the open sea.

As with every female argonaut octopus, she has fabricated her shell herself, using calcium carbonate secreted by the two large, flattened dorsal tentacles unique to her genus and gender. She has invited a much smaller—no more than an inch long (invisible to me)—father-to-be aboard. Now, with her head and tentacles protruding, she sails herself, her mate, and eventually her brood around the tropical and semitropical oceans of the world. Carrying the family on the currents, her shell is as fragile as a parasol of bone china, yet strong enough to shield its occupants from the ultraviolet radiation present near the surface of the oceans.

Lithograph of Argonauta nodosa, The Tuberculated Argonaut, or Paper-Nautilus, Argonauta oryzata; Artist: Arthur Bartholomew (1870s). Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.