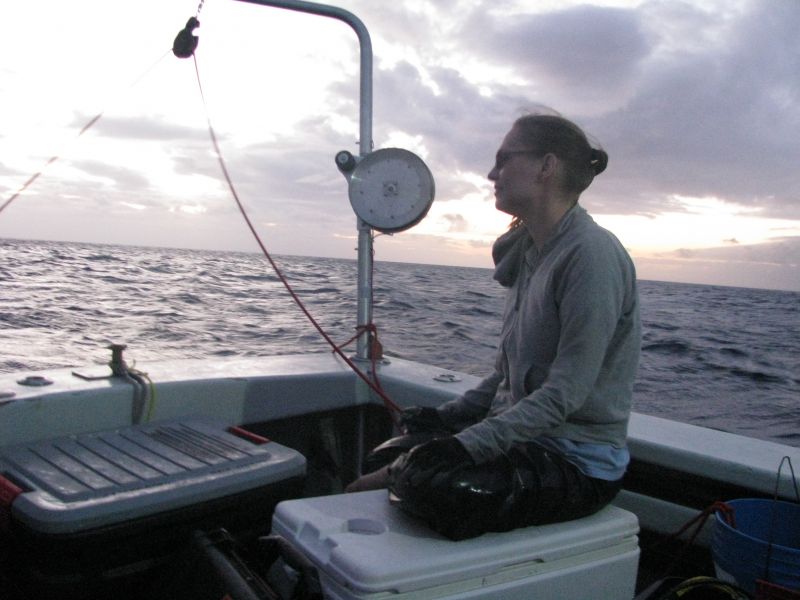

Kelly Benoit-Bird at work as night falls off Hawaii. Photo © Julia Whitty.

I had fun sailing with Kelly Benoit-Bird in April and helping out with a small portion of the research she and Margaret McManus are conducting off Hawaii. They’re studying—through sound—the behavior and ecology of the the ocean’s deep scattering layer. I featured Benoit-Bird and her work in my cover article for this month’s Mother Jones, BP’s Deep Secrets. The deep scattering layer—with its aggregation of fishes, squids, crustaceans, and other dark-sea dwellers—have likely been hard hit by BP’s oily freight train run amuck in the Gulf of Mexico.

It was with real pleasure I learned that Benoit-Bird has won one of this year’s MacArthur fellowships. I can hardly imagine anyone more deserving. Since we first met her in her office at Oregon State University a couple of years ago, I was seriously impressed with her amazing intellect and vision—the likes of which enable her to think far outside the scientific paradigm to intiate new research. Her phenomenal brain also enables her to develop new tools, or modify old tools, to pursue her investigations. That’s a rare combo.

Here’s the MacArthur video of Kelly explaining her work.

The MacArthur Foundation page describes Kelly as a marine biologist who uses sophisticated acoustic engineering techniques to explore the previously invisible behavior of ocean creatures at scales ranging from swarms distributed over many cubic kilometers to individual predators:

Although zooplankton drift in response to ocean currents, Benoit-Bird has shown that they use their modest locomotive capacity to form swarms with distinct three-dimensional structures that change with feeding conditions. Using multi-frequency acoustic backscattering, she has been able to reconstruct the feeding patterns of swimming predators of zooplankton (known as nekton) as they first pass downward through a layer of zooplankton, then reverse course and pass through upward. Having precise data about the horizontal and vertical distribution of oceanic food webs opens a new path for understanding the complexities of marine ecology. Further up the food chain, Benoit-Bird has investigated and illuminated the behavior of mammalian predators such as spinner dolphins, which hunt nekton in small, coordinated groups. These groups follow a carefully choreographed sequence of movements, repeated many times, to minimize the opportunity for the prey to escape. Using advanced acoustic engineering technology that she has modified and optimized for applications specific to her research, Benoit-Bird is addressing long-unanswered questions and providing the marine ecology community with a clearer picture of the structure and behavior of food chains.

If you want to see the übercool data animations of Kelly’s spinner dolphin work, check this out. The explanation can be found on this page, as a supplement to her paper:

Benoit-Bird, K.J. & Au, W.W.L. 2009 “Cooperative prey herding by a pelagic dolphin, Stenella longirostris.” Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 125: 539-546.