Photo by ?.????, courtesy Wikimedia Commons

A sampling of the latest science papers. Forthwith: Lizard families form multigenerational dynasties; Extinct passenger pigeons speak through DNA; 2008 volcanic eruption fertilized North Pacific; Volcanic eruptions 40,000 years ago doomed Neanderthals and enabled rise of an upstart pipsqueak, Homo sapiens.

- Researchers at the University of California Santa Cruz found that desert night lizards from the Mojave Desert live in family groups and show patterns of social behavior more commonly associated with mammals and birds. Desert night lizards are unusual among reptiles in that they’re vivparous, giving birth to live young. They also huddle in groups through the winter beneath fallen Joshua trees. Genetic analysis revealed the huddling groups are made up of related individuals. Five years of study showed that young desert night lizards stay with their mothers, fathers, and siblings for several years after birth. Some groups aggregate under the same fallen log year after year, forming dynasties. The investigation provides new insights into the convergent evolution of cooperative behavior. The paper, Convergent evolution of kin-based sociality in a lizard, appears in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B .

- DNA extracted from 100-year-old museum specimens reveals extinct passenger pigeons were less closely related to New World mourning doves, as formerly believed, and more closely related to New World pigeons. Biogeographic analysis suggests they may have colonized North America from Asia and dispersed into South America. Passenger pigeons were entirely nomadic, forming huge flocks and breeding colonies, millions strong. They were the most abundant birds on the planet. In the early 1800s, flocks were vast enough to take days to pass overhead, literally darkening the sky. Nothing in modern times compares. Passenger pigeons were also one of North America’s first birds driven to extinction at human hands. The paper, The flight of the Passenger Pigeon: Phylogenetics and biogeographic history of an extinct species, appears in Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution.

-

The 2008 eruption of the Kasatochi volcano in the Aleutian Islands spewed iron-laden ash over a large swath of the North Pacific. The result was an ocean productivity event of unprecedented magnitude—the largest phytoplankton bloom detected in the region since ocean surface measurements by satellite began in 1997. Yet the bloom resulted in only a modest uptake of atmospheric CO2. The paper, Volcanic ash fuels anomalous plankton bloom in subarctic northeast Pacific, is published in Geophysical Research Letters.

-

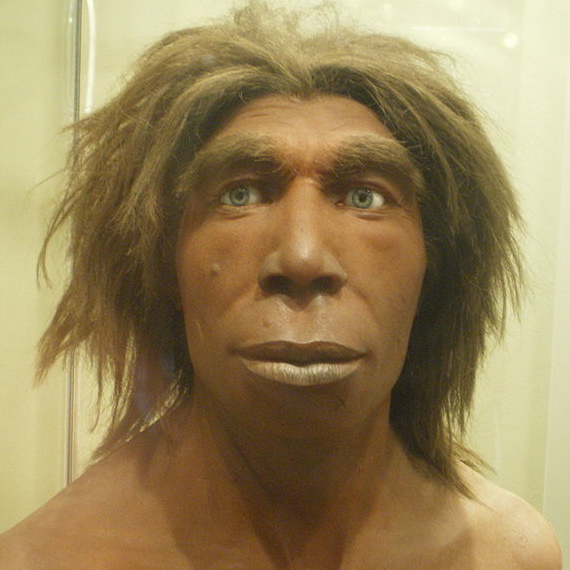

New research suggests that climate change following massive volcanic eruptions drove Neanderthals to extinction and cleared the way for modern humans to thrive in Europe and Asia. These eruptions caused a “volcanic winter” as ash clouds obscured the sun’s rays, possibly for years. The paper, Significance of Ecological Factors in the Middle to Upper Paleolithic Transition, appears in the October issue of Current Anthropology. From the abstract:

For the first time, we have identified evidence that the disappearance of Neanderthals in the Caucasus coincides with a volcanic eruption at about 40,000 BP. Our data support the hypothesis that the Middle to Upper Paleolithic transition in western Eurasia correlates with a global volcanogenic catastrophe. The coeval volcanic eruptions (from a large Campanian Ignimbrite eruption to a smaller eruption in the Central Caucasus) had an unusually sudden and devastating effect on the ecology and forced the fast and extreme climate deterioration (“volcanic winter”) of the Northern Hemisphere in the beginning of Heinrich Event 4. Given the data from Mezmaiskaya Cave and supporting evidence from other sites across the Europe, we guess that the Neanderthal lineage truncated abruptly after this catastrophe in most of its range. We also propose that the most significant advantage of early modern humans over contemporary Neanderthals was geographic localization in the more southern parts of western Eurasia and Africa. Thus, modern humans avoided much of the direct impact of the European volcanic crisis. They may have further benefited from the Neanderthal population vacuum in Europe and major technological and social innovations, whose revolutionary appearance shortly after 40,000 BP documents the beginning of Upper Paleolithic.