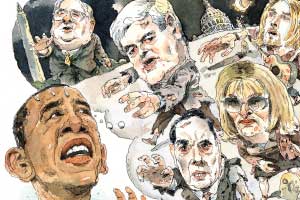

Illustration: John Cuneo

A few weeks before the midterm election debacle, the White House received an ominous signal. Seven Republican senators issued a letter asking for an investigation of President Barack Obama’s top economic adviser, Austan Goolsbee. During a background briefing call with reporters, Goolsbee had casually referred to what he believed was the tax status of Koch Industries to make a point about companies that duck corporate taxes. Because the billionaire Koch brothers have financed much anti-Obama political activity, conservatives immediately suspected something more nefarious: that Goolsbee had rifled through confidential IRS records to dig up information on political enemies. Calls quickly came for a full-fledged investigation. The IRS inspector general told the senators he would review the matter, and the episode faded from public view. But what if the get-Goolsbee Republicans had been in control of a chamber of Congress? They could have launched their own investigation, issued subpoenas, demanded information from the White House and the IRS. Goolsbee would have been forced to lawyer up. He and his colleagues would have been preoccupied with a congressional probe, rather than the country’s economic woes.

Starting in January, such a scenario is entirely possible. Republicans, in control of the House, will be able to pursue whatever probes they desire. How might they handle such power? For a clue, we have to look back into the mists of history—all the way to…the 1990s. With the tea partyized GOP now in charge, it may well be back to the future in Washington.

After Newt Gingrich led the Republicans to a historic victory in the 1994 elections, GOPers controlling the House and Senate viewed the Clinton White House as investigative chum. With the right wing pushing a variety of conspiracy theories—religious right leader Jerry Falwell actually peddled a video that accused Bill Clinton of involvement in drug smuggling and various murders—House committee chairs began a flurry of free-wheeling investigations of the administration. There was Travelgate (about cronyism in White House hiring). And Filegate (about the handling of FBI files on prominent politicos). And Whitewater (about the Clintons’ Arkansas land deal). Rep. Dan Burton (R-Ind.), the erratic chair of the House government oversight committee, became so obsessed with the suicide of White House lawyer Vince Foster—whom a handful of right-wingers suspected had actually been bumped off because he knew too much about the Clintons’ supposed sleazy dealings—that he reportedly reenacted the shooting in his backyard using a pumpkin, melon, or some other head-shaped produce. At one point, Burton, who openly referred to Clinton as a “scumbag,” released heavily edited tapes of an imprisoned former administration official that falsely suggested the inmate was spilling the beans on unspecified Clinton wrongdoing.

Even when Republicans had cause for real investigation, they couldn’t help but go around-the-bend crazy. Following the 1996 election—which was marked by fundraising improbity on both sides—House and Senate Republicans mounted separate investigations of White House fundraising. (Recall Coffeegate, the Lincoln bedroom sleepovers, and the Buddhist temple fundraiser [PDF] controversy.) Burton stuck to his usual antics, but even the more responsible Fred Thompson (R-Tenn.)—then chairing the Senate government affairs committee—was snared by the atmosphere of reckless speculation. He opened the Senate hearings claiming that the Chinese government had a plan to “pour illegal money” into the 1996 campaign “to buy access and influence” at the Clinton White House. The hearings put the spotlight on GOP and Democratic Party fundraising shenanigans, but never produced proof of a Chinese conspiracy.

And, oh yes, Monica madness.

For all the Republican mudslinging, Clinton won reelection in 1996. And Hillary went on to be elected a senator in 2000. But the subpoenapalooza did fulfill a strategic aim of the Newtites: It pinned the White House down. Burton issued 1,052 subpoenas to the executive branch and congressional Democrats from 1997 to 2002. “The amount of time and energy spent responding to subpoenas was massive,” recalls Don Goldberg, who was a Democratic House aide in the 1990s and then a staffer for the White House’s damage control team. “It shut everything down. It tied the White House in knots.” And that was before the impeachment crusade.

The Republicans of that day were not merely partisan pugilists; they were ideological firebrands, pushing a fierce conservatism, decrying the moderates of their party who had dared to compromise with the other side. So committed were they to advancing their high-octane conservatism that when Clinton would not agree to a budget with severe spending cuts, Gingrich and his allies—rather than yielding—precipitated two government shutdowns that came to be widely regarded as political suicide for the GOP.

Let’s see: anti-government ideologues, backed by grassroots activists yet funded by corporate political donations, willing to gum up the works and raring to use subpoena power to pursue conspiratorial accusations against the president. Sound familiar? Is Billy Ray Cyrus poised for a comeback, too?

But there are differences. If anything, the new GOP House majority is probably more conservative than the Republicans of the 1990s. Yet its leaders—including presumed speaker-to-be John Boehner, who was part of the Newt Revolution and witnessed its collapse—may be savvier in calculating how far it’s safe to go in opposing the president and appeasing their right-wing base. Rich Galen, who was once Gingrich’s press secretary, says Boehner “has a better feel for what needs to get done and how to get things done than what Newt had. Newt couldn’t separate being speaker from the revolutionary skills that got him there. Boehner is more a creature of the House.” Gingrich, Galen points out, saw himself as a “transformational leader” and desired to be “the opposer-in-chief.” Boehner has a more modest self-image.

But can Boehner keep the lid on the crazy? Rep. Michele Bachmann (R-Minn.), who is expected to lead a beefed-up House tea party caucus, last year called for investigations of “anti-American” Democrats in Congress. Then there’s Rep. Darrell Issa (R-Calif.), who is slated to take over the government oversight committee, a panel with tremendous authority to probe the administration. Last May, he said that the White House’s offer of a nonpaying job to then-Rep. Joe Sestak (D-Pa.)—presumably to keep Sestak out of the Pennsylvania Senate race—might be an impeachable offense. Seven GOP members of the Senate judiciary committee joined (PDF) Issa in calling for a special prosecutor to investigate the Sestak affair.

When the new Congress convenes, Issa could issue subpoenas about Sestakgate—or anything else. The day after the election, Issa announced his intent to examine the Bush and Obama administrations for how each handled the mortgage crisis and problems with offshore drilling oversight at the Minerals Management Service. He’s also signaled that he wants to whip up investigations of several tech-related ethics issues at the White House—perhaps the use of smart phones by Obama aides and whether they are complying with presidential-records laws. Issa, who has called Obama “corrupt,” has clearly signaled his target will be the administration, not corporate wrongdoers: “I won’t use [subpoena power] to have corporate America live in fear that we’re going to subpoena everything. I will use it to get the very information that today the White House is…not producing.” Meanwhile, Gingrich has urged House Republicans to go ahead and force a shutdown of the government over funding of the health care reform law: “I think this city has fundamentally misunderstood what happened with the [1995] shutdown. To most of the country, it became a signal that we were serious.”

So is now a good moment to brush up on Seinfeld lines? History, of course, never fully repeats. Obama, Democrats can expect, will not become involved in a sex scandal that drives Republicans to such extremes that voters get ticked off—as they did during Monicagate, when they rallied behind Clinton and recoiled from Kenneth Starr’s too-much-information report. In the end, Democrats benefited from a deterioration of the Republican brand that began with the excesses of the 1990s. Perhaps it is time to pop Groundhog Day into the VCR and repeat after Bill Murray: “Anything different is good.”