Photo: NOAA.

A 13-year-old western Pacific gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus) is shining some light on the travels of his kind.

Flex—as he’s called by researchers—was tagged on 4 October on his summer feeding grounds in the Okhotsk Sea off Sakhalin Island, Russia.

Western Pacific gray whales are among the most endangered whales on Earth, with a population of only 113 to 130 individuals. In contrast, the gray whales who migrate along the western coast of North America—known as the eastern Pacific gray whales—comprise a population estimated at between 15,000 and 22,000 individuals.

Gray whale. Photo by Jim Borrowman, Straitwatch, courtesy NOAAThe good news is that as recently as 1972 Flex and the western grays were believed extinct. Still, the margins are thin. The IUCN Red List categorizes the western grays as critically endangered—the last stage before extinction:

Gray whale. Photo by Jim Borrowman, Straitwatch, courtesy NOAAThe good news is that as recently as 1972 Flex and the western grays were believed extinct. Still, the margins are thin. The IUCN Red List categorizes the western grays as critically endangered—the last stage before extinction:

[B]ased on an extinction probability exceeding 50% within three generations, or a projected continuing decline of the subpopulation in combination with a mature population size less than 250. In addition, the small absolute subpopulation size, and the estimate of at most 35 reproductive females means that the subpopulation would easily qualify as Endangered.

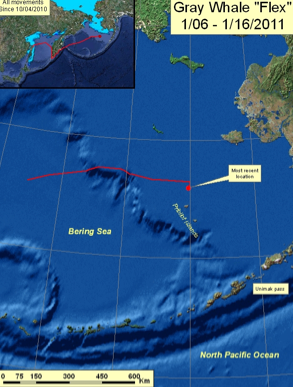

“Flex” departed the Kamchatka coast on 3 January and took one week to cross most of the Bering Sea before arriving at the slope edge of the eastern Bering Sea shelf on 9 January. Since 3 January, he has covered 1,689 kilometers/1.049 miles in 238 hours for an average of 7.09 kilometers/4.4 miles an hour. Since attaining the slope edge, he has trended to the south, toward the Pribilof islands. During the last several days we have obtained individual transmissions during several orbits, so we know the tag is still attached and functioning, but not enough transmissions to obtain reliable locations. Some of this may be due to regional bad weather.

Over the course of a 10-year longitudinal study, banded birds produced 39% fewer chicks and had a survival rate 16% lower than non-banded birds, demonstrating a massive long-term impact of banding and thus refuting the assumption that birds will ultimately adapt to being banded. Indeed, banded birds still arrived later for breeding at the study site and had longer foraging trips even after 10 years. One of our major findings is that responses of flipper-banded penguins to climate variability (that is, changes in sea surface temperature and in the Southern Oscillation index) differ from those of non-banded birds. We show that only long-term investigations may allow an evaluation of the impact of flipper bands and that every major life-history trait can be affected, calling into question the banding schemes still going on. In addition, our understanding of the effects of climate change on marine ecosystems based on flipper-band data should be reconsidered.

UPDATE: Bruce Mate, Director of the Marine Mammal Institute, fills me in on the gray whale tagging program:

The tagging of western gray whales was preceded by an efficacy study on the much more common eastern gray whales in 2005 and 2009. The latter was on the “resident” summer gray whales feeding here in the Pacific NW, with lots of follow-up photographs to look at “wound healing”. These photos have been reviewed by a group of three marine mammal specialist veterinarians, who felt there were no major impacts and that what they saw caused them “no concern, These results were reviewed by whale specialists at the IWC and IUCN, who approved the results before we tagged western gray whales.

Meanwhile, stressors on western gray whales are growing. The Anchorage Daily News reports that in the past four years five females have died entangled in fishing gear.

And just yesterday the World Wildlife Fund announce that Sakhalin Energy Investment Company—partly owned by Shell—has announced plans to build a major oil platform near crucial feeding habitat of the western grays in waters already besieged by multiple oil and gas exploration and development projects. The company will conduct a controversial seismic survey this summer. WWF states their concerns:

“We still do not know how badly the whales were affected by major seismic activity last summer—and will not know until the whales return to their feeding grounds again this year and scientists can determine if any are malnourished. It is totally inappropriate for Sakhalin Energy to plan another seismic survey in 2011 before we have the opportunity to examine the health of the animals,” said Doug Norlen, Policy Director at Pacific Environment.

Other concerns regarding another offshore platform:

- Potentially disrupting the whales’ feeding behaviors

- Increasing the chance of fatal ship strikes

- Increasing the risk of an environmentally catastrophic oil spill on the whales’ feeding grounds

You can follow Flex’s travels here. The site is updated weekly.

- Claire Saraux, et al. Reliability of flipper-banded penguins as indicators of climate change. Nature. 2011. DOI:10.1038/nature09630