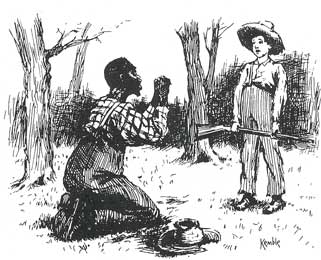

Illustration: The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Should a bowdlerized version of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn be taught in high school English classes? As the only African-American student in my English class when this book was assigned, I can assure you that 219 repetitions of the word “nigger” were discomforting at best. But I don’t entirely agree with MoJo blogger Kevin Drum‘s take on NewSouth Books’ forthcoming censored Huck, which replaces “nigger” with “slave.” Writes Kevin:

The problem with Huckleberry Finn is that, like it or not, most high school teachers only have two choices these days: teach a bowdlerized version or don’t teach it at all. It’s simply no longer possible to assign a book to American high school kids that assaults them with the word nigger so relentlessly.

I sat down with Mission High School English teacher Tadd Scott this week to see what he—an African-American teacher in a primarily non-white high school—had to say about teaching Huck Finn. (He assigned it when he taught American Literature to high school juniors and seniors.)

How did he deal with the text? Well, students weren’t allowed to say the word “nigger” in his classroom anyway, he explains. Instead they skipped over it or used the “N-word” phrase instead when talking about the book.

But how did they feel about the word itself in the text? Students were offended by it. “It’s like ‘faggot’ and other horrible, demeaning words,” he says. Still, he doesn’t think the text should be rewritten. “I’m an artist,” he says. “I don’t believe in changing someone’s art. Leave it as it is.” If the goal is to introduce students before college to Mark Twain’s writing, he advises teaching Tom Sawyer excerpts or The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County. If it’s to introduce high school students to the realities of slavery, assigning slave narratives like this one would be a better choice.

Besides the “n-word,” NewSouth Books is also changing the word “Injun Joe” to “Indian Joe” and “half-breed” to “half-blood,” which this Native American blog discusses. But there are plenty of reasons—other than the book’s inclusion of historic slurs—why English teachers could choose to teach other texts in American Literature classes, Scott explains. “Who was Huck Finn written for? At the time, it was written for a largely white male population, maybe a few women got it. But America right now is not white, it’s multicultural,” he says. “So ‘American literature’ should probably reflect that.” One American Lit option he recommends is Langston Hughes’ Mulatto: A Play of the Deep South, the first black play performed on Broadway. Another choice: Black Boy, by Richard Wright. Both have been well-loved by his students, he says.

Scott remembers reading Huck Finn when he was 15 as a black student in a mostly white class. “All my teachers of English were white men and white women, and maybe they didn’t have the background to understand. But I never saw great black women or men writers during my high school experience, and I do know that I want my people to see themselves in literature in a wonderful way.”