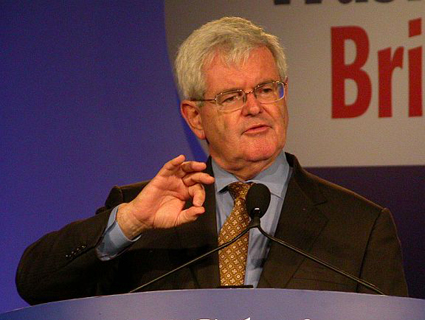

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

On Wednesday, former Republican Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich kicked off his presidential exploratory committee with announcements on Twitter, Facebook, and Fox News. He’s in it to win it: In 2009 and 2010, Gingrich raised more money than all of the other candidates combined. With his deep network of PACs and business ventures, the former Speaker has the resources to go along with the strong name recognition. But Gingrich still faces a serious adversary—his record. On everything from medical marijuana, to marriage, to Libya, Gingrich has a long history of making incendiary statements that bely his own actions. Take, for example, his campaign to weed out wasteful spending.

In his 2009 book, Real Change, Gingrich singles out Lockheed Martin and NASA for squandering taxpayer dollars on faulty equipment for the agency’s Mars program. The ballooning costs and endless delays, he explained, were emblematic of the “kinds of waste and fraud that currently plague government programs.” As he put it: “These cumbersome, bureaucratic companies can match the federal government’s expertise in red tape… What matters is not the quality of their engineering, but the quality of their lobbying.”

Rather than funneling money into a company operating with little oversight, Gingrich argued, we should let the marketplace place do the work, and hold prize competitions for new technologies.

It’s not a terrible idea—in fact, it’s similar to the plan put forth by President Obama two years ago. But there’s just one problem with Gingrich’s framing: During his two decades as a congressman from Georgia, representing a district adjacent to a major Lockheed assembly plant*, there was no bigger advocate for the contracting giant’s “cumbersome, bureaucratic” business interests than Newt Gingrich.

The relationship began early. As a freshman congressman from suburban Atlanta in 1979, Gingrich drafted a letter to President Jimmy Carter, lobbying for the sale of L-100 Hercules jets to Muammar Qaddafi’s Libya. Although Gingrich now says that Qaddafi has been an enemy of the United States since the early 70s, and supported (for a moment, at least) military intervention in North Africa, the congressman’s focus at the time was pure retail politics. Boeing had been allowed to sell three similar planes to the dictator, he told the president; why shouldn’t Lockheed?

For the most part, though, Gingrich’s hawkish foreign policy positions dovetailed nicely with his interest in filling Lockheed’s coffers. He spent much of the 1980s lobbing rhetorical bombs about the existential threat posed by the Soviet Union and supported President Reagan’s escalations in defense spending even though they led to an ever-increasing deficit.

Speakers traditionally avoid serving on any congressional committees, not only because of the undue influence they’d command, but also because of obvious time constraints. Gingrich made an exception when he acquired the gavel in 1995. One of his first orders of business was to appoint himself to the House intelligence committee. He filled the roster with up-and-coming GOPers who knew better than to cross him, and used his influence to ensure that none of Lockheed’s marquee projects were brought down in the budget-slashing crossfire.

As one Lockheed source told Robert Dreyfuss in 1996, Gingrich’s constant cheerleading actually started to wear on the company as the polarizing politician’s reputation soured: “We wanted to downplay any relationship between the speaker and Lockheed.” As Forbes later reported, having such a high-profile, reliable booster in Congress may have been bad the company’s health; it wasn’t until after Gingrich left the House that the company was able to restructure its operations and shore up its finances.

But it was a mutually beneficial relationship, for the most part. Gingrich made sure that Lockheed was in line for its usual fill of hefty defense contracts, and Lockheed made sure Gingrich always had support for his ventures, political and otherwise. The company donated the maximum $10,000 to Gingrich’s campaign in the lead-up to the 1994 Republican Revolution, and, just for good measure, shelled out another $10,000 in seed money for Gingrich’s weekly lecture series on American history, “Renewing American Civilization,” during which the Speaker dutifully talked up the company’s corporate virtues.

Perhaps the most brazen instance of Gingrich’s Lockheed-lobbying came in 1998. The Pentagon requested $59 million to build a C-130J transport plane. But when it passed through Gingrich’s committee, that figure morphed to $503 million—an 850-percent jump. As an Air Force spokesman put it at the time, “We didn’t request them. They just gave them to us.” But at least the C-130Js work. Gingrich was also a leading proponent of the F-22, the perpetual military fighter jet of the future (think Dipping Dots, if Dipping Dots were prone to mechanical malfunction and cost $320 million per serving.)

Oh, and about that NASA–Lockheed deal. When the space agency first floated a plan to commission reusable rockets in 1995, Gingrich was one of the leading supporters, suggesting that contractors could finish the project in a third of the time and less than half the cost it would take the government to do the job itself. Where did he get those figures? That’s just what the contractors told him, he explained.

Newt Gingrich certainly isn’t the only politician who’s guilty of double-talk when it comes to cutting the budget. But few politicians have talked louder for longer about slashing bureaucratic waste than Newt Gingrich.

“I’m a hawk, but I’m a cheap hawk,” he once explained. Well, except when he wasn’t.

*Correction: This post orginally stated that Lockheed’s headquarters was in Georgia.