Credit: Karsten Hartel via <a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cookiecutter_shark_head2.jpg">Wikimedia Commons</a>.

Ouch. All bite and no bark.

The first ever recorded instance of a human bitten by a cookie cutter shark is described in a paper now online in early view in Pacific Science.

An unfortunate human swimmer on a 47.5 kilometer/29.5 mile haul across the Alenuihaha Channel between the Hawaiian islands of Hawai‘i and Maui got nailed twice by this fearsomely ninjalike denizen of the deep, Isistius sp.

If you’ve spent any time at sea outside polar waters, chances are you’ve seen the toothwork of this gnarly little predator. It leaves deep round scars on whales, dolphins, tuna, billfishes, squids, and other larger marine life.

(Two cookie cutter shark bites in a pomfret. Credit: PIRO-NOAA Observer Program via Wikimedia Commons.)

As Kramer used to say: Nature, she is a mad scientist… and never more so than with the hunting technique devised by the cookie cutter shark. Here’s how FishBase describes it:

The cookie cutter shark has specialized suctorial lips and a strongly modified pharynx that allow it to attach to the sides of it prey. It then drives its saw-like lower dentition into the skin and flesh of its victim, twists about to cut out a conical plug of flesh, then pull free with the plug cradled by its scoop-like lower jaw and held by the hook-like upper teeth.

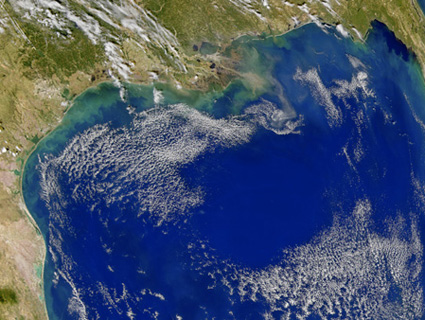

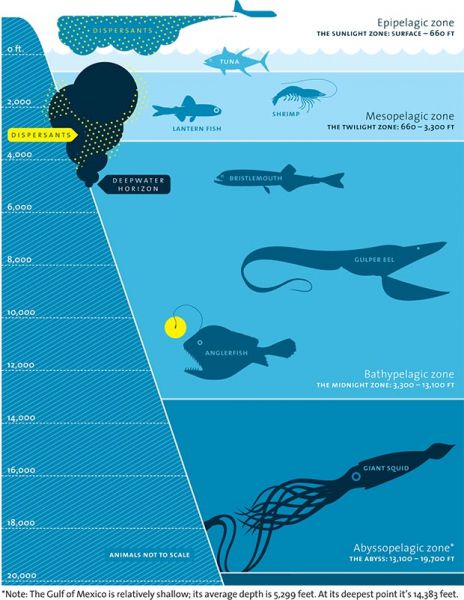

Cookie cutter sharks live in the mesopelagic zone and below and swim to the surface to feed at night. Credit: Nicholas Felton via Mother Jones.

Cookie cutter sharks live in the mesopelagic zone and below and swim to the surface to feed at night. Credit: Nicholas Felton via Mother Jones.

Cookie cutter sharks spend the daylight hours below the cusp of darkness—that is, below 1,000 meters/3,280 feet. They migrate to or near the surface at night, travelling 2,000-3,000 meters/6,560-9,840 feet on a diel cycle. That’s nearly two miles a day for a fish that maxes out at 56 centimeters/22 inches in length.

They ascend and descend alongside a massive community of marine life known as the deep scattering layer. (I wrote extensively about this community in my Gulf of Mexico oil piece in Mother Jones last year called The BP Cover-Up.)

(Scars on a dead Gray’s beaked whale, Mesoplodon grayi, possibly from cookiecutter shark bites. Credit: Avenue via Wikimedia Commons.)

But here the mad-scientist design gets even madder. The skins of cookie cutter sharks glow strongly bioluminescent—reported to radiate light for as long as three hours after death—part of their underwater camouflage wherein they hide among schools of glowing squid.

And no one likes squid better than many cetaceans. When whales and dolphins attack squid, cookie cutter sharks ambush the ambushers, darting out to steal a plug of flesh, then disappearing back into the bioluminescent background.

The human swimmer off Hawaii was attacked at night when the stern deck lights from the escort boat were lit and shortly after the escort kayak lit red and green bow lights. Here’s what the Pacific Science paper says:

About ten minutes after the kayak’s bow light was turned on, the victim was bumped by a squid. Over the next twenty minutes he was bumped by squid two or three more times in the shoulder and side areas at irregular intervals. At 2003 hrs, the victim suddenly felt a very sharp pain on his lower chest, and assumed it was a triggerfish bite. The sensation was instantaneous and localized, like a pin prick, and felt like a bite from a very small mouth. The victim yelped and swam over to the kayak, turned off the bow light, and was in the process of getting into the kayak with his legs vertical and “egg-beatering” to maintain position when he felt something bite his left calf. The time interval between the two bites was less than 15 seconds. The sensation of the bite to the leg was slightly more prolonged (but still very quick, less than a second), involved some pressure, and was less painful than the chest bite.

You can see images of these wounds at my blog Deep Blue Home. You can read the whole paper here.

Seems like FishBase will have to amend their listing for cookie cutter sharks. Currently it reads:

Not dangerous to people because of its small size and habitat preferences.

The Pacific Science paper concludes:

Humans entering pelagic waters at twilight and nighttime hours in areas of Isistius sp. occurrence should do so knowing that cookiecutter sharks are a potential danger, particularly during periods of strong moonlight, in areas of manmade illumination, or in the presence of bioluminescent organisms.