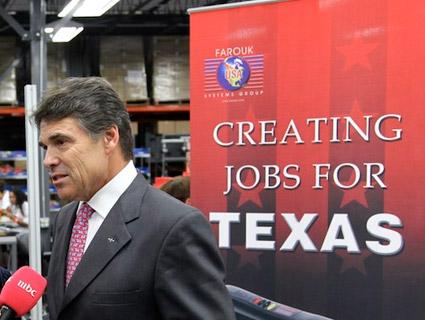

Perry speaks at a 2009 Texas Tea Party rally.<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/ritaquinn/3448611928/in/photostream/">Rita Quinn</a>/Flickr

The narrative was all ready to go: Texas Gov. Rick Perry’s 2010 re-reelection campaign was supposed to be an old-fashioned brawl between the incumbent governor of nine years and the state’s most popular politician, Republican Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison. Texas Monthly put the duo on its cover with the tag line, “It’s On and It’s Gonna Get Ugly.” Political junkies stocked up on popcorn.

But it didn’t turn out that way. After starting off 30 points down, Perry went on to crush Hutchison in the primary. The senator’s attacks on Perry mostly fell flat; instead, the sharpest critiques of the governor came from a third candidate: Debra Medina, a nurse and former Wharton County Republican Party chair, who, with zero name recognition or institutional support, a bare-bones budget, and a whole lot of tea party backing, soared to 20 percent support in the polls.

“I think Paul Burka at Texas Monthly said I’m the only person that’s ever been able to get to the right of Rick Perry—which is bizarre in my view because I don’t see him as a candidate of the right,” Medina says now. “He sells himself on the right, he packages himself on the right, but if you look at the record, he’s not conservative by any stretch.”

Medina’s bid ultimately fell short—owing in part to a disastrous interview on Glenn Beck’s radio program. But her tea party insurgency channeled a dissatisfaction felt by many Texas conservatives. It was hardly a blip, either; 61 percent of Texans voted against Perry in 2006 (he won in a four-way race), and when the University of Texas and the Texas Tribune polled the state this spring, just 4 percent said they’d like to see their governor run for president.

So what’s got them so upset? If you ask Medina, a longtime supporter of Rep. Ron Paul (R-Texas), it all starts with the budget. Perry has made austerity one of the centerpieces of his campaign. “In 2003, and again this year, my state faced billions of dollars in budget shortfalls,” Perry said in his campaign kickoff speech on Saturday in South Carolina. “But we worked hard, we made tough decisions, we balanced our budget—not by raising taxes, but by setting priorities and cutting government spending.”

But, much like former Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty, Perry hasn’t been the most disciplined conservative when it comes to cutting spending. When he faced a $27 billion budget deficit this spring—much of which was the product of a poorly crafted franchise tax he’d pushed through in the 2006 session—Perry and his allies closed the gap through a serious of budget tricks, deferring payments to future sessions and crafting deliberately rosy revenue projections. As Medina notes, when it comes to cutting spending, Perry’s predecessor, George W. Bush, actually had a better record. And rather than ax accessories (like tax incentives for the movie industry), Perry protected friendly business interests while taking funds out of essential services like education.

“Generally speaking, when you look at what he’s done, he’s a big-government, micromanage your family, micromanage your business ideologue,” says Medina, who briefly considered supporting a third-party candidate following her primary defeat. “My whole campaign could be summed up as: Gov. Perry is bashing Washington, but if you look at what he’s done, he’s managed Texas in much the same way.”

Moreover, while Perry has criticized President Obama for raising the debt ceiling, calling his approach “condescending” and suggesting that the nation was never at a risk of defaulting, the governor has quietly raised Texas’s own debt limit. Under Perry, the Lone Star State has borrowed more and more—going from $13 billion in debt when he took office in 2000, to $38 billion by 2008. “Gov. Perry has done exactly what the tea party is hollering at Washington, DC, right now: Don’t raise the debt limit,” Medina says. (As PolitiFact Texas noted, though, Texas’ debt total was well below the national average on a per-capita basis.)

But the tea party’s gripe with Perry extends beyond fiscal issues, to matters of individual liberty as well. Although he’s drawn cheers on the campaign trail with his pledge to make “DC as inconsequential in your life as I can,” he has not applied that same approach to Austin. Perry’s decision to make the HPV vaccine mandatory for adolescent girls (in an effort to reduce their risk of cervical cancer) elicited the ire of social conservative activists—and more recently, hits from right-wing bloggers like Michele Malkin.

And the governor sparked a mini-revolt within his party with his proposal for a Trans-Texas Corridor, a massive project that would, as its name suggests, build a toll road, rail lines, and telecommunication infrastructure across the length of the state. To clear the way for the project, the state would use eminent domain to confiscate land from rural Texans—playing into fears of big government and feeding conspiracy theories that the corridor was part of a looming “NAFTA Superhighway.” (Ultimately, the plan fell through.)

Meanwhile, as with his recent shift on the role of religion in public life (when asked in 2002 how it affected his politics he said “I don’t think it does, particularly“), Perry’s states’ rights crusading has also been a mostly recent development. He has talked up Texas’ right to secede and signed a resolution affirming the state’s sovereignty and 10th Amendment rights.

“The 10th Amendment was enacted by folks who remembered what it was have a very oppressive government, to be under the thumb of tyrants and an all-powerful government,” he said at a press conference last spring. “Unfortunately, the protections it guarantees have melted away over the years.”

But if that’s the case, Perry has been part of the problem, not the solution. As evidence, Medina cites Perry’s support for No Child Left Behind, the 2001 law that dramatically expanded the federal government’s role in education. While Utah opted out of the law entirely, and states like Minnesota (with a big push from a young state senator named Michele Bachmann) questioned the viability of the law, Perry opted not to block its implementation. To Medina, that makes his current tack, that “it’s a monstrous intrusion into our public affairs,” a bit hypocritical. Likewise, while Perry had harsh words for the American Recovery Reinvestment Act in 2009, he quietly collected almost all of the stimulus funds allocated to the state.

“There’s little to no evidence of the fact that he believes in state sovereignty and the 9th and 10th Amendments,” Medina says. “There’s been plenty of opportunities for him to exercise the state’s authorities, and he’s never done that.”

Not all of the tea party concerns outlined by Medina are likely to gain traction in the Republican primary. In particular, Perry’s cavalier approach to the state’s criminal justice system (allowing an innocent man, Cameron Todd Willingham, to be executed) has proven to be a nonstarter for his opponents. As one conservative focus group member told a Hutchison aide, “It takes balls to execute an innocent man.”

But on the economic front, the field has already devolved into a civil war. Before he dropped out of the race, Pawlenty was hit hard by Bachmann for his record in St. Paul, where he balanced budgets—like Perry—through deferred costs and accounting wizardry. Perry and front-runner Mitt Romney are already sparring on whose experience best matches the “real economy.” And with Bachmann making her anti-debt crusade a major part of her campaign, Perry’s Texas record could make him a natural target.

Much of the conservative criticism of Perry comes down to the fact that he’s a corporatist conservative less concerned about the 10th Amendment principles than he lets on. But then again: For the rest of the party, that’s kind of the appeal.