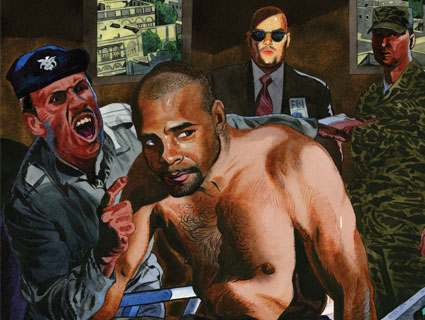

Michael Migliore, a 23-year-old American convert to Islam, was detained and questioned in England last week.Photo: Michael Migliore

Does the US government use British authorities to detain and question American citizens who don’t want to talk to FBI terrorism investigators without a lawyer present? A recent case suggests as much.

Last week, Michael Migliore, a 23-year-old American convert to Islam, was nearing the end of a trans-Atlantic cruise from New York to Southampton, England. From there, Migliore hoped to continue on to Italy, where he has family and holds dual citizenship. Migliore would have flown, but when he tried to, he discovered that he seemed to be on the US government’s no-fly list. He believes this was because he was a casual acquaintance of Mohamed Osman Mohamud, the accused “Christmas tree bomber.” He had to take a cruise ship across the Atlantic instead of flying.

As the Cunard liner neared Southampton harbor, Migliore, who was eating breakfast, noticed a speedboat set out from shore. According to Migliore, British authorities boarded, removed him from the ship, and detained and questioned him under British anti-terrorism law for 8 to 10 hours. He was told he had no choice but to cooperate. They confiscated his cell phone, iPod touch, a flash drive, and a book of Arabic grammar before sending him on his way.

Migliore told me in a phone interview from Italy on Wednesday that his British attorney says US officials were involved. He said that he and Mohamud had been “going to the same mosque pretty much” and that they had essentially lost touch around 18 months before Mohamud’s arrest in November 2010. (Mother Jones intern Hamed Aleaziz recently wrote about attending Mohamud’s mosque as a child in Oregon.) As Trevor Aaronson reported in the September/October issue of Mother Jones, Mohamud’s arrest was part of an extensive FBI sting operation targeted at a young man who “barely had the capacity to put his shoes on in the morning,” according to one of Aaronson’s law enforcement sources.

In the wake of the Christmas tree bombing arrest, the FBI came to talk to Migliore. He says the agents who visited him at his home near Portland, Oregon, shortly after Mohamud’s arrest “weren’t very happy and started raising their voices” when he told them he’d like to set up an appointment to talk with them with his lawyer present. Gadeir Abbas, Migliore’s American lawyer, said the FBI didn’t follow up with his client after the initial meeting and that Migliore had no prior criminal record.

“I didn’t do anything wrong, so I don’t understand why I’m going through all this,” Migliore says. “I don’t know what makes them think that I’m some kind of terrorist who wants to commit some sort of criminal act. This is really incredible what’s going on. I can’t believe I had to take a 12-day trip to get back home. I didn’t do anything. What the heck is the point?”

Migliore’s case hasn’t drawn much attention—though the Associated Press covered the story last week, its report gained little traction in the media. But the 23-year-old’s story has great significance for young American Muslims who plan to travel abroad. As I reported in a separate piece in the September/October issue, the FBI’s counterterrorism cooperation with foreign governments sometimes leads to the detention of Americans abroad. In other words, the US government sometimes gets other countries to arrest, detain, and interrogate American terrorist suspects on its behalf.

As with many of these cases, there is no evidence that British authorities detained and interrogated Migliore at the behest of the United States. But Migliore says his British lawyer told him that was in fact what happened, and given the FBI’s demonstrated interest in the young man and his apparent no-fly status, it wouldn’t be surprising. (As of publication time, the Justice Department has not provided comment.)

If the United States was indeed involved in getting the British to interrogate Migliore, this appears to be another case of the US government using its allies to sidestep constitutional restrictions that protect US citizens here in the States. The British authorities did eventually provide a British lawyer, but Migliore was told that under British anti-terrorism law, he had no right to remain silent, and if he refused to answer any question he could be arrested. In this particular case, Migliore doesn’t claim he was mistreated—just pulled off his boat before reaching shore, humiliated, and interrogated for hours without his American lawyer.

Some other US allies involved in this type of scenario reportedly have been far harsher. Several Americans—most of whom have never been charged with crimes—claim to have been abused by foreign governments at the behest of or even with the cooperation of the United States. Civil libertarians call this process “proxy detention” or “rendition-lite.”

After I spoke with FBI sources for the above report who admitted that the US government does in some cases advise foreign governments to detain Americans, it became clear that Muslim Americans, particularly young men, faced a sobering reality: If you don’t want to be detained and questioned abroad, it’s probably best not to go there—especially to places like Somalia or Yemen that might raise red flags among US officials. In light of the Migliore case, the equation appears to have broadened: If you believe the US government suspects you of terrorism, and you don’t want to talk to the authorities without the benefit of your full constitutional rights, don’t leave the country at all.