<a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/yourdon/3979323453/sizes/m/in/photostream/">Ed Yourdon</a>/Flickr

Twitter is great for staying up-to-date on, well, pretty much everything: the news, celebrity gossip, your roommate’s best-friend’s breakfast. But a new paper out today in the journal Science suggests that Twitter can also be used to track peoples’ moods. The researchers found that, across the globe, tweets are predictably upbeat or cranky based on the local time of day.

Cornell University sociologists Scott Golder and Michael Macy spent two years collecting 509 million tweets from 2.4 million users in 84 different countries (albeit with a notable dearth of representation from Africa). Using a well-established text analysis tool, they scored tweets based on their use of hundreds of positive words (like “happy” or “enthusiastic”) or negative words (like “sad” or “anxious”). When Macy and Golder plotted these scores against the tweet’s time stamp, they found what should come as no surprise to anyone who works a nine-to-five: peoples’ moods are best early in the morning, slowly deteriorate as the day wears on, then finally pick up in the evening (read: after happy hour). And, cultural differences be damned, the same was true worldwide, suggesting mood is hard-wired in the human psyche.

“Twitter is a goldmine for being able to observe human behavior,” Macy said. “We all have basically the same biology, and the pattern we found was very robust.”

Macy and Golder aren’t the first to tap Twitter’s 200 million users for research; linguists, gender theorists, political analysts, and others have studied what how great the impact of 140 characters can be. Even The New York Times used Twitter as a database for their coverage of the 2010 elections. Similar research on mood last year from Northeastern University yielded the trippy time-lapse video below. But today’s paper is one of the first to examine tweets on a global, cross-cultural scale.

The pair used the programming software Twitter makes available to app developers to amass the huge database of tweets, which they originally intended to use to shed light on peoples’ daily activity schedules. But it quickly became apparent, Macy said, that the data supported what sociologists already guessed about how mood changes throughout the day. The fact that people get irritable during the work day was no surprise, he said: “Well, of course. Work sucks.”

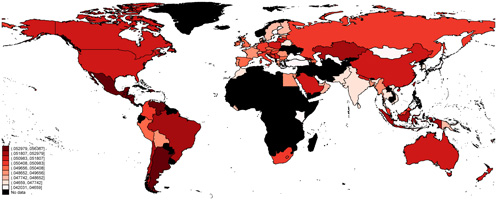

Who’s happiest? This map shows the average level of positive feelings in each country over a year; darker red means more positive (black means no data was available).

Who’s happiest? This map shows the average level of positive feelings in each country over a year; darker red means more positive (black means no data was available).

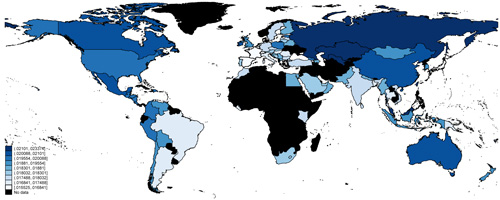

Who’s saddest? This map shows the average level of negative feelings in each country over a year; darker blue means more negative (black means no data was available). Images © Science/AAAS

Who’s saddest? This map shows the average level of negative feelings in each country over a year; darker blue means more negative (black means no data was available). Images © Science/AAAS

What was surprising, however, was that the daily mood fluctuation was roughly the same on weekends, although people seemed in better moods overall. Moreover, the morning peak in positive tweets hit about two hours later on weekends, which Macy attributed to people sleeping in. This “weekend effect” was even confirmed in the United Arab Emirates, where the workweek runs from Sunday to Thursday. In general the consistency was so great, he said, that it suggests mood is based more on biological rhythms than on culture. While this hypothesis isn’t new, this is the first study to use real-time, unprompted textual data from individuals to support it. The same study could be done using Facebook status updates or other social media tools, Macy added, but the Twitter data was the most readily accessible.

The next step, Macy said, will be to examine what individual people are tweeting about to deduce demographic information about them. Knowing a tweeter’s age, gender, occupation, or ethnicity could shed more light on where our finicky moods come from. “[Our study] is an example of the type of research that’s now possible, that you simply couldn’t do in the past. We can observe human behavior in real time.”