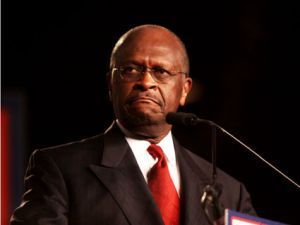

Herman Cain in PhoenixJack Kurtz/ZUMA Press

Since the news first broke last month that GOP presidential candidate Herman Cain had been the subject of at least two sexual harassment complaints while he was working at the National Restaurant Association, the right-wing establishment has come swinging to his defense. They’ve called Cain’s accusers humorless kvetchers who overreacted to Cain’s harmless if gregarious behavior. They’ve suggested that sexual harassment doesn’t exist. Rush Limbaugh even said that if women wanted to be left alone, they should don burkas.

But all of this chatter about whether women take sexual bawdiness too seriously obscures a critical point about the nature of sexual harassment: It’s not about sex. It’s about power.

The original Politico story about Cain’s past made clear that if the allegations were true, Cain wasn’t just some rich horny guy looking to get laid or a charismatic extrovert with a misunderstood sense of humor. He was someone who had seriously abused his authority, a much more serious problem for someone seeking the nation’s highest office.

If he were simply randy, Cain could have found casual, extramarital sex anywhere, and not just from the prostitutes who, in the mid-1990s, were a regular feature on the DC streets just a few blocks from the National Restaurant Association. But if the allegations are true, what Cain was doing was something different. He was allegedly showering subordinates and an unemployed job-seeker with unwelcome sexual advances that they weren’t in a very good position to decline. (It’s notable that none of the women who have complained about Cain seem to have outranked him.)

Being harassed at work by a boss or other superior is not the same thing as being on the receiving end of catcalls by construction workers or getting groped in a bar, however unpleasant those things may be. Sexual harassment is illegal because it’s a form of discrimination, a way of preventing women from advancing in the workplace. If you don’t believe me, just look at what happened to the women Cain allegedly harassed. Sure, they may have gotten some small settlements, but they also had to leave their jobs. Cain, on the other hand, got to stick around, at least for a while, and he has thrived professionally ever since.

If you’re a woman, getting sexually harassed at work can ruin your life. When someone in a position like Cain’s suggests to a woman looking for a job that the price of his help is a blow job, he’s coercing her in a way no drunk bar fly could ever hope to. And she has no good exit. Report the guy and she will forever be branded as a complainer, a career killer if there ever was one. Refuse the sex, the implication goes, and there’s no telling what the guy will do to her career out of spite. And the blow job itself, of course, is out of the question (unless the woman is truly desperate, which happens). It’s a humiliating and demoralizing situation to be in. Most women who’ve been there just try to muddle through with as little damage as possible. The few who don’t pay a high price for their bravery.

That the media have taken the sexual misconduct allegations against Cain as seriously as they have is progress, even if some of the reaction to the Politico story hasn’t been a model of enlightenment. Florence Graves, the woman who broke the story about former Sen. Bob Packwood’s history as a serial harasser, had trouble finding a publisher for her exposé in 1992. She wrote recently about the experience of investigating the Republican from Oregon:

Some media brass still considered it a story “about sex,” about Packwood’s private life, instead of about abuse of power that involved sexual misconduct rather than financial or some other misconduct traditionally deemed relevant to the public interest.

But Graves persevered, and eventually the Washington Post ran her story, but only after Packwood had been reelected. (The paper didn’t want to be accused of seeking to interfere in an election, and so it sat on the story until after voters sent Packwood back to the Senate for another term.) Later, Congress held hearings in which 17 of the 40 women Graves identified testified about their experiences being harassed by Packwood.

Graves notes: “Even though the media often downplayed—sometimes even trivialized—the profound consequences Packwood’s behavior caused many of his victims, I knew there were serious repercussions for several women who not only had been humiliated, scared or degraded, but also professionally or financially ruined. Some quit their jobs—uprooting their families or taking lower-paying work—because of Packwood’s persistent unwelcomed advances.” In 1995, Packwood was forced to resign.

A few years later, I was sitting in meetings at the Washington Post’s investigative unit, where I was working at the time, when the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke during the Clinton administration. There were heated debates among editors and reporters as to whether the story about the White House intern deserved a serious examination. After all, plenty of presidents had been womanizers who engaged in extramarital affairs. But ultimately, my editor, Rick Atkinson, overruled any objections, saying, “It’s not about sex. It’s about abuse of power.” Clinton was nearly impeached as a result of his behavior, and it wasn’t just because he had a little recreational sex.

In the Cain scandal, those lessons seem to have been forgotten, as the power issues at the root of the allegations have largely been obscured by the focus on sex. But ultimately, voters are not going to have to decide whether to elect a boor. They’re going to have to consider whether they want a president who may delight in using his power to manipulate, degrade, and ultimately repress people below him, just because he can.