<a href="http://www.twistedmusic.com/galleries/category/369/">Twisted Music</a>

Shpongle—a motly ensemble led by flute-playing senior citizen Raja Ram and Simon Posford, a DJ who travels the world sampling exotic music—occupies a strange place in the already out-there realm of electronic music. And while you may never have heard of them, they’ve been touring the world for two decades now, and boast millions of views on YouTube.

Though fans identify Shpongle as psychedelic trance, Ram and Posford insist their globally influenced sound cannot be categorized. Sure, plenty of musicians make that claim, but Shpongle’s performance at Oakland’s Fox Theater on Halloween weekend convinced me that “unclassifiable” is a pretty apt characterization of their audiovisual freakshow.

Most electronic acts merely have a DJ, a mixer, and some turntables. Shpongle is a multi-instrumental, multi-sensory spectacle—an eight-piece band accompanied by neon-costumed singers, samba dancers, horned monsters on stilts, and a human slinky. Yeah, you heard me right. Watch:

Onstage, Shpongle is an amalgamation of world music, psychedelic visuals, and downbeat trance tempos. At one point, Ram, clad in neon-robes, played his flute as he chased a giant horned monster around the stage—even as the aforementioned slinky contorted nearby.

Posford orchestrates the drums, cello, guitar, flute, bass, violin, and vocalists, while mixing in electronic beats and his found sounds to create strange yet beautiful songs. And when one of their songs announced, “Let’s get Shpongled”—which to fans is a synonym for “stoned,” the crowd—many of whom donned their best monster, fairy, and mythical-creature attire for the occasion—went wild.

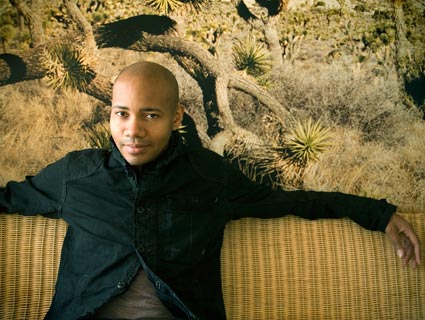

At Berkeley’s Claremont Hotel the next day, I sat down with a recuperating Ram and Posford to talk about their bizarre musical circus, their search for unique sounds, and the origin of their somewhat unusual name.

Mother Jones: First things first. What on Earth does Shpongle mean?

Simon Posford: It was a word made up by Raj. We were at Glastonbury [music festival], and he’d taken something that might not have been alcohol, and he said, “I’m feeling really Shpongled.” All these words came out at once—stoned, mongled, gongle—they sort of fell out of his mouth in the form of one word. I said, “Let’s use that as our banner.” We’d only made trance before, but we wanted to do something different.

MJ: Dubstep is going mainstream. Do you think trance is ever going to appeal to a broader audience?

Raja Ram: No. I’ve got a record company, as Si does, so I’m very aware on a practical level that it’s pretty well dead. Electronic music has moved into hundreds of other genres, and dubstep is one of them. But just like everything else, dubstep will pass. House will probably go on forever—house is like a cockroach; you can’t kill it, even with a nuclear bomb. [Laughs.] But I like house. I’m not putting it down.

SP: The problem with trance is it hasn’t adapted. So in the ’90s, when psychedelic trance arrived, it was a very new genre and it was very exciting, whereas house music was very stagnant. Now it’s the opposite—psychedelic trance really all sounds the same, while house music has evolved.

MJ: Do you think your music sounds like the rest of psychedelic trance?

SP: No. I wouldn’t even call it psychedelic trance; I hate it when people call it that.

RR: No one’s ever managed to reproduce Shpongle. We have a lot of imitators, but even if they catch up to us, by the time we bring out the next album, they can’t because we’ve got so many new ideas and new technology. And we’ve just started.

MJ: So what is Shpongle?

SP: We have so many different influences, you can’t really put us in one pigeon hole.

RR: I would say that Shpongle is a drug that’s administered through the ears.

MJ: With positive side effects?

RR: Oh absolutely. Completely legal, beneficial, and mind-enhancing. Music is everything; without it, we’re nothing. We’re just living vibrations of molecular tinglings, and without music we’d explode into nothing and go down a quantum hole.

MJ: You have a ton of global influences. Where do they come from?

SP: On the last album, Ineffable Mysteries From Shpongleland, we had quite a lot of Indian influence. I went to India with a little handheld recorder and we went round in a rickshaw and I asked the driver, “Where can we find some musicians?” He took us to his cousin’s music shop, and they were pulling down all these exotic instruments off the walls and playing them. This one guy was playing a sarod, which is a stringed instrument, and he made it sound like he was strangling a cat—it really sounded awful. But he explained he was actually a singer, so I said, “Even better; let’s hear it.” When he started singing, it was so good I had to record him properly. So we invited him back to the hotel, and he brought another female singer with him. We put headphones on them and made them a beat, and they just sang along. Then I took it home and edited it into the performance.

MJ: So you travel the world hunting for sounds.

RR: Yes, we’re always on the hunt.

MJ: Where do you plan to look next?

RR: At Simon’s place, I was in the garden, cracking bamboo and plants, walking on gravel, scraping the barbeque, spinning a coin on the table, dropping marbles on the floor—there’s just a million sounds—and when Si gets them, he can manipulate them and process them so they sound very different. It’s an original sound to start with, so you’re going to end with something very shpongle-y.

MJ: Who puts together the visual aspects of your show?

SP: Mainly Raj. When we’re in the studio, and I’m working on the computer, Raj gets on the internet…

RR: Who would amuse the crowd? Can we get that midget juggler nude? [Laughs.]

MJ: Yeah, at your show last night, I felt like I was witnessing a circus.

RR: Well I’m the elephant, and he’s the trainer.

MJ: With such an over-the-top live show, what’s it like in the studio?

SP: Our only rule in the studio is that we have no rules. We don’t go in and try to make a trance record or an ambient record. We literally just have fun.

RR: Yeah, we don’t want to repeat formulas, and that’s a very important thing; if you’re on to something but you start repeating it, that’s the end of your career. I think the whole of music comes down to one’s personality. It’s not about the notes or how you press the keys; it’s where you are in your evolution of consciousness.

SP: The KLF said in a book that two artists can make a track using just the same kick drum, the same tempo—nothing else—and one record would be undoubtedly better than the other because the soul of the artist always shines through.*

MJ: If the personality and soul of an artist is so important, how would you describe each other’s personalities?

SP: Raj sits there and writes in these books while I’m on the computer working on the music, and he’ll do a thousand drawings. Once I was flipping through one of the books and saw that he’d written, “Simon is my father and my son.” For me, it’s sort of the same. I really feel Raj is my guru and my student. Even though he may deny it, Raj is a very spiritual person and a very accomplished musician, and I’ve learned so much about art and music from him. In the studio, he’s my muse when we’re making the music. He has this wealth of 70 years of an inquiring mind to draw upon. He’ll tell me stories and that will somehow translate into the sound of the music.

RR: We have this strange chemistry. It’s sort of like the Coca-Cola formula. One wouldn’t work on its own, but when you take the two mystic ingredients, you come up with the magic potion, the magic Shpongle.

MJ: And Raj, how would you describe the soul of Simon the artist?

RR: Well he’s just an incredible friend, and someone I’ve learned an amazing amount from. He is a complete musician and I’m mystified how he does it. It’s amazing to know someone like him. Wherever we go, in restaurants or in the street, people come up and say how they’ve been influenced, how they’ve become musicians. And that’s the highest praise.

Click here for more music features from Mother Jones.

Correction: An earlier version of this story mistakenly quoted Simon as saying, “A caliph said in a book that two artists can make a track using just the same kick drum, the same tempo—nothing else—and one record would be undoubtedly better than the other.” He actually said, “The KLF said in a book that two artists can make a track using just the same kick drum, the same tempo—nothing else—and one record would be undoubtedly better than the other.” The sentence has been corrected.