Zhang Jun/Xinhua/ZUMA Press

If the congressional supercommittee fails this week to agree on a plan to reduce the federal budget deficit by $1.2 trillion or so over the next decade, it won’t be for lack of advice from Washington players and policy wonks.

For years, deficit hawks and policy advocates in the nation’s capital have been fighting over what to do about the US government’s budget and long-term fiscal challenges. And their weapon of choice often is…the chart. As these policy warriors have circled around the supercommittee—sometimes testifying before it—they have brandished various graphics to make their point in ways far more dramatic than lectures on baseline projections and budget authority.

The supercommittee, created as part of the debt ceiling agreement crafted in August, is comprised of six members from each party. They’ve been on an extraordinarily tight deadline to come up with a plan, due Wednesday, that will pass muster with their colleagues—or else a series of automatic spending cuts will take place starting in 2013. Here’s a brief guide to the supercommittee’s super-tough job via the charts.

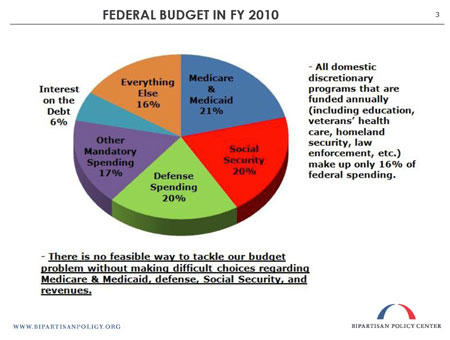

Why the supercommittee won’t fix the problem: Earlier this month, the supercommittee solicited advice at a hearing from Clinton-era Office of Management and Budget director Alice Rivlin and the co-chairs of President Obama’s debt commission, Erskine Bowles and former Wyoming Sen. Alan Simpson. They addressed all the things that the supercommittee is essentially banned from touching: entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare—even though, as Rivlin pointed out, escalating health care costs related to an aging society are the primary driver of long-term debt. Rivlin’s chart:

FY 2010 Federal Budget

FY 2010 Federal Budget

If closing down the Pentagon won’t make a dent, this certainly isn’t going to help much: Members of Congress have been frantically lobbying their colleagues on the supercommittee to spare this or cut that. The House committee on science, space, and technology, for example, wrote to the committee proposing “over $1.5 billion in savings in FY12 alone.” Most of the cuts fall heavily on environmentally friendly programs like energy efficiency, renewable energy research and incentives, or anything having to do with climate change. Meanwhile, the committee pleaded for the Department of Energy’s Office of Fossil Energy to be spared any cuts. The proposed savings are barely 1 percent of what’s needed to meet the committee’s goals.

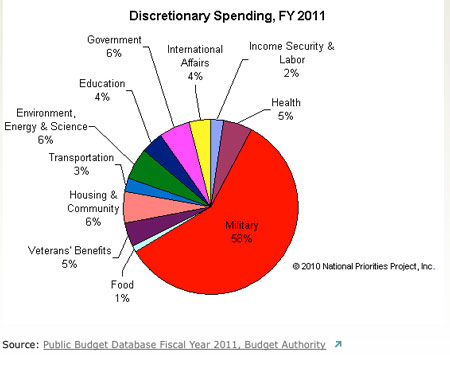

Meanwhile, the House armed services committee implored the supercommittee “to refrain from any further cuts in National Defense,” arguing that “not all elements of the federal budget are equal,” and that defense had already experienced “significant reductions” since the debt-reduction discussions began. One glance at this pie chart, though, and it’s clear why defense is an obvious target.

Discretionary Spending FY 2011, National Priorities ProjectEven killing off the Pentagon, though, won’t solve the budget problem. CBO director Doug Elmendorf told the supercommittee that eliminating all discretionary spending, including the Pentagon, still won’t make a dent in the national debt any time soon. (See the first chart.)

Discretionary Spending FY 2011, National Priorities ProjectEven killing off the Pentagon, though, won’t solve the budget problem. CBO director Doug Elmendorf told the supercommittee that eliminating all discretionary spending, including the Pentagon, still won’t make a dent in the national debt any time soon. (See the first chart.)

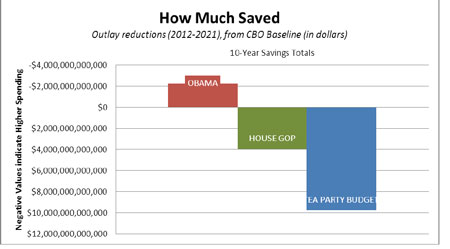

No, the tea party’s plan won’t work either: Last week, congressional Republicans tried to hold a joint “hearing” on a proposal from the Tea Party Debt Commission (PDF), which was convened by FreedomWorks, the advocacy group run by former Republican House Majority Leader Dick Armey. The group held “field hearings” around the country, a disproportionate number of them (5 of 12) in Utah.

The tea partiers who helped crowd-source the budget proposal see no need for good chunks of the federal budget. They’ve proposed eliminating the departments of energy, education, commerce, and housing and urban development; doing away with farm subsidies, student loans, and “foreign aid to countries that don’t support us”—all while preserving the Bush tax cuts for the wealthy.

Naturally, the tea partiers believe their “bold” but “feasible” plan will result in significant savings: FreedomWorksWhile the tea partiers are mortally opposed to any tax increases, they do propose some revenue enhancements, like selling off “a portion” of the gold in Ft. Knox ($190 billion) and unused land and mineral rights in the West.

FreedomWorksWhile the tea partiers are mortally opposed to any tax increases, they do propose some revenue enhancements, like selling off “a portion” of the gold in Ft. Knox ($190 billion) and unused land and mineral rights in the West.

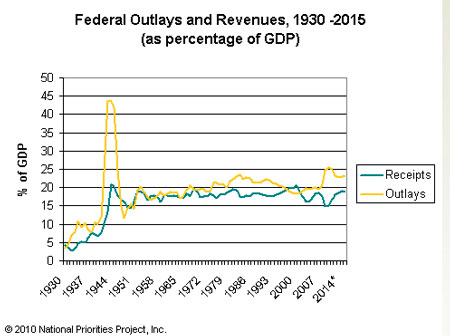

While not specifically budget-savings items, the tea partiers helpfully ask the supercommittee to “ensure sound money,” by letting Americans “transact business in US minted precious-metal coins and US issued gold-backed notes.” All together, the proposal claims that the tea party plan would balance the budget in four years and shrink the federal government from 24 percent of GDP to 16 percent, a level that hasn’t been seen in more than six decades.

National Priorities ProjectPerhaps its not surprising that the congressional “hearing” on the proposal, convened by Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) on Thursday afternoon, was disbanded before it even started because, well, it wasn’t really a hearing. (No Democrats were involved.) The tea partiers had to decamp to hold their discussions elsewhere.

National Priorities ProjectPerhaps its not surprising that the congressional “hearing” on the proposal, convened by Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) on Thursday afternoon, was disbanded before it even started because, well, it wasn’t really a hearing. (No Democrats were involved.) The tea partiers had to decamp to hold their discussions elsewhere.

The eviction didn’t bode well for any of their proposals actually becoming law. If the supercommittee members can’t even agree to modest changes in the tax code, it’s hard to see a consensus forming over returning to the gold standard.

The case for doing nothing: If the supercommittee fails, it may not be such a bad thing. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities calculated that under current law, simply doing nothing—not extending the Bush tax cuts, not postponing cuts to Medicare reimbursements for doctors, and allowing the automatic spending cuts to take place—would shave more than $7 trillion off the deficit in the next decade, seven times more than the committee is fighting over now. Thankfully, there’s a chart about that too: