Newt Gingrich is back with a vengeance. In the last two weeks, he’s taken credit for the success of Mitt Romney’s venture capital firm (and the entire economic boom of the 1990s), the fall of the Soviet Union, and the demise of the “welfare state.” The former speaker of the House has hit the stump in Iowa and Florida with a level of confidence befitting a man whose outsized cranium forced his high school football team to order a custom-made helmet.

Although his presidential bid crashed rather spectacularly in the beginning, Gingrich seems to have since found his mojo; in the eyes of MoJo, though, he never really went away. Since the early 1980s, when it “scooped the world on Newt Gingrich” (as his first wife later put it), the magazine has devoted gallons of ink and tens of thousands of words to exploring the ideas, emotions, and (if we must be honest) dental work of the architect of the Republican Revolution. Here’s a quick tour through the highlights:

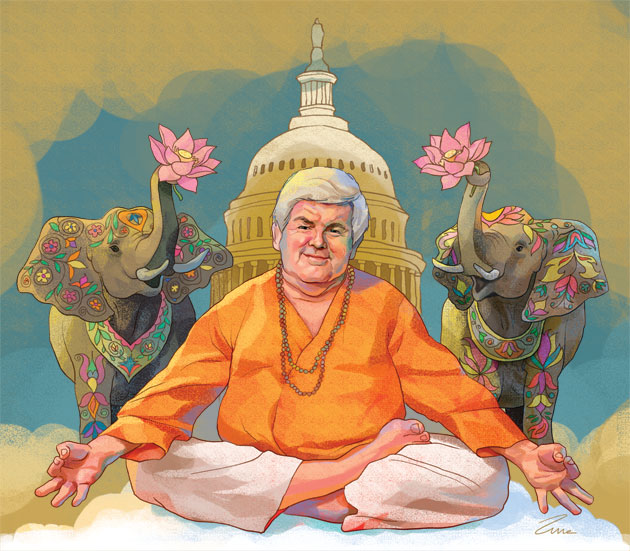

Illustration: Rudy VanderlansGingrich was just beginning to make a name for himself in 1984 when MoJo sent David Osborne down to Georgia to find out more. What struck Osborne was the widespread alienation felt by those who had long known Gingrich. One former aide called him “dangerous” and “amoral.” The Gingrich who had accepted a teaching position at West Georgia College 14 years earlier was a thing of the past:

Illustration: Rudy VanderlansGingrich was just beginning to make a name for himself in 1984 when MoJo sent David Osborne down to Georgia to find out more. What struck Osborne was the widespread alienation felt by those who had long known Gingrich. One former aide called him “dangerous” and “amoral.” The Gingrich who had accepted a teaching position at West Georgia College 14 years earlier was a thing of the past:

At the time, remembers Lee Howell, then editor of the student newspaper, Gingrich had “moddish” long hair and the tolerant cultural views of a young professor. He would come down to the newspaper office to talk and have a beer (though liquor was not allowed there), or have students over to his house for long philosophical discussions. He didn’t mind if people drank, others remember, or even smoked a little dope. One of his friends lived with a girlfriend, and Gingrich provided emotional support for another couple going though an abortion. To people on campus, Gingrich was a young liberal.

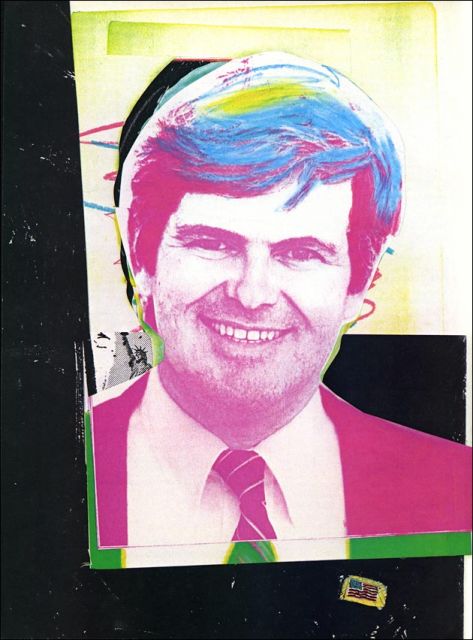

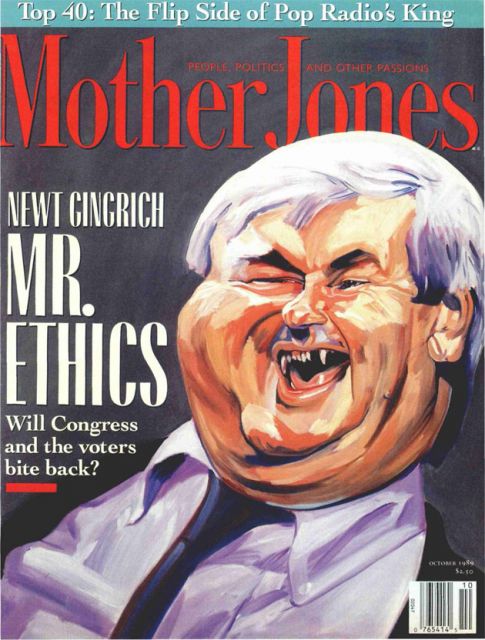

Cover of the October 1989 issue. Illustration: Philip Burke

Cover of the October 1989 issue. Illustration: Philip Burke

Five years after Mother Jones helped introduce Gingrich to the world, the magazine’s David Beers returned to Georgia to examine a politician who had changed considerably since his early days in the House. In 1984, “Gingrich was hard to take seriously,” Beers wrote. By October 1989, you ignored him at your peril. According to Dolores Adamson, a former aide, Gingrich had begun requiring a staffer to record his every utterance, to be preserved in his future public archives: “If posterity was slighted because a staffer failed to record him, Gingrich would dock that person’s pay up to $200—and dock Adamson’s as well. Then, for good measure, ‘He’d cut you down, blast you unmercifully.'”

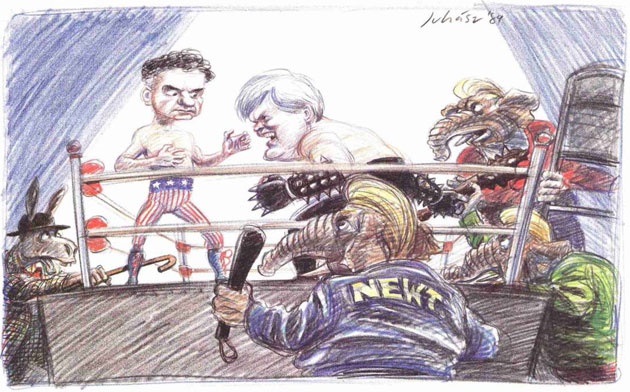

Illustration: Victor JuhaszJust a few months earlier, Gingrich had forced Speaker of the House Jim Wright (D-Texas) to resign over ethics violations. But when Beers suggested that Gingrich’s own lecture circuit paychecks might raise conflict-of-interest issues, the Georgian scoffed: “The idea that a congressman would be tainted by accepting money from private industry or private sources is essentially a socialist argument.”

Illustration: Victor JuhaszJust a few months earlier, Gingrich had forced Speaker of the House Jim Wright (D-Texas) to resign over ethics violations. But when Beers suggested that Gingrich’s own lecture circuit paychecks might raise conflict-of-interest issues, the Georgian scoffed: “The idea that a congressman would be tainted by accepting money from private industry or private sources is essentially a socialist argument.”

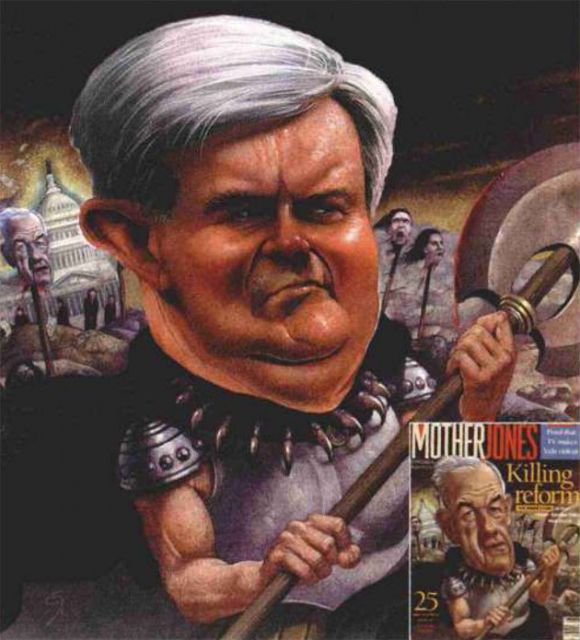

Illustration: CF PayneBy 1995, the newly ascendant speaker of the House had emerged as one of the most powerful congressman of the last century—and one of the most radical. “Newt Gingrich is the most dangerous man in America today,” wrote MoJo editor Jeffery Klein. “For more than 20 years, Newt has commanded a war to seize the speakership—only recently have troops and lieutenants joined his campaign. Newt isn’t merely a creature of the moment, Rush Limbaugh’s dittoheads hooked up with the legislative arms of the religious right.” Gingrich, Klein argued, was the movement.

Illustration: CF PayneBy 1995, the newly ascendant speaker of the House had emerged as one of the most powerful congressman of the last century—and one of the most radical. “Newt Gingrich is the most dangerous man in America today,” wrote MoJo editor Jeffery Klein. “For more than 20 years, Newt has commanded a war to seize the speakership—only recently have troops and lieutenants joined his campaign. Newt isn’t merely a creature of the moment, Rush Limbaugh’s dittoheads hooked up with the legislative arms of the religious right.” Gingrich, Klein argued, was the movement.

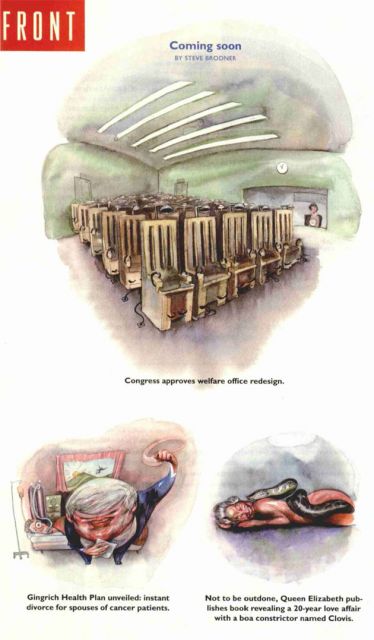

Illustration: Steve BrodnerGingrich had built his reputation by tackling corruption—but there was something of a double standard. Newt “called Clinton the ‘enemy of normal Americans,’ and threatened to shut down the presidency with a slew of ethics investigations. Oh, but [he] wants to abolish the House Ethics Committee.”

Illustration: Steve BrodnerGingrich had built his reputation by tackling corruption—but there was something of a double standard. Newt “called Clinton the ‘enemy of normal Americans,’ and threatened to shut down the presidency with a slew of ethics investigations. Oh, but [he] wants to abolish the House Ethics Committee.”

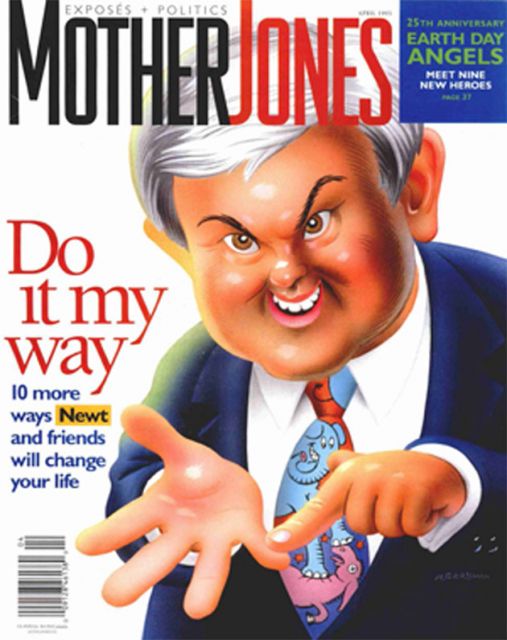

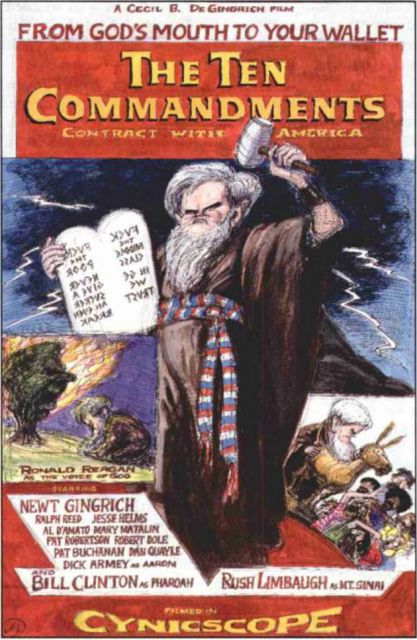

Cover of the March/April 1995 Issue. Illustration: Robert GrossmanGingrich’s Contract with America was just a first-step in a plan to revolutionize American government. The corrupt welfare state was on its way out, and in its place was something new and not entirely comforting. In his 1995 piece, “10 Ways the Republicans Will Change Your Life,” Richard Blow zeroed in on the fate of the Food and Drug Administration: “Gingrich has actually called for replacing the FDA with a ‘council of entrepreneurs,’ claiming that the market will take care of any poisonous foods or drugs after the fact through legal actions. In other words, if your child is born deformed by a drug such as thalidomide—the drug that prompted the FDA to require safety testing—you can sue, and future companies will pay attention.” Except that the Contract with America also pledged to make it significantly more difficult to file lawsuits.

Cover of the March/April 1995 Issue. Illustration: Robert GrossmanGingrich’s Contract with America was just a first-step in a plan to revolutionize American government. The corrupt welfare state was on its way out, and in its place was something new and not entirely comforting. In his 1995 piece, “10 Ways the Republicans Will Change Your Life,” Richard Blow zeroed in on the fate of the Food and Drug Administration: “Gingrich has actually called for replacing the FDA with a ‘council of entrepreneurs,’ claiming that the market will take care of any poisonous foods or drugs after the fact through legal actions. In other words, if your child is born deformed by a drug such as thalidomide—the drug that prompted the FDA to require safety testing—you can sue, and future companies will pay attention.” Except that the Contract with America also pledged to make it significantly more difficult to file lawsuits. Illustration: Steve BrodnerIn Gingrich lore, there are few episodes more infamous than the story of the young congressman showing up at the hospital to discuss the terms of divorce with his first wife—as she was recovering from surgery to remove a cancerous tumor. Reflecting on his first divorce in 1984, Gingrich told our David Osborne: “I guess I look back on it a little bit like somebody who’s in Alcoholics Anonymous—it was a very, very bad period of my life, and it had been getting steadily worse…I ultimately wound up at a point where probably suicide or going insane or divorce were the last three options.”

Illustration: Steve BrodnerIn Gingrich lore, there are few episodes more infamous than the story of the young congressman showing up at the hospital to discuss the terms of divorce with his first wife—as she was recovering from surgery to remove a cancerous tumor. Reflecting on his first divorce in 1984, Gingrich told our David Osborne: “I guess I look back on it a little bit like somebody who’s in Alcoholics Anonymous—it was a very, very bad period of my life, and it had been getting steadily worse…I ultimately wound up at a point where probably suicide or going insane or divorce were the last three options.”

Illustration: Victor JuhaszIf all went according to plan, 1994 was to be only the beginning of a new era of Republican leadership. “The contract is a political document for 1996,” one top GOP aide told Major Garrett the next year, referring to Gingrich’s famous campaign pledge. “It was never meant to be a governing document. We don’t care if the Senate passes any of the items in the contract. It would be preferable, but it’s not necessary.”

Illustration: Victor JuhaszIf all went according to plan, 1994 was to be only the beginning of a new era of Republican leadership. “The contract is a political document for 1996,” one top GOP aide told Major Garrett the next year, referring to Gingrich’s famous campaign pledge. “It was never meant to be a governing document. We don’t care if the Senate passes any of the items in the contract. It would be preferable, but it’s not necessary.”

Illustration: Victor JuhaszThe Contract for America was custom-made to give Republicans a foot in the door. As Garrett reported, “GOP pollster Frank Luntz, who also polled for Patrick Buchanan’s presidential campaign and later for Ross Perot’s, tested the components of the contract before focus groups. Only those provisions that scored a favorability rating of 60 percent or higher made it into the contract.” Luntz, in an interview with Garrett, was candid: “I’m a pollster. I don’t worry about policy. I know what the people want, and I think it’s time the Republican Party starts giving people what they want…”

Illustration: Victor JuhaszThe Contract for America was custom-made to give Republicans a foot in the door. As Garrett reported, “GOP pollster Frank Luntz, who also polled for Patrick Buchanan’s presidential campaign and later for Ross Perot’s, tested the components of the contract before focus groups. Only those provisions that scored a favorability rating of 60 percent or higher made it into the contract.” Luntz, in an interview with Garrett, was candid: “I’m a pollster. I don’t worry about policy. I know what the people want, and I think it’s time the Republican Party starts giving people what they want…”

Illustration: Victor JuhaszThe Republican Revolution was a relatively bloodless one, but Gingrich’s troops embraced the metaphor in full: As Garrett noted, “Republicans intend to hold what many privately call ‘War Crimes Trials’ to illustrate what they consider criminal behavior on the part of regulators.”

Illustration: Victor JuhaszThe Republican Revolution was a relatively bloodless one, but Gingrich’s troops embraced the metaphor in full: As Garrett noted, “Republicans intend to hold what many privately call ‘War Crimes Trials’ to illustrate what they consider criminal behavior on the part of regulators.”

Illustration: CF Payne

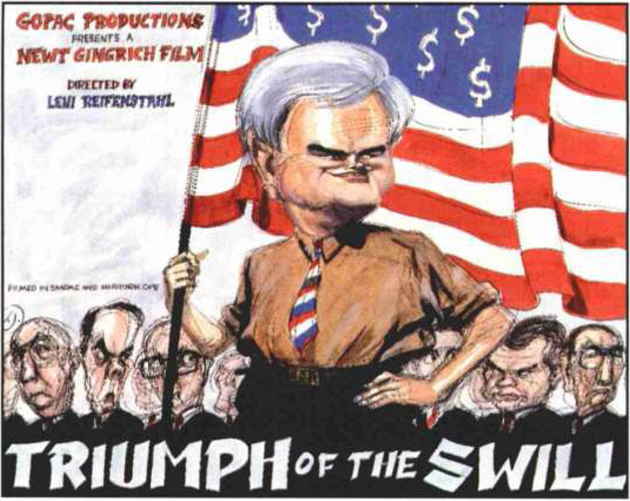

Illustration: CF Payne  Photo-Illustration: Daniel LeeBy the summer 1995, Gingrich was at the height of his powers and gearing up for a grand showdown with President Clinton. But the ethical shortcuts he had taken to get to that point were starting to catch up with him. Gene Simpson explored in detail how Gingrich used his own nonprofit college course to fuel his political action committee, GOPAC—turning it into “the ideal political slush fund, a Nixonian enterprise where huge unregulated sums sloshed about in secret.”

Photo-Illustration: Daniel LeeBy the summer 1995, Gingrich was at the height of his powers and gearing up for a grand showdown with President Clinton. But the ethical shortcuts he had taken to get to that point were starting to catch up with him. Gene Simpson explored in detail how Gingrich used his own nonprofit college course to fuel his political action committee, GOPAC—turning it into “the ideal political slush fund, a Nixonian enterprise where huge unregulated sums sloshed about in secret.”

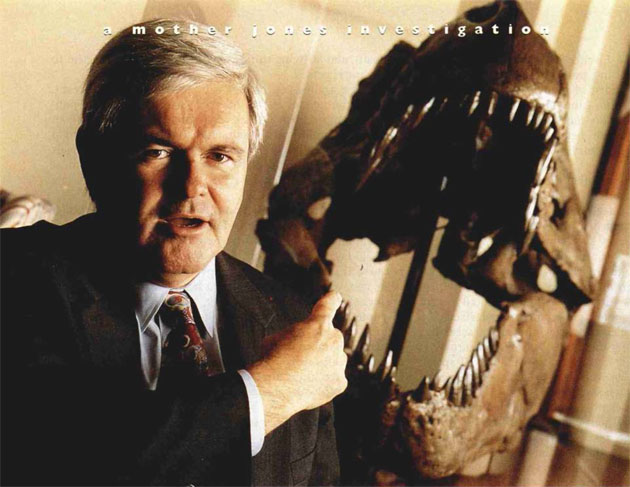

Photo: Sam KittnerFine, we’ll say it: Newt knew how to decorate an office. His plan to remodel government was more of a mixed bag, but he found admirers in strange places. As Klein mused in 1999, following Gingrich’s abrupt resignation from the House: “In 1996, Mongolia adopted the Republican model of smoke-and-mirrors reform, issuing a ‘Contract with the Mongolian Voter.’ Gingrich saw this as a victory in the “war of ideas.'”

Photo: Sam KittnerFine, we’ll say it: Newt knew how to decorate an office. His plan to remodel government was more of a mixed bag, but he found admirers in strange places. As Klein mused in 1999, following Gingrich’s abrupt resignation from the House: “In 1996, Mongolia adopted the Republican model of smoke-and-mirrors reform, issuing a ‘Contract with the Mongolian Voter.’ Gingrich saw this as a victory in the “war of ideas.'”

Illustration: Steve BrodnerGingrich’s magic trick—aside from, apparently, being able to spin around in tornado-like circles—was “the ability to shame others while displaying near absolute shamelessness.”

Illustration: Steve BrodnerGingrich’s magic trick—aside from, apparently, being able to spin around in tornado-like circles—was “the ability to shame others while displaying near absolute shamelessness.”

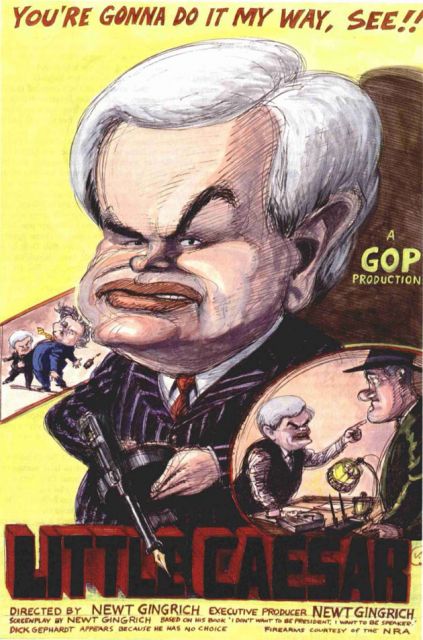

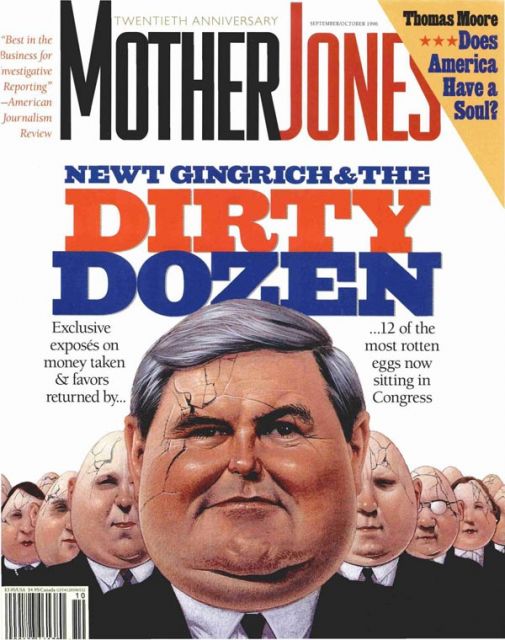

Cover of the September/October 1996 Issue. Illustration: C.F. PayneTwo years into the Republican Revolution, MoJo declared in 1996, Congress was open for business: “Newt’s recruits perfected the art of legislating favors for financial sponsors. Though often robed in Christian righteousness, these sponsors read like a list of vice peddlers. Gambling casinos. Tobacco giants. Gun lobbies. Big polluters. Arms manufacturers.”

Cover of the September/October 1996 Issue. Illustration: C.F. PayneTwo years into the Republican Revolution, MoJo declared in 1996, Congress was open for business: “Newt’s recruits perfected the art of legislating favors for financial sponsors. Though often robed in Christian righteousness, these sponsors read like a list of vice peddlers. Gambling casinos. Tobacco giants. Gun lobbies. Big polluters. Arms manufacturers.”

Illustration: Victor Juhasz

Illustration: Victor Juhasz

You don’t get to become speaker of the House without learning how to play hardball. Beers, granted exclusive access to the rising star in 1989, offered a glimpse of Newt’s temper: “Gingrich shuts her down with a sharp, angry, ‘Let me talk!’ His big silver head comes wheeling around, and he fixes his suddenly fierce eyes on me. ‘Mother Jones smeared me. All right? You are lucky that I believe you guys are trying something different.'”

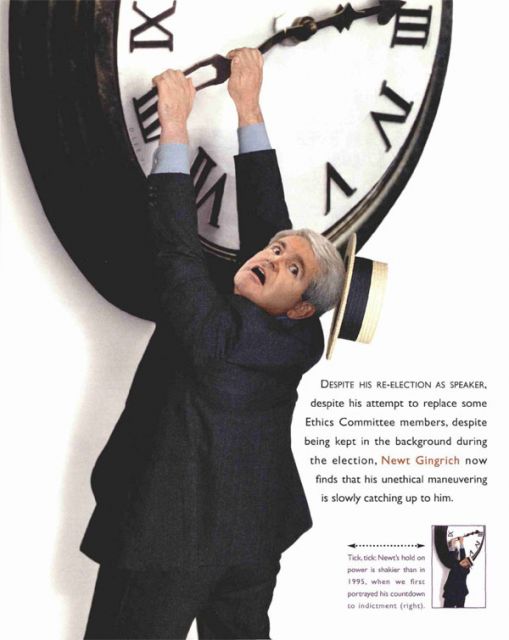

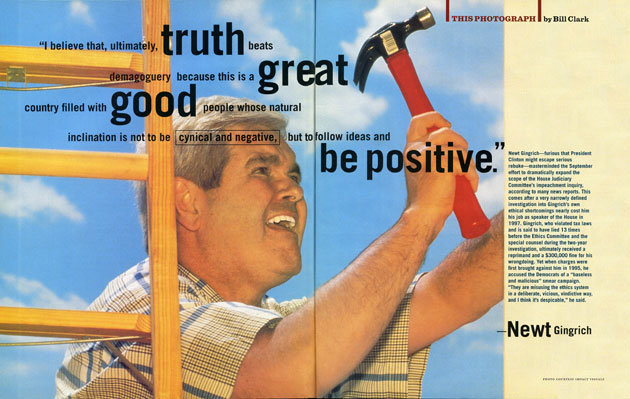

Photo: Bill ClarkSalt, meet wound: Newt resigned as speaker and left the House for good in 1998. He was slapped with an ethics violation even as he was pushing impeachment proceedings on President Clinton. It would take a while for him to rebuild his reputation—but perhaps not as long as we thought.

Photo: Bill ClarkSalt, meet wound: Newt resigned as speaker and left the House for good in 1998. He was slapped with an ethics violation even as he was pushing impeachment proceedings on President Clinton. It would take a while for him to rebuild his reputation—but perhaps not as long as we thought.

Illustration: Zina Saunders

Illustration: Zina Saunders

By 2009, things were looking up for the formerly disgraced speaker. As David Corn reported in the March/April issue of that year, his message of “tri-partisanship” was sinking in with the beleaguered Republican party. “Gingrich can come up with 15 ideas a day, [former aide Rich] Galen notes, realizing that only one is any good and that ‘over the course of a month, maybe one of them is actionable and you can build a project on it. The biggest sin in Newt-world is the sin of inaction.'” Bob Novak, the late conservative columnist, billed Gingrich as the right’s new “Moses.”

Of course, Moses never made it to the promised land.