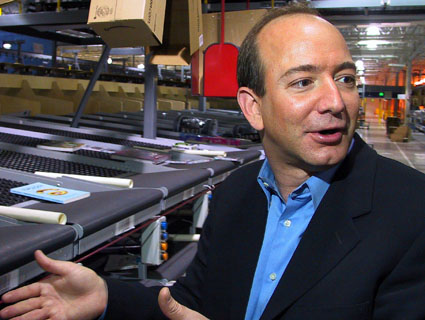

Elf: <a href="http://www.flickr.com/photos/69078621@N00/319188125">The Adventures of Kristin & Adam</a>/Flickr

Since June, I’ve been ruining my friends’ online-shopping lives. Back then, I reported on a vast warehouse in Ohio where goods bought from online retailers are sorted, boxed, and shipped to consumers. Unsurprisingly, this job does not pay well. A little more surprisingly, this job seems designed to crush employees’ spirits. During my visit, two people got fired within 10 minutes, one for talking to someone while he was working—”Where are you from?” was the offending comment—and one for going to the bathroom too much. So occasionally, and now more that it’s the holidays, my friends and family will call to complain that “Bleh, I want to order something from Amazon/Walmart/Staples/whatever, but I feel guilty about helping oppress workers.”

Why would online retailers be so mean? Well, in the case of many, they have helpfully outsourced interaction with workers. When Walmart started selling its merchandise on the internet, it turned to third-party logistics contractors, or 3PLs, experts who could handle the, uh, logistics, like warehousing and transportation, of online sales. Take Exel, for example, the largest 3PL in the country, and a subsidiary of Deutsche Post DHL, one of the largest companies in the world. Exel alone has 86 million square feet of warehouse all over North America and processes literally millions of goods every single day. Other retailers directly perpetrate the oppression. Amazon.com made headlines earlier this year when 20 current and former employees of its Breinigville, Pennsylvania, warehouse told the local Morning Call that workers were fainting in stifling heat and getting yelled at for not meeting ridiculously high productivity goals and generally being “treated like a piece of crap.” Employees who were sent home with heat exhaustion were disciplined; a local ER doc eventually called OSHA and reported “an unsafe environment.”

Either way, many of the people actually loading and unloading trucks, packing boxes, and pasting labels work not for retailers, or for 3PLs, but for yet another company: temporary staffing agencies. When an online retailer (especially one that doesn’t actually make anything) wants to wring out the most profit possible, it helps to have a labor pool that is on demand, so it can order the exact number of humans it needs to fill that day’s number of orders if the humans are working at top capacity. That way, workers can’t unionize or be legally entitled to decent benefits. That way, the online retailer can give them outlandish productivity goals, like hundreds of orders and thousands of items per day apiece—and when workers burn out, just replace them with the next temp, who can join the rest of the ranks living in fear that they won’t make their numbers and might be incessantly berated for it, or simply fired. Even if you meet the outlandish goals, don’t necessarily expect to be rewarded by say, a real job. As with so many in the industry, the warehouse in Ohio are mostly “temps”—even though some of them have been working in the same place for more than a year.

Lots of people are “temporary” pickers and sorters and shippers year-round. Annual internet retail sales in the United States are estimated to hit $197 billion at year’s end; they’re projected to grow 10 percent every year to $279 billion in 2015. And during the holidays a lot more people sign up—to handle the Christmas rush, the biggest retail-shipping warehouses hire thousands of extra employees each. That’s each warehouse mind you; Amazon for example had 52 in 2010, with plans to complete another 17 by 2012. And because Christmas is a deadline that consumers take very seriously, peak-season temps have it a little bit worse. Often, they can’t request any time off during the holidays. If they miss Thanksgiving, or Christmas Eve, they can be fired. Overtime is generally mandatory, even if that means five 12-hour days in a row. Doing anything for five days of 12-hour shifts is tough, but particularly when that thing is standing in one spot at a conveyor belt repeatedly stuffing inflatable air pockets into boxes, or running up to 15 miles a day around a vast warehouse in order to retrieve the items for those boxes, bending over to grab them off floor-level shelves literally hundreds of times a day, while supervisors meticulously keep track of how many items every employee picks and let them know when they’re not moving fast enough, not good enough. Hurry up, customers are waiting. Santa’s special helpers can’t be permitted to take personal time off, or time to go to the bathroom except during a couple of 15-minute breaks, or to have enough off-work hours in their day to get laundry done or eat dinner with their kids. It’s Christmas, goddammit.

So while I don’t want to have to change out of my pajamas to go shopping, either, and I fully expect the goods I order off the internet to materialize at my front door in about the amount of time it would take them to be transported from the Starship Enterprise, I’m just sayin’. Like I tell people who are unfortunate enough to be friends with me: It’s worth considering how the hell those goods get to you, so fast, and for free, when the company you bought them from is posting profits in the millions, or even, in the case of Amazon, billions. Chances are, it’s via the people who worked for the small businesses we ruined when we were saving $4 by buying stuff off the internet, people performing dangerously repetitive or otherwise ergonomically unsound jobs in a cold, shitty, emotionally abusive warehouse for very little money and very few benefits, the kind of conditions people endure only because it’s their last resort. It’s worth considering, because one of the reasons those conditions can so widely prevail is that no one ever does.