Illustration: Edel Rodriguez

“Dear Mr. Cole,” the letter began. “My name is Jerry Wayne Johnson. I’m presently a Texas prisoner. You may recall my name from your 1986 rape trial in Lubbock.”

Ruby Session was shaking as she read on. The year was 2007, and the letter was addressed to her son Timothy Cole. “I have been trying to locate you since 1995 to tell you I wish to confess I did in fact commit the rape Lubbock wrongly convicted you of.”

Ruby sat down, stood up. A picture of Tim in a tuxedo, taken at his junior prom, smiled from the mantle. Before his trial the prosecutor had offered him a deal to plead to lesser charges. “Mother,” Tim had said, “I am not pleading guilty to something I didn’t do.” He was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Thirteen years later, he died behind bars.

The Texas criminal-justice system has long had a harsh reputation, but it has drawn renewed scrutiny with Gov. Rick Perry’s run for president. During the past 11 years, Perry has presided over 238 executions, including the infamous case of Cameron Todd Willingham, who was put to death based on a dubious arson investigation. In a September debate, Perry famously said that he had lost no sleep over the possibility of an innocent man being executed on his watch.

Yet during his governorship, Texas has exonerated no fewer than 56 people. All had served years, sometimes decades, in prison; five were on death row. As Perry sees it, these exonerations don’t suggest a problem with the system—they demonstrate that it’s working. “We have a very lengthy and methodical process of appeals,” he said in March 2010. “And that is a great and good mark for Texas.”

Perry made those remarks during an extraordinary ceremony in which he handed down the first posthumous pardon in Texas history. Timothy Cole, imprisoned while a 26-year-old student at Texas Tech University, had been failed by the justice system at every turn. But what makes his story particularly gut-wrenching is that he perished in prison even as the real rapist, Jerry Johnson, tried repeatedly to confess to the crime. By the time Johnson’s story was heard, Cole had been dead nearly a decade.

The tale of Tim Cole and Jerry Johnson, which I investigated for more than a year, reveals a system in which an innocent man, once convicted, has virtually no chance of redemption—even with the guilty man fighting for it. For the thousands of Americans spending years of their lives in prison for crimes they did not commit, the odds couldn’t be much bleaker.

On the night of March 24, 1985, Texas Tech sophomore Michele Murray was parking her car near campus when a tall black man in a yellow terry-cloth shirt approached and asked her for jumper cables. He reached into the window, unlocked the door, and shoved Murray to the passenger side. He forced her head down onto the seat and held a knife to her neck. He told her that if she kept screaming she wouldn’t come back alive.

He smoked while he drove. He asked her name, her major. He took her to a field outside of town and raped her. He smoked when he was done. Then he made her drive him back to town, stole her jewelry and money, and took off on foot.

It was the fifth rape on or around the Texas Tech campus in four months. Female students were frantic. Police were on high alert. In all the cases, a young woman was approached in her car by a tall black man—identified as a smoker by three of the victims—who drove her outside of town at knifepoint and raped her. Composite sketches of the “Tech rapist” in the local papers seemed to change daily. Only about 500 of the 22,000 students on campus were black, and it became a grim joke among them: Don’t walk around campus at night or they’ll say you’re the rapist.

Jerry Johnson at Tim Cole’s exoneration hearing in 2009 Harry Cabluck/AP Photo

Jerry Johnson at Tim Cole’s exoneration hearing in 2009 Harry Cabluck/AP Photo

The shoddy police investigation and sensational trial that followed were capped by a remarkable coincidence. When Cole was taken to the Lubbock County Jail after his sentencing, in September 1986, the real rapist was right there in a nearby cell. Johnson, who was awaiting trial for two other rapes and a murder, had followed Cole’s story in the paper. He listened to Cole cry. “It was terrible to learn that Tim was…on trial for something I knew he hadn’t done,” Johnson wrote to me in a letter in 2010. “Seeing him cry his first night in jail and seeing him leave to be taken to prison was difficult, I cried.” But he did nothing. He was already facing the death penalty. “I knew it wasn’t good to say anything before I went to trial.” Later he would learn in the prison library that there was also the statute of limitations to consider. So he kept his mouth shut—for nine years.

Johnson grew up in the 1960s on the east side of Lubbock, an impoverished neighborhood of cotton fields and ramshackle houses. He was raised mostly by his great-grandmother; his mother, JoNell Johnson, and grandmother lived nearby, as did his estranged father, Lorenzo Harris. “Sometimes Jerry would come over to the house, be out there at the fence,” Harris recalls. “He knew I was his daddy, but my wife would run him off.”

Read Jerry Johnson’s full letter here.

Read Jerry Johnson’s full letter here.

Johnson was 12 years old the night in 1971 when his mother shot and killed a boyfriend after he assaulted her with a pool cue. (She was eventually sentenced to 10 years’ probation.) He dropped out of high school but managed steady employment in blue-collar jobs. He had two children and got married in the early 1980s. But by 1985, Johnson says, he had lost control. “Obviously I had a psychological breakdown,” he says. “Why, I don’t know.” When pressed, he demurs. “I cannot form a reason or cause for my actions.”

Johnson raped Murray in March, he now admits, but investigators never pursued him as a suspect. He was arrested that July, however, for raping a woman he met at a party. In October, out on bond, he was arrested for kidnapping and raping a 15-year-old girl from Estacado High School; two years later, he was convicted of those crimes and sentenced to life in prison. He was also charged with murdering an insurance saleswoman, but those charges were dropped.

Johnson and I had been corresponding for about a year when we finally met in March 2010, in a bright, empty visitation room at the Price Daniel correctional facility in Snyder, Texas. Tall and thickly built, Johnson was dressed in the facility’s standard white cotton shirt and pants and was soft-spoken and polite. Now 52, Johnson is certain he’ll never be free again. “There’s a lot of people live a false life; everything they do is a lie. Never no honesty. And you have those people that go to their death like that. I don’t want to go to mine like that.”

When I ask him about the four other Texas Tech rapes—so similar to Murray’s but never solved—he says, “I don’t have a comment about that stuff.”

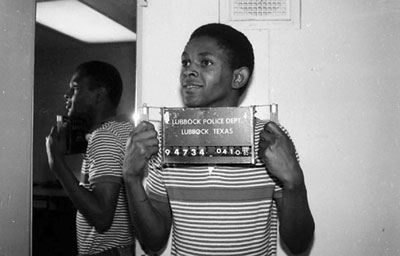

A Lubbock police photo of Tim Cole’s booking in April 1985. Lubbock Police Department, Courtesy Cole Family

A Lubbock police photo of Tim Cole’s booking in April 1985. Lubbock Police Department, Courtesy Cole Family

Hill View Drive, the leafy middle-class block where Tim Cole and his six younger siblings grew up, was overrun with kids. Cole was a big brother to them all: He organized sports games, led neighborhood jogs, and gave advice. “Tim used to always tell me to be the best I could be,” recalls neighbor Leon Warren. “He would tell me, ‘Make sure you go to a major university and do good,’ and ‘You can make it.'”

From an early age Cole was sure he would play basketball in college—despite his severe asthma, he loved sports—study business, and own his own company. He went to Texas Tech and the University of Texas-San Antonio before joining the Army in 1981; in 1984, he moved in with his younger brother Reggie in Lubbock to go back to school at Tech. He studied long hours, worked as a dishwasher, and partied occasionally. In January 1985, he was robbed outside a party, and when he reported the crime, police found some marijuana and a gun in his pocket. (He was charged with a misdemeanor.)

One night that April, outside a pizza parlor, Cole chatted up a woman named Rosanna. After Cole had driven away, she got into her partner’s squad car, sure she’d found her mark. Rosanna was an undercover police officer—bait for the Tech rapist. Two days later, a detective stopped by Cole’s place. He needed to take a picture, he said, for the investigation of the robbery Cole had reported. Cole looked straight into the camera and the detective snapped a Polaroid.

Later that day, an officer brought a photo lineup over to Murray’s dorm. All but one of the photos were mug shots—men looking away from the camera, holding their book-in cards. Murray hesitated. She pointed to the Polaroid of Cole. “I think that is him,” she said.

“Are you positive?” asked the officer.

“Yes,” she said. “I am positive.”

Eyewitness identification has long been the most powerful tool in a prosecutor’s arsenal. Even when there is a dearth of forensic evidence, juries are swayed by a victim’s certitude—how could she forget the face of the person who raped her? But researchers are learning just how often eyewitnesses are wrong: Nationwide, incorrect identification was a factor in the convictions of more than 75 percent of people eventually exonerated by DNA. Gary Wells, an Iowa State University psychology professor who has studied the issue for decades, says the Lubbock police did exactly the things that can influence an eyewitness to choose the wrong guy. In a good lineup, he says, the witness must be warned that the perpetrator might not be in the lineup at all. “The tendency is to pick the person who looks most like the perpetrator—relative to the other lineup members,” Wells explains. He also argues that the process must be double blind: Neither the officer nor the witness should know which photo shows the true suspect. “It’s so natural for the lineup administrator, if you pick the person they had in mind, to smile, react, to reinforce.”

Read Tim Cole’s full letter here.

Read Tim Cole’s full letter here.

For his 2011 book, Convicting the Innocent, University of Virginia law professor Brandon Garrett examined hundreds of DNA exonerations and found that in at least a third of the cases the victim was shown a “stacked lineup” like Cole’s, where the actual suspect was highlighted. Even if victims were uncertain initially, he says, “by the time of trial, almost all of them were absolutely sure they were identifying the right person.”

At trial, Cole faced a jury that included one member whose ex-wife had recently been a victim of sexual assault. His brother Reggie and his friends testified that on the night of the rape they were home, partying, while Cole sat at the dining room table all night studying. Reggie also testified that his brother never smoked due to his asthma. But the prosecutor, Jim Bob Darnell, portrayed them as liars who would say anything to save Cole.

No evidence tied Cole to the rape. His attorney, Mike Brown, brought up Jerry Johnson several times and even submitted a picture of him as evidence. Johnson had been charged with two rapes by then, and Brown recognized similarities with those assaults. It didn’t matter. “What the jurors saw, and heard, was a courageous young woman unshakeable in her belief of who had raped her,” District Court Judge Charlie Baird would write many years later in exonerating Cole. “What they did not know was how that belief had been shaped and formed by the police.”

Ruby Session chokes with sorrow as she recalls the moments after her son was sentenced, when he fell to the courtroom floor and cried. She got off her chair and down on the floor with him. She hugged him and rocked him. “My son, a 26-year-old man, lying in his mother’s arms. And that’s all I could do. And that’s the last time my baby was in my arms like that.”

Johnson’s plan from the start, he says, was to contact Cole directly. “I believed at some point I would connect with him,” he says, “and he would probably send a lawyer to talk with me and try to get himself out.” He began by writing letters to everyone he knew in prison, asking if they’d run into a guy named Tim Cole. It was a fool’s errand—Cole could have been among any one of more than 100 prison units. But Johnson says he couldn’t think of another way to find him.

Read Tim Cole’s full letter here.

Read Tim Cole’s full letter here.

Johnson did not approach the authorities until years after the statute of limitations for the Murray rape had run out. Then, in 1995, he petitioned the court to appoint an attorney for him so he could confess. He copied the petition both to Brown and the district attorney. He got no response.

For five years Johnson worked on his own appeals and helped other prisoners with their legal paperwork. “Never during this time period did I not think about Tim and the petition or a way to contact him,” he says. But he took no further action.

Then, in 2000, Johnson sent the court a letter: “Judge I believe I have properly raised an important issue the court should have long ago addressed. Certainly the convicted man would want to see his name finally cleared.” In January 2001, he got a two-line order in the mail, with no explanation. It simply said, “Denied.”

Most appeals in Texas criminal cases end up at the Court of Criminal Appeals, which consists primarily of former prosecutors elected to the bench. The court rarely reverses a case, even in the face of glaring errors or unfairness—in one case, it upheld the conviction of a man cleared by DNA evidence—and its conduct has prompted the US Supreme Court to rebuke it several times.

The Texas Board of Pardons and Paroles is similarly stacked with former law enforcement officials and prosecutors. They rarely meet in person, typically passing a file from one office to the next for an up-or-down vote. The inmate has no right to demand a hearing from the board or receive an explanation. “Either they hire a lawyer or they pray to God,” says William T. Habern, former executive director of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Project. “They can write something in if they want to, but who do you think the board is going to believe? Some inmate?” When Cole was up for parole in 1996, Texas considered 1,024 cases classified as SB-45, or “Extraordinary Vote,” which include certain types of sexual abuse and violent crimes, and require a vote by the full board. Among those 1,024 cases, not a single prisoner was granted parole and released.

Until the advent of DNA technology, wrongful convictions were thought to be extremely rare. But as the number of DNA exonerations rises—at least 281 as of this writing—we confront the uncomfortable truth that the number of innocent people behind bars is far higher than we realize. The vast majority of DNA exonerations are in rape cases. In many felony cases—robberies, shootings, murders, drug-related crimes—there is no DNA to test. Even in rape cases, forensic evidence often is lost or destroyed.

DNA testing provides false assurance, then, that there is recourse for people failed by the justice system. What it really does is underscore what a true solution would require: a system equipped to deal with the significant number of people locked up for crimes they did not commit. Experts say that number is nearly impossible to nail down. But a conservative estimate, extrapolating from research on eyewitness identification and DNA exonerations, ranges from at least a few thousand to more than 20,000 people wrongly imprisoned nationwide.

A string of devastating stories has put Texas justice, in particular, under a cloud. In addition to Cole’s postmortem exoneration and the execution of Cameron Todd Willingham, chronicled in The New Yorker in 2009, there is also the case of Anthony Graves, who served 18 years for a gruesome murder while the true killer confessed again and again. Graves was finally freed in 2010 following a Texas Monthly exposé.

Cole, Willingham, and Graves were all convicted under prior Texas governors. But Perry has done little to improve the state’s criminal-justice system, which has almost a million people in its grip. In 2001, he vetoed a bill banning the execution of the mentally disabled. In 2003, he cut the prison system’s budget by $230 million, slashing education programs, drug treatment, and food; when an independent auditor warned that was untenable, Perry cut the auditor’s office too. In 2007, his administration backed a bill making some child sex offenders eligible for the death penalty. While Perry has signed legislative reforms covering eyewitness identification and access to DNA testing, the system still offers scant options for the many people imprisoned for crimes they did not commit.

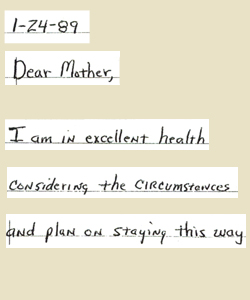

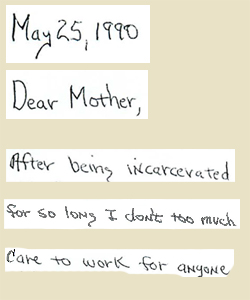

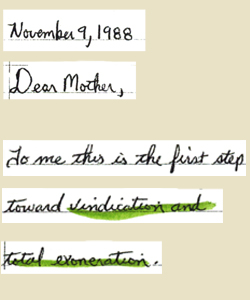

During his years behind bars, Cole tried to keep himself busy. He took business classes, corresponded with family, and subscribed to magazines like Nature, Jet, and Money. “I want to become vindicated as well as totally exonerated in order to receive a Pardon from the Governor of the State of Texas in order to place it on my wall in my future office or the den of my home,” he wrote in one letter. As he told his mother to stay strong and his brothers to study hard and go to college, he repeated this phrase like a mantra: “vindicated and totally exonerated.”

Read Tim Cole’s full letter here.

Read Tim Cole’s full letter here.

In 1991, Cole won an appeal on procedural grounds, but the Court of Criminal Appeals still ruled his conviction would stand. In 1992, his case was considered by the pardon and parole board. He was asked if he was sorry for what he did. He said he didn’t do anything. He was denied parole. He kept up on emerging DNA technology, and in 1995 he wrote a letter to the newly founded Innocence Project in New York City, but the organization did not take his case. In 1996, he was denied parole again.

Cole was running out of options. The dust, heat, and poor ventilation had brought back his asthma, and he was shuttled between hospital wards and prison cells—twice he was found unconscious and rushed to the emergency room.

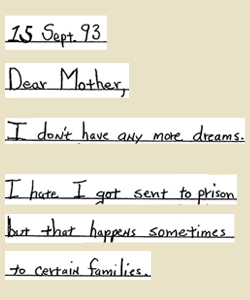

In Cole’s letters, upbeat sentiments like “I will continue to patiently wait for this unfortunate matter to resolve itself” began to give way to “How far does this miscarriage of justice have to go before I can prove my innocence?” And finally, “I don’t have any more dreams.”

On December 2, 1999, Tim Cole was on his way to the infirmary with chest pain when he collapsed on the floor and never woke up again. He was 39.

There is no formal legal means in Texas to confess to a crime for which someone else has been convicted. “I guess you can contact whatever law enforcement agency handled the case,” says Lubbock District Attorney Matt Powell. That, of course, is precisely what Johnson did when he copied his petition to the district attorney in 1995.

“Here you’ve got a guilty guy saying, ‘I did this crime,'” says Jeff Blackburn, chief counsel for the Innocence Project of Texas. “All the ears went deaf and all the eyes went blind.”

The Innocence Project of Texas itself receives thousands of letters each year from inmates claiming to be innocent, and Blackburn says that has fine-tuned his BS detector. Even guilty prisoners have nothing to lose by trying; indeed, Johnson wrote to the Innocence Project about Cole in 2005, but his confession was buried in a diatribe about other issues and got no traction. Johnson also fired off letters to newspaper reporters, law professors, and even a private investigation firm. Some were angry rants about Lubbock law enforcement; some asked for help with his own innocence claim; some expressed a wish to confess. Many of the letters contained all these things, perhaps making them difficult to take seriously.

But then, in 2006, Cole’s former attorney, Mike Brown, received one of Johnson’s letters. (Brown says he doesn’t recall ever receiving a copy of Johnson’s 1995 petition.) He forwarded it to Powell, who sent an investigator to look into it, not expecting much.

By April 2007, Johnson still had gotten nowhere. But then, while looking through some old papers, an idea struck him. He had his stepmother look up Cole’s jail book-in card, which contained Cole’s home address. Soon afterward, Ruby Session held Johnson’s letter to her son in her hands.

After recovering from the shock, Session sent a copy of Johnson’s letter to the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal, which during her son’s trial had run his name under headlines referring to the “Tech rapist.” Now, the paper noted: “The family of Timothy Brian Cole, who was 26 when he was convicted of rape in 1986 and died in prison while serving a 25-year sentence, hope a letter they received last week from a man imprisoned for two brutal rapes around the same time will finally clear the former Tech student’s name.”

Read Tim Cole’s full letter here.

Read Tim Cole’s full letter here.

Reading the paper in his cell, Johnson was stunned. He’d had no idea Cole had died. “I remember not coming off my bunk the rest of that night,” he says. “I reread and reread that article.”

The paper also quoted a skeptical Jeff Blackburn of the Innocence Project. “We’ve had several of these guys,” he said. “None of them have checked out.” Cole’s youngest brother, Cory, took exception to Blackburn’s comments and called to tell him. The two men soon became friends. After the Innocence Project sent a lawyer to interview Johnson, Blackburn agreed to represent the family to clear Cole’s name. With public pressure mounting, the DA’s office discovered that the original rape kit was still in storage; it conducted DNA testing with Johnson’s cooperation and soon confirmed that he was indeed the rapist.

The proceeding to posthumously exonerate Cole took place in Austin in February 2009. Michele Murray (now Mallin) was there to confront Johnson for the first time since 1985. She and Session hugged and cried, and she told Johnson that she hoped he’d suffer for what he’d done to her, and to Cole. “No man—no person—deserves what that young man got,” she said.

Cole’s brother Sean rocked in his chair and cried as Judge Baird read his ruling: “I find to a 100 percent moral, factual, and legal certainty that Timothy Cole did not sexually assault Michele Murray Mallin.”

Session listened, expressionless.

“I find that Timothy Cole’s reputation was wrongly injured, that his reputation must be restored, and that his good name must be vindicated.”

Cole’s brother Reggie pumped both fists in the air.

“I find that Tim Cole shall be and is hereby exonerated and freed from any guilt or blame related to the sexual assault of Michele Murray Mallin.”

It was all over the news. Texans in their living rooms heard about it, the Board of Pardons and Paroles heard about it, legislators heard about it. The Tim Cole Act, establishing one of the nation’s most generous compensation programs for the wrongfully convicted, passed three months later.

On a windy day in March 2010, Rick Perry, impeccably groomed in a camel-colored jacket and green tie, stood in a hotel conference room in downtown Fort Worth. Perry quoted from Proverbs and flashed a solemn grin around a room filled with family members, reporters, and exonerated convicts. “Ruby, it means the world to me to be here today to look you in the eye and tell you that your son is pardoned,” he said. He commended her for her “graceful persuasiveness” and called her a “wonderful, loving, Christian woman.” Then Perry leaned in to hug her, adding, “And I want to say: I love you.”

But if Perry learned anything from the exoneration of Tim Cole, it was not in evidence 18 months later, when he went on national television and declared his absolute faith in the Texas justice system. Ruby Session clearly had not shared that faith as she received Perry’s pardon, somber-faced. That night she went home and, next to her son’s junior-prom picture, carefully placed on the mantle the piece of paper he had died waiting for.