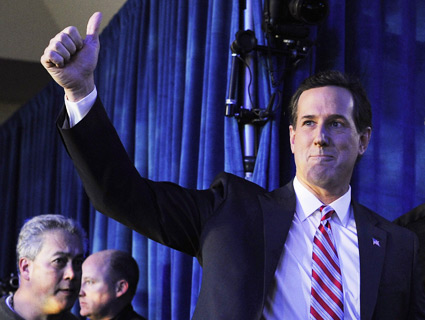

2012 Republican presidential candidate Rick SantorumZhang Jun/Xinhua/ZUMA Press

Rick Santorum likes to brag about how he helped a poor local company fight big, bad government regulations on greenhouse gas emissions. “My grandfather was a coal miner,” Santorum said at a debate in New Hampshire this week. “So I contacted a local coal company from my area. I said, look, I want to join you in that fight. I want to work together with you.”

But Consol Energy, the company for which Santorum was a “consultant,” wasn’t some bare-bones local outfit—it’s one of the largest coal mining companies in the United States, and its largest shareholder is the German utility RWE. And Santorum wasn’t doing volunteer work: He was paid quite handsomely for his services, to the tune of $142,500 from 2010 to August 2011. He only ended his role with Consol when he launched his presidential bid last spring.

Santorum’s relationship with the coal company began long before his consulting gig; Santorum and Consol had a mutually profitable association during Santorum’s tenure in the Senate, too. Consol donated more than $73,800 to Santorum during his time as a legislator while simultaneously spending more than $1 million lobbying Congress on pollution limits, mine reclamation, worker health benefits, and tax policy, according to lobbying disclosure forms filed with the US Senate Office of Public Records.

In the most recent congressional debate over a climate bill—the one for which Santorum “volunteered” his services—Consol spent $10.24 million on lobbying, a major increase over its lobbying expenditures in previous years. Much of that money was spent to defeat legislation to cap greenhouse gas emissions.

Greenhouse gas regulation wasn’t the only area where Santorum’s legislative agenda mirrored Consol’s top lobbying priorities. In 2006, Santorum authored a provision for a tax bill that would have created a tax credit for “synfuel,” which included coal bed methane, as Greenwire reported at the time. Synthfuel is made by drilling into coal seams to extract methane, a form of natural gas, and Consol is a “leading producer” of the product.

Another priority for Consol was passing the 2005 Energy Policy Act, a bill criticized for its numerous handouts to the coal, oil, and gas industries. Santorum voted for the bill and was an enthusiastic supporter. He was particularly fond of the millions of dollars the bill allotted for so-called “clean coal” technology—another major priority for Consol’s lobbyists.

Consol also lobbied the Senate on the Environmental Protection Agency’s mercury emission standards during Santorum’s time in Congress. In 2003, the Bush administration released new Clean Air Act rules that failed to adequately cut toxic emissions from coal-fired power plants and other major industrial sources (a court threw out the rules for having too many loopholes). When the Senate tried to pass a resolution blocking the faulty rules from taking effect, Santorum sided with the administration and with Consol. During his time in the Senate, Santorum also lobbied Bush’s EPA to ease rules for sulfur dioxide—the emission that causes acid rain—for plants that burn waste coal.

“He certainly racked up one of the most anti-environmental records in Congress in his time there,” says Navin Nayak, the senior vice president for campaigns at the League of Conservation Voters. Nayak’s group scores lawmakers annually on their voting record, and Santorum earned a lifetime score of just 10 percent—among the lowest in the Senate. “He was consistently on the side of polluters.”

It’s not entirely clear what Santorum did during his tenure as a Consol consultant, which started in 2007 after he was defeated for reelection. A spokesperson for the company told the New York Times he was hired “to provide strategic counsel on a variety of public policy-related issues.” Although he was never registered as a lobbyist, former legislators can still be adept at maximizing their clients’ influence without actually having to officially register as lobbyists under the law.

“The definition [of lobbyist] was designed to give a reasonable enough definition so that people who lobby would have to register,” says Bill Allison, Editorial Director at the Sunlight Foundation. “What happens is canny operators like Newt Gingrich and like Rick Santorum are able to avoid the lines drawn that would force you to register…Obviously these folks are trying to influence the federal government.”

His legislative experience is exactly why the company says it approached him about a consulting gig. “Given his long and well-documented efforts aimed at providing American consumers with affordable energy, CONSOL Energy engaged Senator Santorum to provide strategic counsel on a variety of public policy-related issues,” Consol spokeswoman Lynn Seay told Mother Jones in an email. She did not elaborate explain which specific issues the former senator focused on.

Santorum’s connections to Consol were profitable for his former aides as well. Former Santorum staffers Tommy Johnson and Kevin Roy also went on to become lobbyists for Consol after their boss lost his Senate seat. Johnson was an in-house lobbyist at the company and Roy worked on Consol’s behalf at Ikon Public Affairs, a lobby shop that Consol paid $40,000 to promote its interests in Washington in 2009.

Santorum, whose description of Consol during the New Hampshire debate made it sound like a corner store owned by your grandparents, clearly saw his primary role at Consol Energy as influencing the legislative process. “I engaged in that battle,” he said Saturday. “And I’m very proud to have engaged in that battle.”