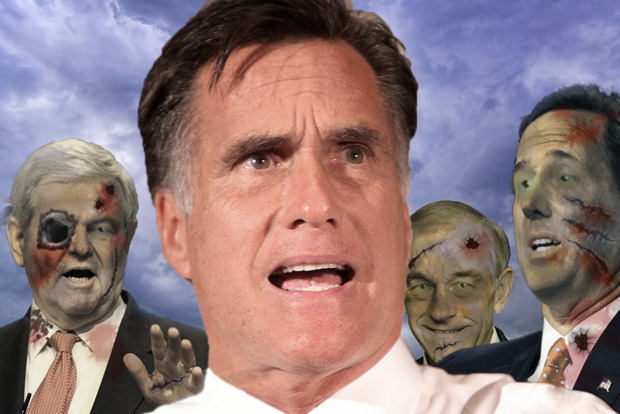

Photoillustration: <a href="/authors/dave-gilson">Dave Gilson</a>

Mitt Romney faces the fundamental problem confronted by all zombie hunters: How do you kill that which is dead already?

The Not-That-Super Tuesday contests showed that Romney remains the front-runner—he pocketed many more delegates than the rest of the pack and squeaked out a victory in the much-prized swing state of Ohio—but the results will not send the others packing. Santorum won Oklahoma, Tennessee, and North Dakota, and Newt Gingrich triumphed in his home state of Georgia. Romney’s crew will now be telling reporters that the delegate disparity has become too wide for the semi-surging Santorum to bridge. But the other candidates will keep on pursuing Romney like the undead trodding after the barely living.

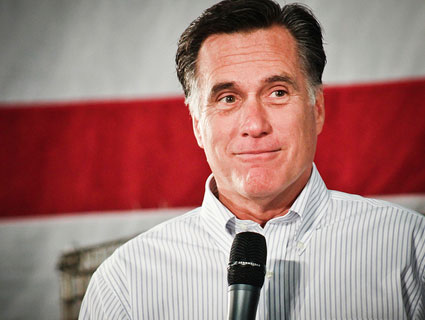

The fundamental reality of the Republican GOP 2012 death march is that none of the candidates ought to win. Romney is a robot reprogrammed to appeal to a base that isn’t keen on a former Massachusetts governor who once proudly proclaimed his fealty to moderation and progressivism. It’s taken millions of dollars (much of that spent on mud-encrusted negative ads) and a Titanic boatload of cajoling from the GOP establishment to raise Romney to the mid-30s in Republican polls and election results. And, for what it’s worth at this point, in national surveys this clubhouse buddy of NASCAR team owners trails a president who is presiding over an anemic economy at a moment when nearly 60 percent of the public fears the nation is stumbling in the wrong direction.

Yet Romney is heads, hair, and broad shoulders above what remains in the Republican field. (Woody Allen might have predicted this race in his 1977 film Annie Hall, when he quoted the old joke about two elderly women at a Catskills mountain resort. One says, “Boy, the food at this place is really terrible.” The other one says, “Yeah, I know, and such small portions.”) After Michele Bachmann, Rick Perry, Tim Pawlenty, Jon Huntsman, and Herman Cain self-deported from the circus, GOP voters were left with—besides Romney—a maniacally self-aggrandizing former House speaker with more baggage than a 747 who is better suited for a reality TV show than residency at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, a little-known senator who lost his last election (in his home state) by a historic margin and who seems to believe Cotton Mather was a wimp, and a conspiracy theorist who supports drug legalization and decries American empire (positions not usually embraced by garden-variety Republicans).

They are each damaged goods. (Rick Santorum and Newt Gingrich were, in earlier times, even pronounced politically dead.) In a perfect—or less imperfect world—none of the Republican Final Four should win the crown. But absent some made-for-HBO-movie surprise development, one of these fundamentally flawed candidates will win.

Though Romney is on the glide path, as turbulent as it may be, toward success, he needs to reach that destination as soon as possible. His approval rating among those needed-in-November independent voters has been in a free-fall, as he has veered to the far right and blundered his way to ugly and close wins in the GOP primaries. This race is killing his image as a competent Mr. Fixit for the economy. Instead, he has come across as a craven 1-percenter who is neither a man of principle nor a man of the people.

He has created a wide divide between himself and those middle-of-the-road voters, and the longer he must vie with Santorum and Gingrich for the hearts of his party’s die-hard ranks, the deeper this divide gets. Romney obviously is not intimidated by the prospect of reshaping voter impressions of him. Yet if this catfight on the right continues for weeks and months, Romney runs the risk of creating an impression with independent voters that will be indelible—one that he cannot wash away with a pivot (graceful or not) back to the political center he once cherished.

Romney backers and some GOPers in Washington have been insisting in recent days that a prolonged, knock-down GOP slugfest will not harm Romney for the fall campaign (presuming he prevails). They point to the extended 2008 duel on the Democratic side and assert that Barack Obama’s bitterly fought face-off against Hillary Clinton toughened up the Senate rookie for his match against John McCain. But the Obama-Clinton bout did not turn off voters and depress the popularity of either candidate. The crowds at Obama’s rallies grew. Independents were not alienated. Obama’s triumph over his better-known rival enhanced his standing. Excitement bloomed.

This year, Romney and the GOP are not accruing such benefits from their tussle. Voters—including Republicans—are losing interest in the race as it slogs on. And Romney is hardly improving as a candidate, while steadily committing gaffes that seem ghost-written by Occupy Wall Street pranksters. His off-Broadway run is threatening to ruin the production.

Romney needs to break away from the freak show. Which brings us back to the all-important zombie question—how can he rid himself of his flesh-eating pursuers? Despite his Super Tuesday gains (and advantages in money and organization), it may not be easy—and not just because Santorum can stake a claim to a modicum of momentum. Due to new Republican party rules, more states this cycle are awarding delegates on a proportional basis. The GOP primaries used to be dominated by winner-take-all contests. Under this revised system, the three non-Romneys each have great incentive to remain in the race—and bag delegates that might become bargaining chips, should Romney reach the convention in Tampa ahead of the zombie pack but still shy of the 50-plus percentage of delegates needed to claim the prize. (It is possible that any of these three could end up with enough delegates for use in a backroom deal that would land Romney on the GOP throne.)

Also, given Romney’s less-than-stellar performance as the candidate, it would not be unreasonable for the others to stick around just in case of an unlikely-but-not-inconceivable Romney implosion. And it’s not bad for book sales, Fox News show-hosting opportunities, or mailing-list development to remain in the GOP muck pit, even (for Santorum and Gingrich) at the possible cost of being further pilloried by pro-Romney super-PAC ads.

Romney doesn’t have much leverage over them. Zombies are hard to reason with. They’re already dead. They’re tough to bribe. They want to kill you. Santorum need only look at Mike Huckabee to see that there’s life (and great profit) as a social conservative leader following a presidential race. Gingrich has, undoubtedly, already calculated how much his lecture fees will rise with each week he stays in the race. With his alternative-reality crusade, Ron Paul can continue to bolster and build a fiefdom he can hand over to son Rand (and perhaps avoid the estate tax). Pressure from Romney’s pals in the Republican establishment (Vin Weber, this means you!) may not be sufficient to trump these other possible benefits.

Super Tuesday yielded more delegates for Romney—and delegate-snatching is the name of the game. But it did not alter important fundamentals. Romney remains a weak candidate in a weak field. And he has yet to figure out a better strategy of coping with zombies than the one adopted by Bill Murray’s character in Zombieland: pretend to be one yourself.