Part of a Powerpoint lesson on neighborhood watch programs by the Sanford, Fla., police department: City of SanfordAt 9:02 p.m. on September 21, 2005, he called 911 about a stray dog on Skyline Drive. At 7:22 p.m. on St. Patrick’s Day, 2005, he called 911 about a “pothole that is blocking [the] road.” Then there was the pile of trash in the road near the local Kohl’s, which he reported on Nov. 8, 2010. “[Complainant] states it appears recently dumped and appears to contain glass,” the dispatcher dutifully reported.

Part of a Powerpoint lesson on neighborhood watch programs by the Sanford, Fla., police department: City of SanfordAt 9:02 p.m. on September 21, 2005, he called 911 about a stray dog on Skyline Drive. At 7:22 p.m. on St. Patrick’s Day, 2005, he called 911 about a “pothole that is blocking [the] road.” Then there was the pile of trash in the road near the local Kohl’s, which he reported on Nov. 8, 2010. “[Complainant] states it appears recently dumped and appears to contain glass,” the dispatcher dutifully reported.

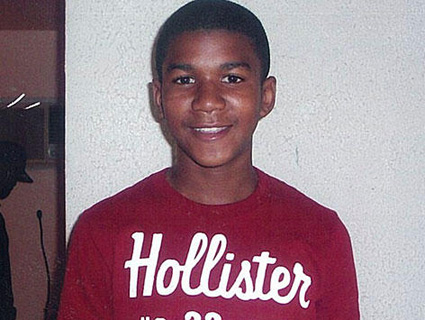

A new 47-page document, quietly dumped online by the city of Sanford, details some of the phone calls George Zimmerman made to emergency dispatchers in Seminole County, Florida. Zimmerman, a self-styled neighborhood watch captain in his Orlando suburb, shot 17-year-old African American Trayvon Martin dead last month after reporting him to police as a suspicious person prowling the area. Zimmerman now claims Martin attacked him on the street, and he defended himself with deadly force.

But the newly released police calls paint Zimmerman as a man obsessed with law and order, with the minutiae of suburban life, and with black males.

Most of the calls seem to cover mundanities: Zimmerman reported a male driving with no headlights; a yellow speedbike popping wheelies on I-4; an aggressive white-and-brown pitbull; an Orange County municipal pickup cutting people off on the road; loud parties; open garage doors; and the antics of an ex-roommate, Josh, that he’d thrown out of their apartment. On September 9, 2009, he called to report another pothole, this one on Greenwood road, advising the dispatcher that “it is deep and can cause damage to vehicles.”

He especially had concerns about kids in the neighborhood. On June 16, 2009, shortly after school had let out for the summer, he called to complain about six to eight youths playing basketball near his development’s clubhouse, “jumping over the fence going into pool area and trashing the bathroom,” according to the dispatcher’s notes. This past January, he called to report five or six children, ages 4 to 11, playing in the neighborhood. The kids, he told a dispatcher, “play in the street and like to run out [in front of] cars.”

But when there weren’t kids or garbage to report, he’d spend his evenings looking for would-be burglars. At 2:38 a.m. on Nov. 4, 2006, he called about a late-model Red Toyota pickup “driving real slow looking at all the [vehicles] in the complex and blasting music from his [vehicle].” It’s not clear if Zimmerman feared the driver was a car thief, though car thieves tend not to blast music through the neighborhood while practicing their craft.

But even more than cars, he was concerned about black men on foot in the neighborhood. In August 2011, he called to report a black male in a tank top and shorts acting suspicious near the development’s back entrance. “[Complainant] believes [subject] is involved in recent S-21s”—break-ins—”in the neighborhood,” the call log states. The suspect, Zimmerman told the dispatcher, fit a recent description given out by law enforcement officers.

Three days later, he called to report two black teens in the same area, for the same reason. “[Juveniles] are the subjs who have been [burglarizing] in this area,” he told the dispatcher.

And last month, on Feb. 2, Zimmerman called to report a suspicious black man in a leather jacket near one of the development’s units. The resident of that townhouse, Zimmerman told dispatch, was a white male. Police stopped by to investigate, but no one was there, and the residence was secure.

After that, there’s one final call logged in the report. At 7:11 on February 26, Zimmerman called police to report a black male in a dark gray hoodie. A few minutes later, that male—Trayvon Martin—lay dead on the sidewalk.