Mark Makela/ZUMA

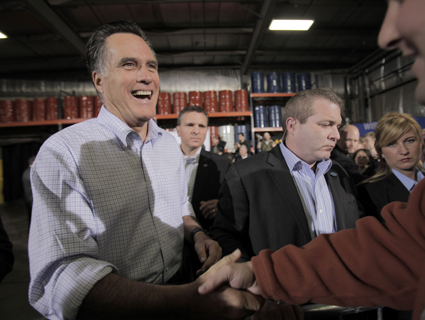

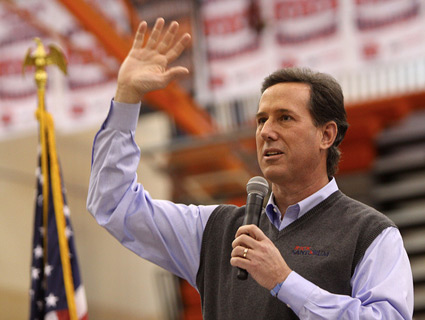

Last week, appearing in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Rick Santorum surrendered to the inevitability of Mitt Romney and suspended his insurgent and quixotic presidential bid. Shortly after that announcement, Santorum held a conference call with several conservative movement leaders. Most of the people on the call had previously encouraged him to stay in the race. But Santorum had told them that the presidential bid was putting a strain on his family. (At a dinner with these folks in March, Santorum complained he had had only five days off since beginning his campaign.) Now, in this post-retreat call, he emphasized that he needed to unwind and focus on his family. The conservative leaders accepted the former Pennsylvania senator’s decision—it was too late to argue, anyway—but there was another matter they did encourage him to consider: his future as a conservative leader. That future could well be shaped by a choice facing Santorum: whether to be a cheerleader for Romney or an ideological enforcer for the right.

Richard Viguerie, a political direct-mail pioneer and a founding father of the modern conservative movement, was one of the right-wingers on that call with Santorum. As he recounts it, this gang encouraged Santorum to use the conservative cred he established during this campaign to establish himself as the preeminent figure on the right: “I specifically said that for the 50 years I’ve been involved in conservative movement politics, we have always needed more organization, more candidates, more money, more think tanks, and more elected officials, but that all of that pales in comparison to one thing: We need above everything else leadership.” And Viguerie was nominating Santorum as the new grand pooh-bah of the right. “There really is no obvious leader for national conservatives,” he says.

“Nobody dissented,” Viguerie recalls. “Everyone is prepared to follow Rick’s leadership.” And one act of leadership these conservatives are looking for Santorum to deliver is an effort to keep Romney from running out on his pledges to the right. “If Romney wants conservatives,” Viguerie insists, “he has to ask for meetings, he has to assure conservatives he’ll keep his promises, and do this with the vice president pick, the platform, the convention speeches, his staff choices. He has to communicate to the grassroots he’s for real and will govern as a conservative. He needs us. We don’t need him, and after he’s spent $100 million trashing Newt Gingrich, Michele Bachmann, Herman Cain, Rick Perry, and Rick Santorum, he has a mountain to climb.”

This is where Santorum comes in. “In dealing with the Romney campaign,” Viguerie says, “it is easier to have one voice than, say, eleven.” He means that if Santorum will be the right’s watchdog, conservatives can be more effective in holding Romney accountable and demanding conservative speakers at the convention, conservative platform planks, and a conservative vice presidential selection. Viguerie defines the most important political battle in the country of the past 100 years not as the never-ending tussle between Democrats and Republicans but as the ongoing clash between “small-government conservatives” and “establishment Republicans,” and he’s angling for Santorum to carry the flag for the former in the tug-of-war with the latter.

But does Santorum want to be this sort of conservative standard bearer and pressure rather than pump up Romney in the months leading up to the November election? The traditional play would be for him to slap on a happy face and jump on the Romney bandwagon. Adopting a less accommodating course of action—say, assuming the role of conservative muscle man—could place Santorum at odds with the Republican establishment, and that could inconvenience him as he plots his future (as a 2016 candidate, lobbyist, TV host, or whatever).

If Romney does trundle toward the middle—as some conservatives fear—Santorum will have, Viguerie notes, “a bigger microphone than the rest of us” to cry foul. “He has the standing to call him out. If not Santorum, who?…He is now the dominant conservative in the nation.”

But should Santorum chose not to use that newly acquired microphone in an ideological muscle-man manner, he could put his standing as the Next Big Thing on the right at risk. And Viguerie is quick to point out that the conservative bench is deep: “There’s a traffic jam of small-government, world-class conservatives who will run in 2016 if Obama wins reelection.” He cites Virginia Attorney General Ken Cuccinelli, Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio, Indiana Rep. Mike Pence, and others.

At the moment, Santorum can seize the would-be-Reagan mantle because, as Viguerie says, “nobody really speaks for conservatives right now.” But, Viguerie adds, the once-tossed-out Pennsylvania senator ought to be hearing footsteps behind him, because of this group of contenders rising in the ranks. Consequently, Santorum could face a dicey time in the coming months, juggling his responsibilities as the prince of the moment on the right and a loyal Republican pledged to support the nominee.

Santorum hasn’t yielded public clues regarding how he views his political destiny. Will he be a good soldier for Romney, or the leader of the forces wary of the one-time moderate Republican? At the NRA’s annual convention in St. Louis on Friday, Santorum did pledge he would “be all in” and “do everything we can” to elect Republicans and conservatives in November. He did not mention Romney by name.